For most people of my generation, the letters YMCA evoke an image of the Village People – far removed from the Young Men’s Christian Association it was founded as. Just as likely, one does not picture a group long associated with railroading, and certainly not an establishment designed by the likes of vaunted architects Warren and Wetmore. In reality, all of these statements are true – the YMCA was first established in New York in 1852, and a Grand Central Branch (also known as the Railroad Branch) was formed in 1875. Meeting in the basement of the Grand Central Depot, the fledgling organization was a second home to railroad men, and Sunday bible studies were led by Cornelius Vanderbilt II himself.

The YMCA organization was founded in 1844, but first became involved in the lives of railroaders in 1872 in Cleveland, Ohio. Besides the obvious religious aspect of the organization, it became a home where railroaders could be welcomed among colleagues and friends. Sermons and Bible studies, as well as decent places for railroad men to rest, get a meal at any hour, or diversions to pass the time, could all be found within the YMCA’s doors.

Â

Â

Â

Â

Typical scenes at YMCAs of the era. The first row depicts the 23rd Street YMCA in New York from the Library of Congress. Second row shows the Railroad YMCA in Washington DC by Herbert A French.

As Grand Central Terminal’s centennial year draws to a close, there are two more buildings designed by Grand Central’s architects that I wish to mention – one of which was the home for the Grand Central YMCA for fifteen years. In case you missed the previous entries in this series, you can check them out here:

Warren & Wetmore:

The New York Central Building

Yonkers Station

White Plains and Hartsdale stations

Reed & Stem:

Glenwood Power Station

Stem & Fellheimer:

Utica station

The entire Grand Central Terminal complex, as envisioned by the New York Central Railroad’s Chief Engineer William Wilgus, was more than just a simple train station – it was a “Terminal City.” Hotels and other such amenities were built for the convenience of travelers, and the magnificent New York Central Building became the new home of the railroad’s management. One rarely mentioned feature of the Terminal City was intended to serve the basic railroad worker, and provided amenities to those that worked long hours to get people where they needed to go by train. Although the building was short lived, the Grand Central, or Railroad Branch, of the New York YMCA formed an inextricable piece of the fabric that is Grand Central, and the lives of those that toiled within.

The old YMCA (at left), and some members outside the new YMCA (at right).

Steadily rising from the modest organization it was founded as in a train station basement, the New York Railroad Branch of the Young Men’s Christian Association found its own home at the corner of Madison Avenue and 45th Street in 1886, whose capacity was doubled in 1893. By 1902 the Railroad Branch YMCA was celebrating its 26th anniversary as one of 170 local railroad branches in the US and Canada, all of which had a membership of more than 43,000. New York alone had 31 branches, and nearly 10,500 members. Plans for the new Terminal City, and this increasing membership, necessitated a new home again in 1912. Three Vanderbilts – William Kissam, Frederick, and Alfred Gwynne – each donated $100,000 for the establishment of a new seven-floor building at Park Avenue from 49th to 50th streets which perfectly fit with the aesthetic of the new Terminal City.

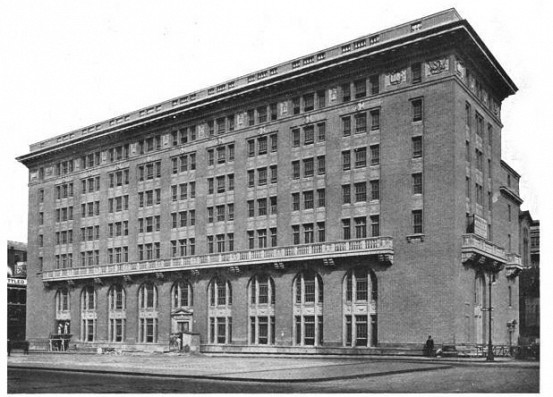

The new New York Railroad Branch YMCA

Opened in 1914, the new YMCA building was a fairly modest affair of cream colored pressed brick and Indiana limestone trim, 200 by 47 feet. Typical of the work of Warren and Wetmore, the building featured various fine detail work including the flying wheel – representative of transportation and the Roman god Mercury – an open bible marked with the symbols for Alpha and Omega, the lamp of knowledge, and a YMCA emblem. Leadership of the YMCA described the building as both dignified and attractive, and although fitting with the Terminal City, it was an easily distinguished building with its own individuality.

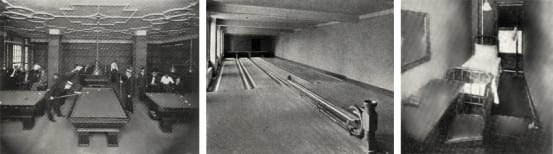

Members and guests of the YMCA had a wide options of amenities open to them. For those looking to socialize, the inside of the new YMCA featured a spacious lobby designed for such purpose – one could a piano and a fireplace to sit around. Warren and Wetmore detail work could equally be found inside the building, and engraved on the marble above the fireplace were the choice words “Sprit, Mind, Body,” a motto of the YMCA. Those looking to write letters home or catch up on news could find the requisite items in the Correspondence Room, while those looking for a little fun could find it on the six billiard tables also found on this floor. Finishing off the first floor was a checkroom for baggage and uniforms, lavatories, and a full service barber shop.

The lobby and bathroom found on the first floor.

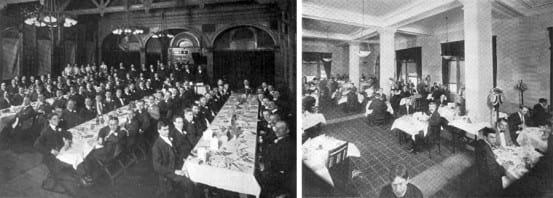

No matter what hours a man worked, a restaurant and kitchen was open at all hours to serve, which occupied the entire second floor of the building. It featured the most elaborate restaurant of any YMCA at the time, with three dining rooms and seating for a total of 320 people. Meals ranging from ten to fifty cents were offered here, and lunches for thirty cents were offered in the popular Club Lunch Room.

Those that would opt for exercise could find a 40 x 75 foot gym, two full floors in height, on the third floor, complete with a spectator gallery for 100 people. The gym could be converted for use as an auditorium which could seat 500, and a stage and dressing room was available for this purpose. Four of the most modern Brunswick bowling alleys, featuring rubber “Mineralite” bowling balls were also located on this floor. A darkroom for the camera club, and a library with three reading alcoves could also be found on the third floor. Alfred Gwynne Vanderbilt took on the responsibility of keeping the library stocked with the newest and most desirable books, at times donating up to a hundred new volumes per month. YMCA members could borrow two books at a time for a two week period.

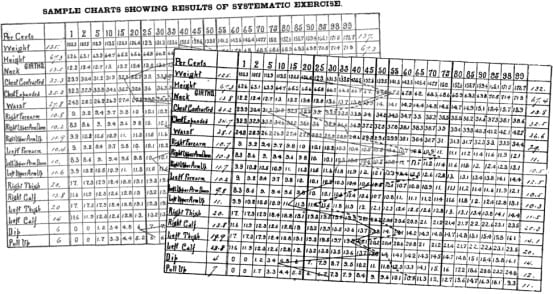

Tracking the health of railroad men – the YMCA was a place to expand one’s spirit, mind, and body.

A locker room for the gym could be found on the fourth floor, as well as a lecture room with space for 125. Various classes were offered, from railroad-related Air Brake classes to First Aid, Public Speaking, and even Investing classes. For those on long swing shifts or long distance journeys that required rest, both single and double rooms were available in increments of 12 hours. These rooms occupied the fifth through seventh floors of the building. Several rooms were located on the fourth floor, but the majority took up the fifth, sixth, and seventh floors. Rooms averaged six by seventeen feet in size, and all had outside windows. At roof level one would find a canopied summer garden, seasonal courts for handball and tennis, and room for meetings during good weather.

Despite the featured amenities, the YMCA outgrew the building in a mere fifteen years, and the Warren and Wetmore construction was demolished. These days the Railroad Branch of the YMCA still exists, although it is referred to as the Vanderbilt Branch, in honor of Cornelius Vanderbilt II, the man that invested considerable time, effort, and money in the organization, back when it met in a lowly basement of Grand Central Depot. The exclusive male membership and religious aspects of the YMCA have been supplanted with a focus on community and opportunities for all. The organization has even distanced itself from its long standing acronym and has attempted to rebrand itself as merely “The Y.” Few ties to the railroad remain, besides the Vanderbilt name, and its proximity to Grand Central Terminal.

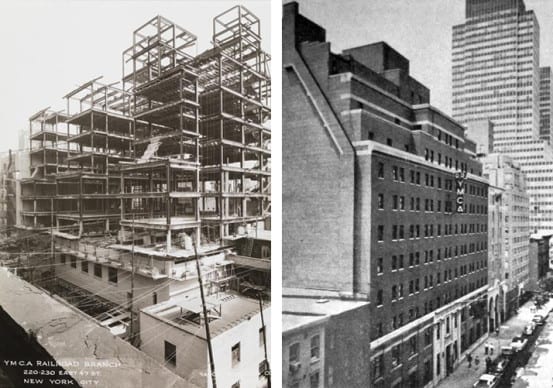

The YMCA that replaced the Warren and Wetmore building, which still exists today. Construction photo at left from the Museum of the City of New York.

Some of the amenities offered to railroaders at the YMCA are still required to this day. Though definitely not as nice as the elaborate setup of the original YMCA Railroad Branch, locker rooms and bunk rooms for those with long train jobs to sleep can be found today in Grand Central. The upper floors of Grand Central hosted these for many years, though they shared one thing with the original YMCA – they were for men. Exclusive facilities for women didn’t exist all the way up through the Conrail years, but were finally established in the early ’80s. In the mid to late ’80s the bunk and locker rooms were relocated to the dark recess known as Carey’s Hole, and were relocated again to the third floor last year. In the lounge you can likely find conductors and engineers passing their free time playing cards, much as they did at the Railroad Branch.

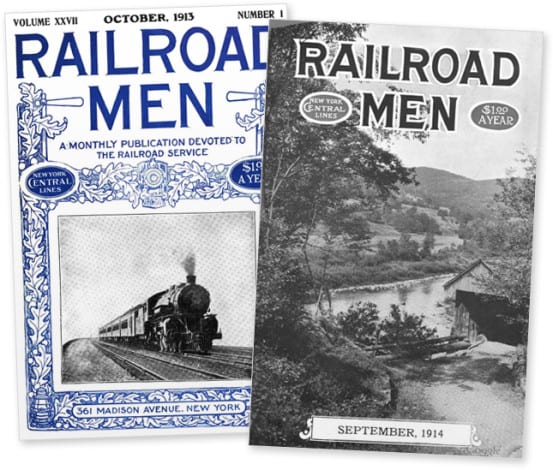

The publication Railroad Men was printed by the Railroad Branch of the YMCA in New York. Note the design at left featuring the oak and acorn motif which appears frequently in Grand Central, symbols of the Vanderbilt family.

In 1973 I bought a Greyhound “AmeriPass” and set out to see the USA. My plan was to save money by traveling at night and sightseeing by day but every once in awhile I needed a break from that routine. At the time you could still rent a room at some of the urban “Y”s and I did so in New Orleans and Seattle. When my trip ended in San Francisco I checked into the “Y” there (on the corner of Turk and Hyde) and stayed for about a month until I joined the California Ecology Corps and moved out to Camp Parks in the East Bay area. I remember that, at the SF “Y”, you’d leave your key at the front desk when you went out so visitors could be told that you were out. There was also a large lounge with a row of typewriters (presumably so you could write letters home). It sounds so “ancient” but, in my life, it doesn’t seem that long ago.