After visiting enough historical railroad stations (or by reading this blog) it doesn’t take too long to get accustomed to the decorative symbols enmeshed within the architecture. A set of symbols, like the caduceus and the winged wheel, are all associated with transportation, and can be found on stations near and far – especially those designed in the Beaux Arts style. Many of these stem from the Roman deity Mercury – the swift messenger god that became associated with transportation, always depicted wearing a winged cap and a with caduceus in hand. Also common is the winged wheel, representative of both Mercury and speed, which has represented transportation beyond railroads. The auto industry has made use of the symbol, and it can even be found in use today as the logo of the Detroit Red Wings. Other symbols, like the eagle, are representations of American patriotism. And for all those New York Central fans, the acorns and oak leaves symbolic of the Vanderbilt clan can be found within the railroad’s most notable stations.

Â

Â

Â

Â

A – Winged cap and caduceus, both symbols of Mercury, god of transportation, New York Central station, Bronxville

B – Winged wheel, transportation and speed, New York Central building

C – Caduceus and horn of plenty, symbol of Mercury, and of prosperity, Michigan Central Station, Detroit

D – Eagle, representing American patriotism, Utica Union Station

E – Acorns, adopted crest of the Vanderbilt family, New York Central station, Yonkers

F – Mercury, Roman god of transportation, Grand Central Terminal

On one Metro-North station, however, you’ll find a particular symbol that isn’t quite common in rail stations – the griffin. Griffins are the mythological hybrid of the lion and the eagle, depicted with a lion’s body and an eagle’s head. Besides being the venerable king of beasts, as the lion was generally regarded as the king of animals and the eagle as the king of birds, the griffin guarded treasure and wealth. Architect Cass Gilbert incorporated the symbol into several of his designs, including New Haven Union Station, and the West Street Building in Manhattan, which was used as an office building by the Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad. Many men amassed fortunes in the railroading business, and these griffins became the symbolic guardians of this wealth.

The West Street Building, now usually called 90 West Street, once towered over lower Manhattan, circa 1912

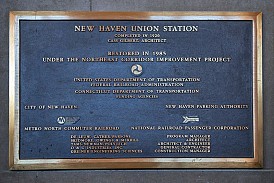

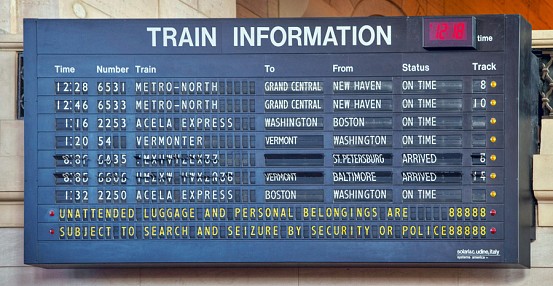

Though Cass Gilbert is usually remembered as the designer of New York City’s first skyscrapers, his elaborate portfolio consisted of museums, state capitol buildings, courts, libraries, and even train stations. Gilbert’s most notable station is New Haven’s Union station, which opened in 1920 and replaced an earlier station destroyed by fire. For a Beaux Arts design, the station’s exterior is really rather plain, but the inner waiting room and ticket windows are undoubtedly beautiful. Over-exaggerated embellishments are few, though observant viewers can spot griffins on the wall in the office section of the station.

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

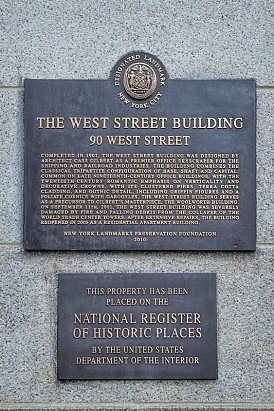

Through a twist of fate, Gilbert’s most notable griffins would be those found on the West Street Building. Completed in 1907, the 23 story building was one of the tallest in lower Manhattan. Over time it became dwarfed by neighboring skyscrapers, and eventually the World Trade Center. Though it was always a gorgeous historical part of New York, the West Street building gained much notoriety after the attacks in September 11th, 2001. The building took major damage – fires lasted for days, and debris rained down on it from the collapsing towers. Two people died in the building’s elevator, and portions of one of the hijacked planes were found on the building’s roof. Ultimately, solid construction won the day – although the damage was immense, the building survived.

90 West Street eventually became dwarfed by the World Trade Center, seen in 1970 during construction and in 1988. Photos by Camilo J. Vergara.

Nearly a hundred years apart – 1907 and 2001

FEMA photo showing the damage and debris pile below 90 West Street on September 21st. Photo by Michael Rieger.

90 West Street was eventually restored, and reopened as a residential building. It now contains 410 separate apartments, ranging from studios to three bedroom units. Countless embellishments inside and out were destroyed, though many were recreated using old photographs. Many of the gargoyles on the outside are modern creations in the style of the originals. One of the original surviving griffins, however, can be found in the lobby of the building. He’s no longer guarding the wealth of railroads, though I suppose one could say he is now guarding the wealth of the well-to-do tenants of the building – studios start at about $2250 a month.

Love your tours!

Always with wonderful photos.

Thanks.

Dennis