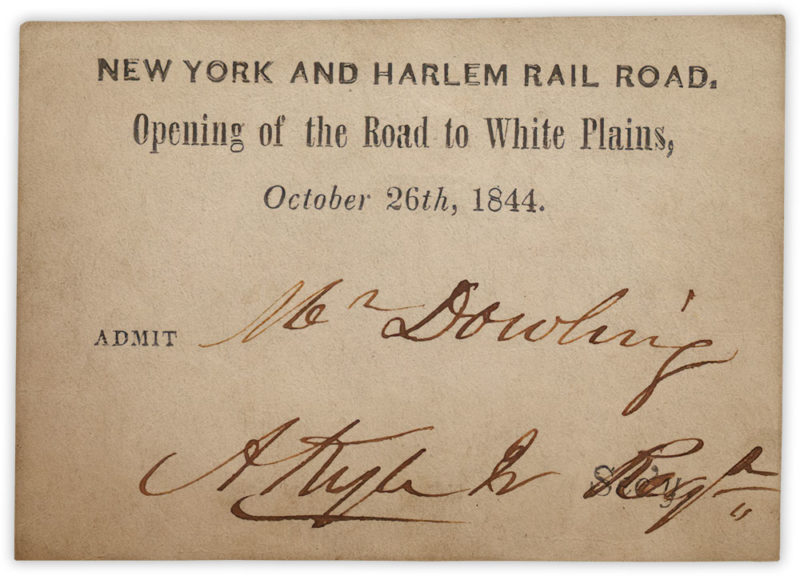

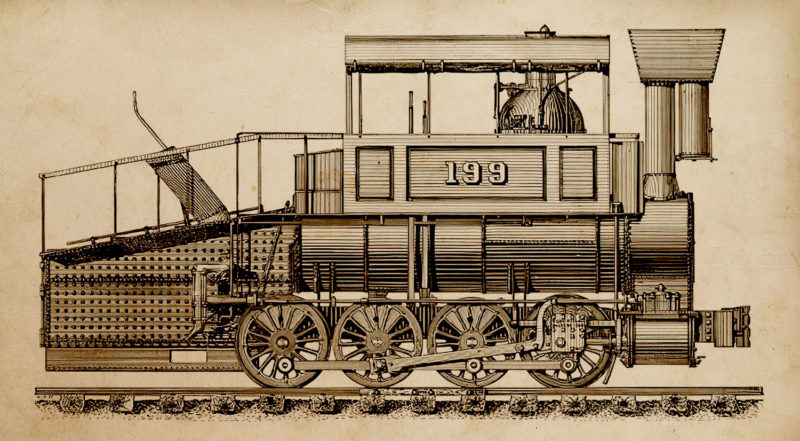

Amid loud booms of celebratory artillery fire and the rousing tunes of a brass band, hundreds of onlookers jockeyed for a spot alongside gleaming rails, cheering and popping champagne corks. The crowd’s cries rose to a crescendo as the mighty iron horse cantered round the last curve and roared into full view, steam billowing behind her. The day was Saturday, October 26th, 1844, and at long last—thirteen years for the rails, nearly three hours for the train—the New York and Harlem Railroad had reached White Plains.

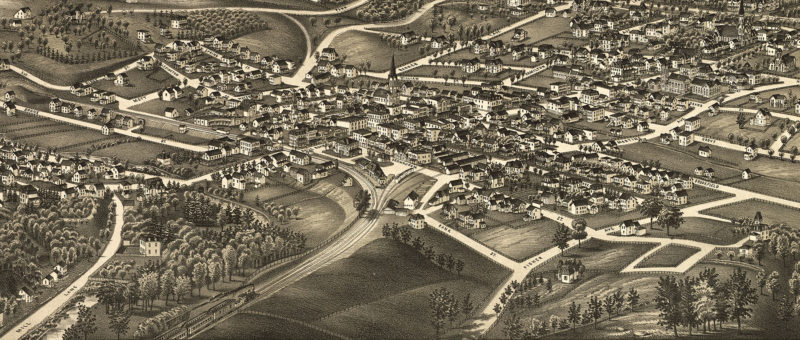

The new station to which the train had arrived was a simple wooden affair, which the guests likened to a “barn-like shanty.” It simply blended in with the rest of the small farming town of just over a thousand inhabitants. At the time White Plains was merely a “sweet inland village” just over the “pleasant hills and through the valley of the Bronx.” It was remembered as a battlefield of the Revolution, and where George Washington kept his headquarters for a time. But now, linked with rails of iron (and they were iron—not the metal-strapped wood rails the Harlem had spent much money to experiment with and later replace) to the city of New York, surely this sleepy town was bound to grow exponentially!

Adding to the crowd already surrounding the station, the three hundred or so railroad brass and their invited guests ambled out and onto dinner just a short ways away. Their trip began at New York’s City Hall, stuffed until they were practically overflowing into cars hauled by horses of the flesh and blood variety. Transferring over to a steamer at 27th Street they began their journey of “romantic and historical tradition and reminiscence†which is just a fancy way of saying that when the president of the railroad is on board and wants to stop to fill up on alcohol, by God you stop the train at Harlem and Fordham to get more, of course!

Thankfully railroad president David Banks was not too inebriated to provide a rousing speech highlighting the Harlem’s past obstacles and opposition overcome, and provide optimism for the future of the railroad—North to the Housatonic? West to Albany? Something great surely would be happening forthwith as it was the manifest destiny of the capitalists and businessmen of New York to build a railroad to Lake Erie and then the west!

And one cannot forget the toasts!

To the Judiciary of New York—their learning and judgement—as well as the ladies, of whom we see many here—how can the Harlem Railroad fail to prosper, supported by law, love, and physic?

To the farmers of Westchester County, may they reap the benefit of riding on a rail!

Those were, of course, two of many mentioned that night. As far as reaping benefits, it was not only the farmers of Westchester that would be advantaged, but likewise many of the men that celebrated that evening… and the residents of a tiny village that would eventually grow to become the city we know today.

Although there was a good road—thank the sticks and stones, and iron, and other hard materials, including the hard-fisted laborers who worked on it; although there was good weather—thank God—it requires the whole of these commendable considerations together to reconcile one to a dreary, monotonous kill time journey of 3 hour’s duration on 23 miles of a railroad.

—An unfortunately sober reporter for the New York Herald

These [the Harlem Railroad and New York ferries] being cheap and public modes of conveyance, are crowded with masses of people escaping from the city, and pouring themselves out upon the places in its immediate vicinity. The influence arising from this evil is most deleterious. It allures the population from the sanctuary to scenes of mirth and sin. It inflicts on the inhabitants of these adjacent localities, the curse of a vicious and reckless influx of strangers. Intemperance, licentiousness, profaneness, and every form of irreligion, are thus fostered, both in the city itself and in the places of resort around it.

—New York Evangelist rails against the sinful methods of public transportation which operated every day of the week, ignoring the Sabbath, in 1842.

The true measure of distance, especially from a historical perspective, cannot be accurately gauged in miles, but instead in the duration of time it takes one to get there. With the advent of railways, people and goods were able to travel much further than they ever were before, in far less time. But any technological advance of such magnitude inevitably draws out the naysayers, fearmongers, and conspiracy theorists…

The railroad is unnatural! It is sinful! Men were never intended to move at such great speed. Women! Their ovaries will fall from their wombs, rendering them sterile. The jarring motion of the locomotive will make your blood boil, and cause permanent injury to your brain! Madness will certainly be induced by the speed of the dastardly beast! People will surely suffocate! And the cows! Think of the farm animals that will cease to graze, disturbed by this unholy contraption! Hens will quit laying eggs, birds will plummet from the sky in the throes of death.

All of these, and many other, nonsensical beliefs were attributed to the coming of railroads; when preparing their road’s extension, the directors of the Harlem almost expected to hear some of these senseless ideas from the commoners of Westchester.

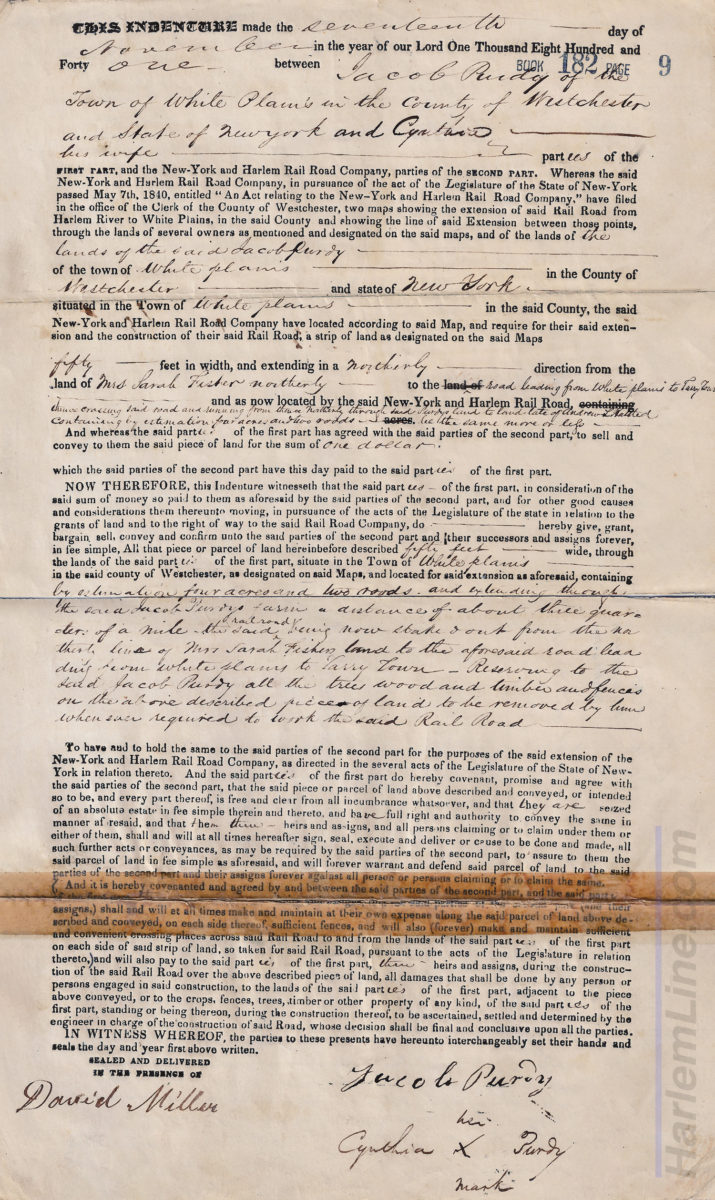

While no protest would stop the expansion of the Harlem, the cooperation of a succession of land owners along the proposed route of the road was needed. Thus the “diplomatic” and “amiable” Gouverneur Morris Jr. was sent out to negotiate, or “overcome the minds of many of the land owners’ existing prejudices against railroads.” In some cases, little fighting was necessary, as residents intuited the value of having a railroad nearby. Two members of the Purdy family fell into this camp— Jacob, who transferred the land for White Plains, and Isaac, whose land later became the aptly named Purdy’s station. In both cases the land transfers were for nominal fees of a single dollar.

Once the land was acquired, construction steadily moved forward. Many of the laborers constructing the road were Irish immigrants, paid up to 75 cents a day and their board—dirt floor hemlock shanties along the future right-of-way. By June of 1844 service to Tuckahoe was open to the public, and the next six miles into White Plains soon thereafter. The openings were well attended curiosities, and for some it was the first time in their life they had ever glimpsed the magnificent iron horse.

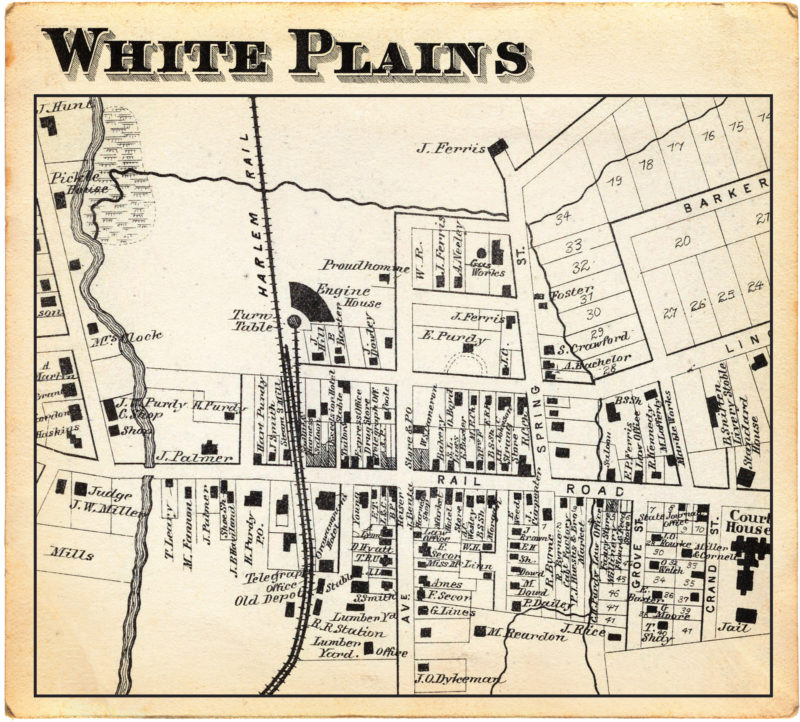

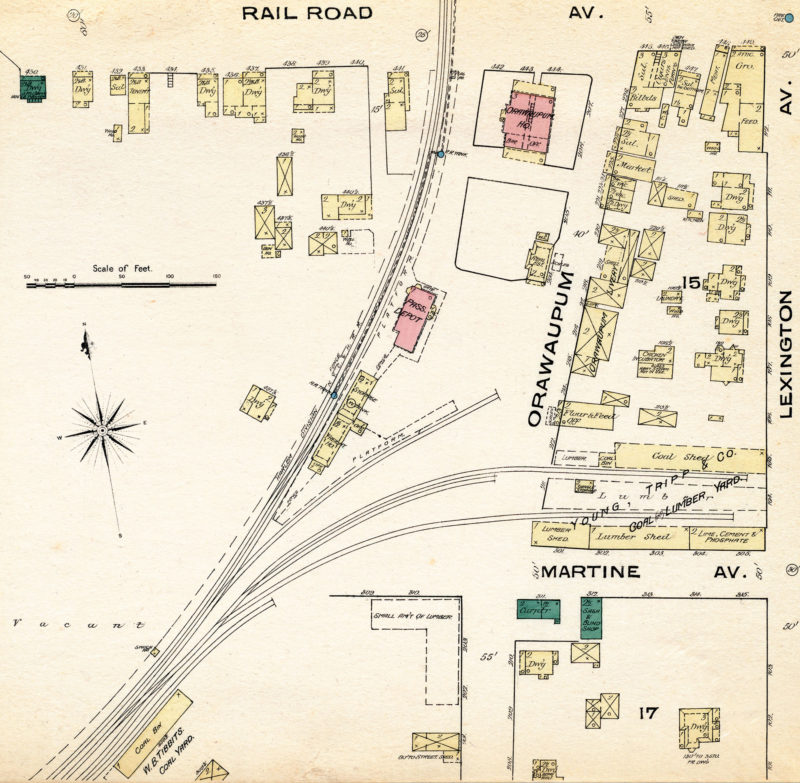

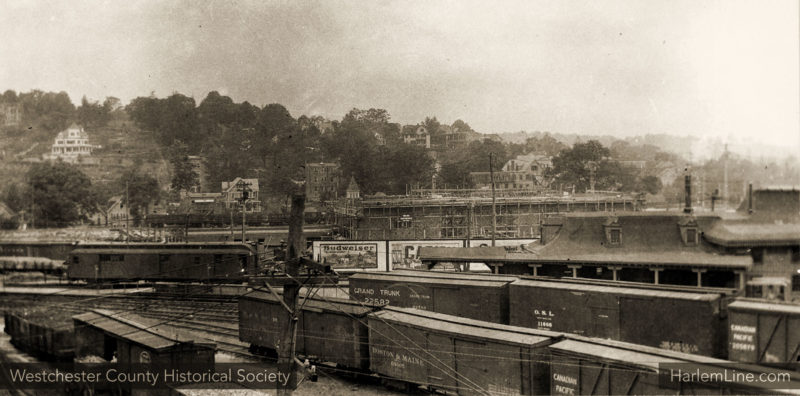

For two full years White Plains served as the terminus of the Harlem Railroad. As such, the road required all the necessary infrastructure to operate, including a roundhouse and turntable. Two small railyards existed on either side of Railroad Avenue (today’s Main Street), with the one on the north end having the turntable, roughly located where the current White Plains station is today. On the south end there were several tracks that directly served some of the new industries that had popped up adjacent to the railroad, including animal feeds, coal, lumber, and other building materials.

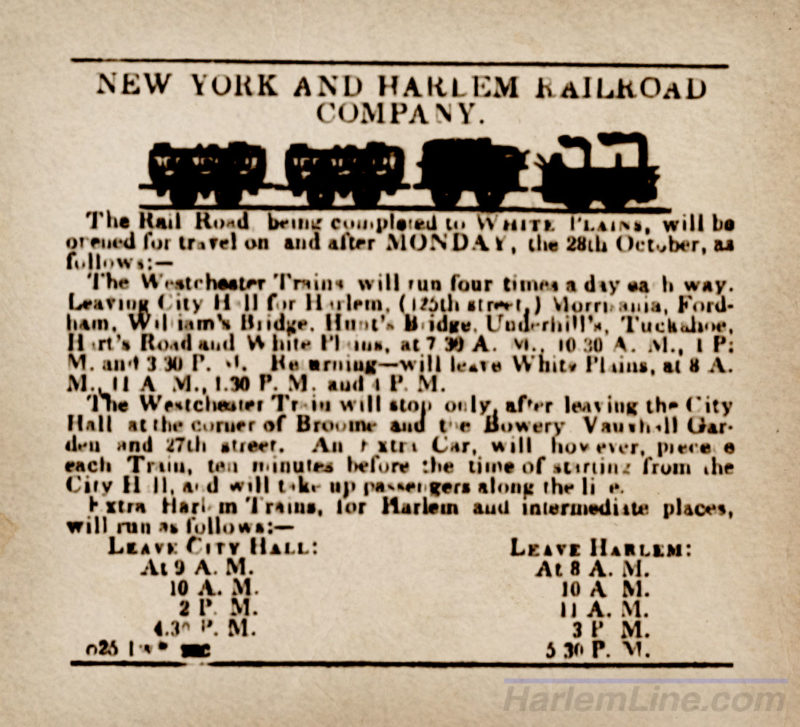

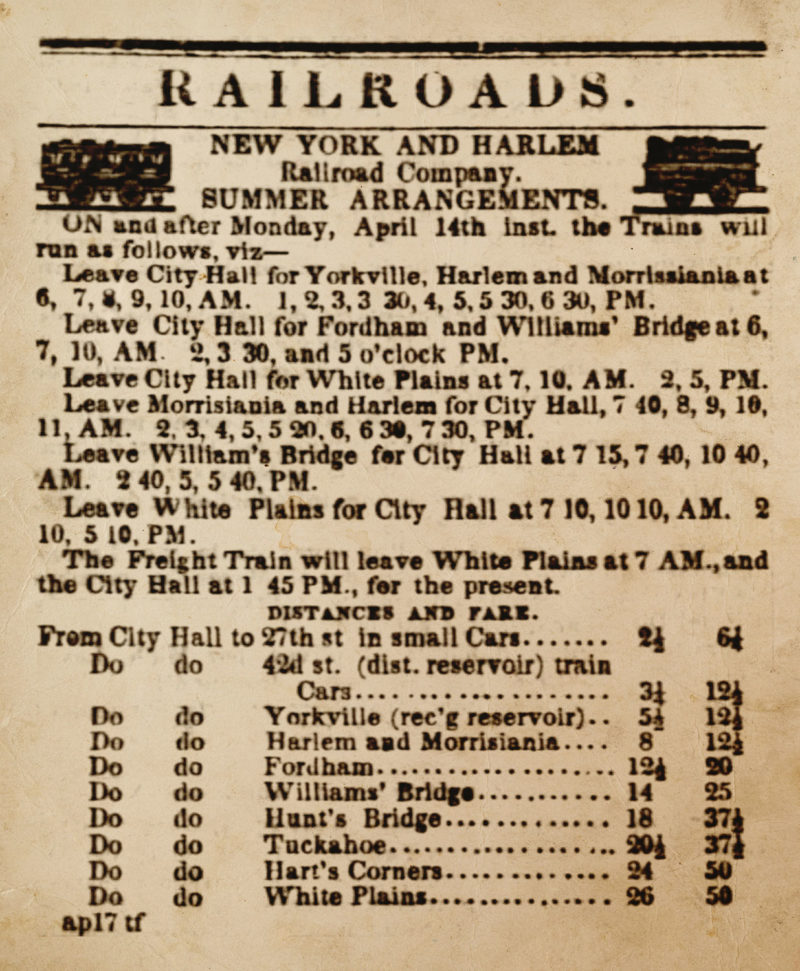

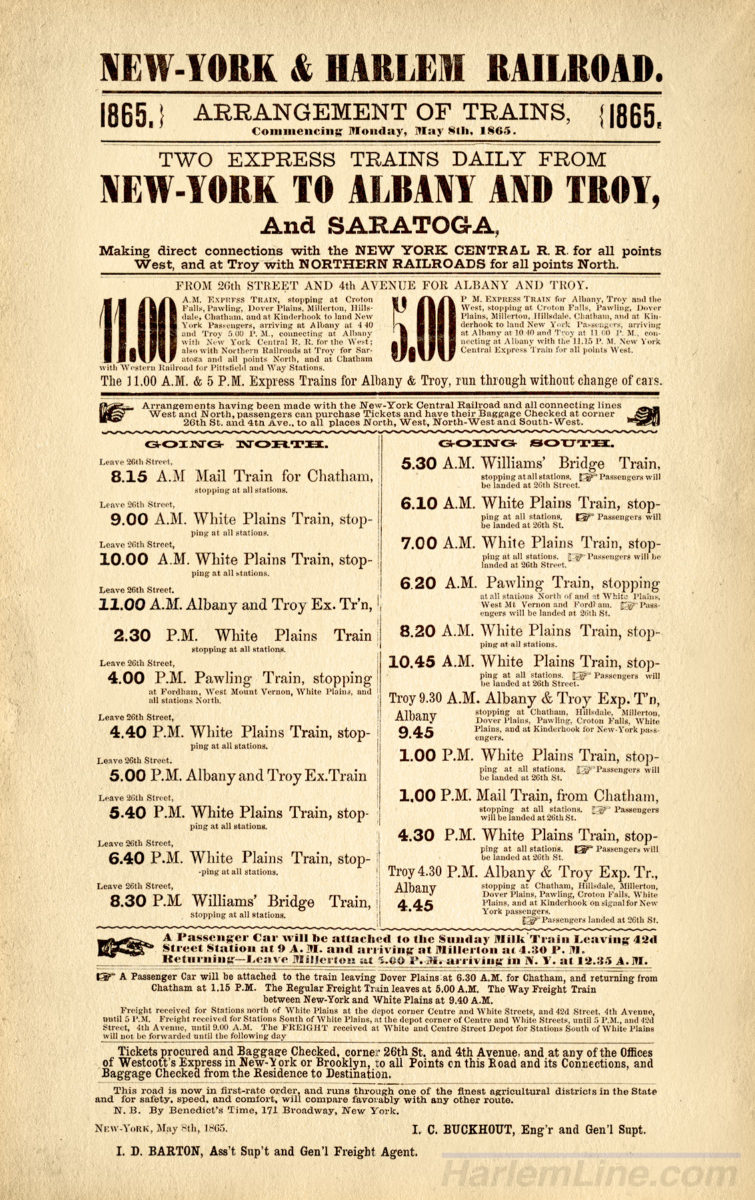

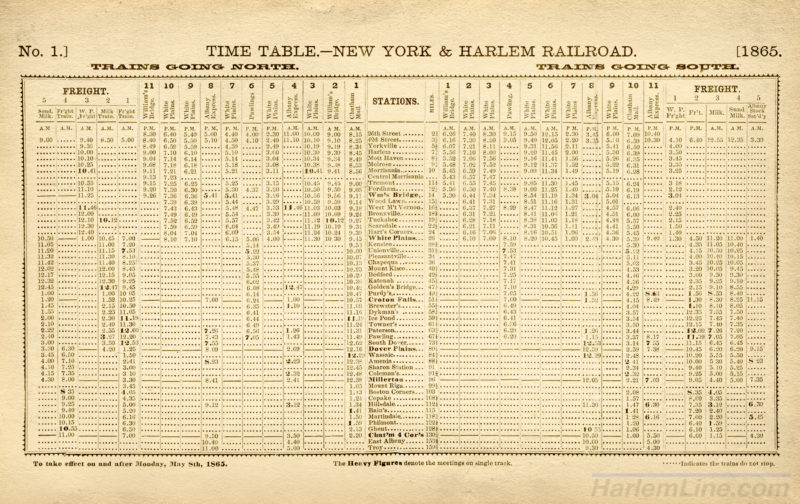

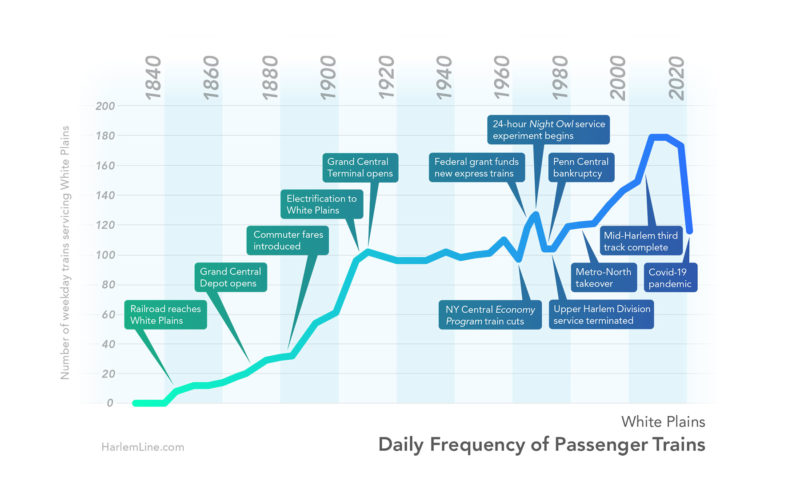

Although industries may have found the rails useful, the population of White Plains did not immediately explode after the coming of the Harlem. The added connectivity was certainly valuable, it was just not frequent—service began with only four round trip passenger trains per day, with the trip taking well over an hour (even without the pit stops for acquiring more alcohol). Over time the frequency of trains steadily increased, and the ride time shortened, thanks to new technology (including electrification) and newly scheduled express trains. And instead of a single flat fare for every trip, new types of tickets were introduced, including booklets intended for commuters with 150 ride coupons, valid for three months from the date of purchase.

Just before the turn of the century the Harlem’s single train schedule was split out into two—Form 112, which included the more distant locations along the Harlem, and the Form 113, which were the commutation trains from Grand Central. The timetables also were broken down into weekday and weekend schedules, with additional southbound frequency in the mornings, and northbound in the evenings, new offerings tailored to the commuter. Finally, White Plains had become a realistic suburb, where both living in “the country” and working in the city was feasible, or as New York Times noted in 1927, “White Plains is but thirty-six minutes from Grand Central Station [sic] and actually nearer in point of time than many subway terminals in New York City.”

The present [railroad] service is the result of a steady and satisfactory growth from year to year, until, at the present time, about as many trains are run during the rush hours of the day as the present track accommodations will take care of… for years the service given has actually exceeded the bare necessities of the business to be taken care of, and that instead of being a little behind the times with its service, the railroad company has led the procession…

In addition to all its other charms as a suburban home center, the village of White Plains has that most indispensable feature of suburban life, a first-class train service; and in this respect it is excelled by no other village in the outlying districts of the center of the universe commonly called New York… If the recent growth of both the village and the train service is any indication, White Plains has a very gratifying future indeed.

—John Rosch’s Picturesque White Plains, 1906.

Looking back over the past hundred-plus years of White Plains’ history, did the city live up to the hopes of Rosch and other citizens of yesteryear? Beyond the railroad, what other factors influenced the growth of this city? How did the railroad, complete with two railyards, come to the state it is now? What transit-oriented development can today’s citizens hope to see in the next decade? All of these questions will be considered in the upcoming continuation of our series on the history of White Plains… coming soon!

Hi, I found this post fascinating, especially the part about the turntable. A former Harlem Line commuter, it never ceased to amaze (and anger) me when our train would pull out from the station until the last car was about an inch from the platform. It would stop, and we’ hear an announcement about track issues or some other issue resulting in delay. Morning commutes were fun as I’d meet the same people standing in the same places on the platform. We’d chat a bit, maybe continue talking in the train, then go about our ways once we arrived at GCT.

Thanks for visiting, and for the comment! It’s been a long time since I’ve regularly commuted from White Plains too… I gave up taking the train every day about six years ago when I managed to snag a work from home job way back when. Your observation about people standing at the same place on the platform makes me chuckle. We’re all such creatures of habit! A little part of me misses seeing the same people waiting every day.

Great article on the New York Central Railroad in White Plains, NY. I especially enjoyed the historical pictures. Anyone including yourself that is interested in the history of the Harlem Division should pick up a copy of a book by Louis V. Grogan titled:

The Coming of the New York and Harlem Railroad.