In Part I of our history of White Plains, we took a look at the arrival of the New York and Harlem Railroad, and how its vital link to New York City kicked off White Plains’ growth from a sleepy little village into one of Westchester’s notable cities. Along that journey a monumental train station rose and fell, man asserted its dominance over nature, and several swaths of civilization were wiped from the map, all in the name of progress.

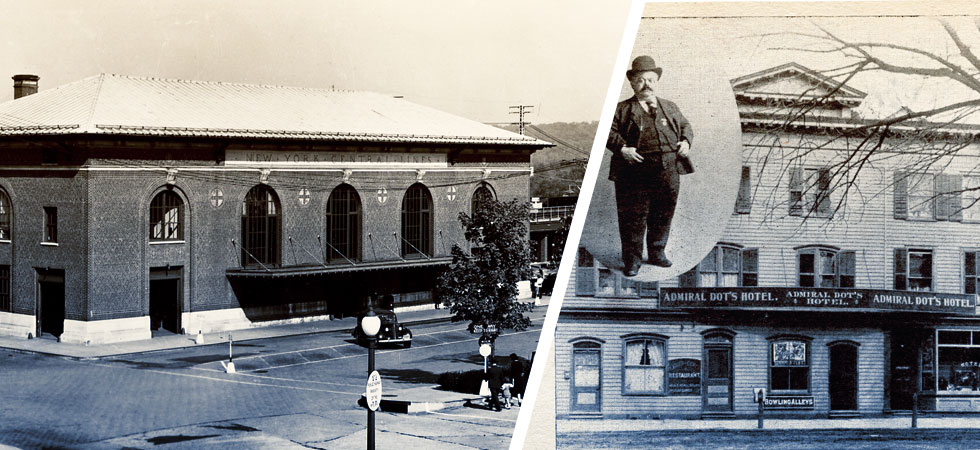

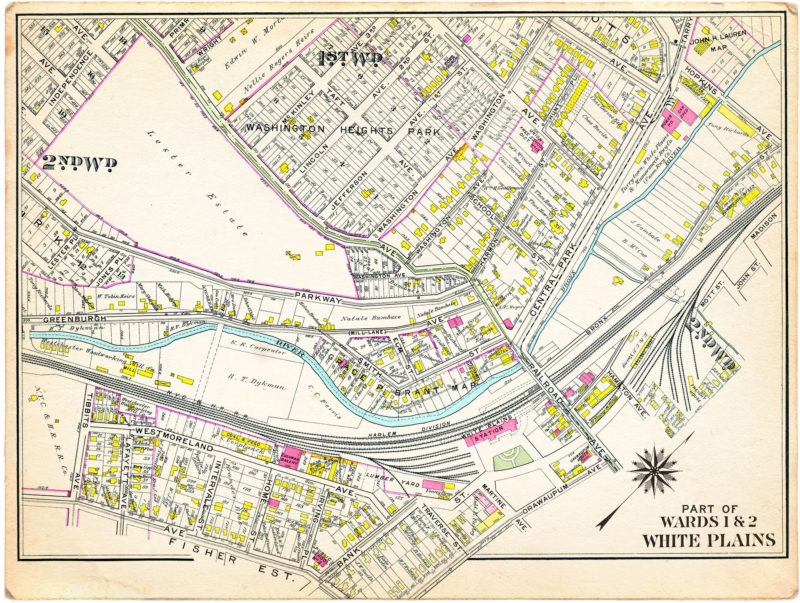

The transformation of the area around the train station in the early twentieth century was quick, and massive. The railroad’s tracks rose up, removing them from grade and separating them from the ever increasing amount of automobiles. The electrification process began, laying under-running third rail to permit electric powered trains which were able to operate more frequently. Meanwhile, older, now-obsolete infrastructure like the turntable north of Railroad Avenue disappeared. And in the area surrounding the station, businesses came and went—some by fire, and others by the wrecking ball.

1910 map showing the railroad’s route through White Plains. The small yard at the south end had disappeared before 1960, and the one at the north end was gone in the late 1960s. This land would become the site of the current station in White Plains.

Enter Admiral Dot

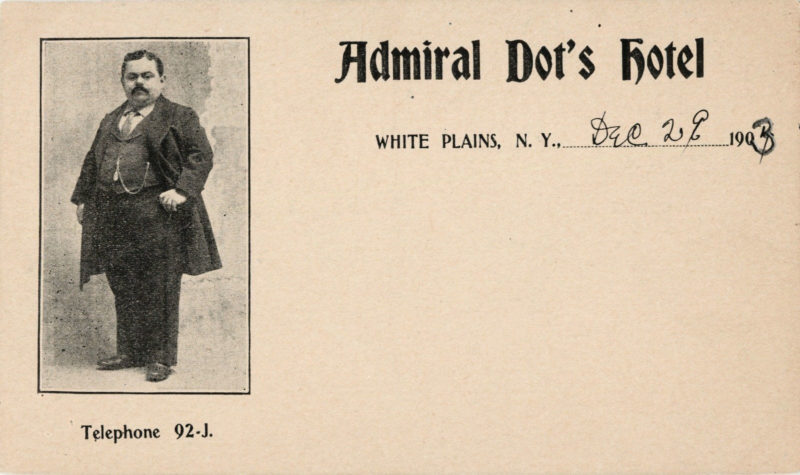

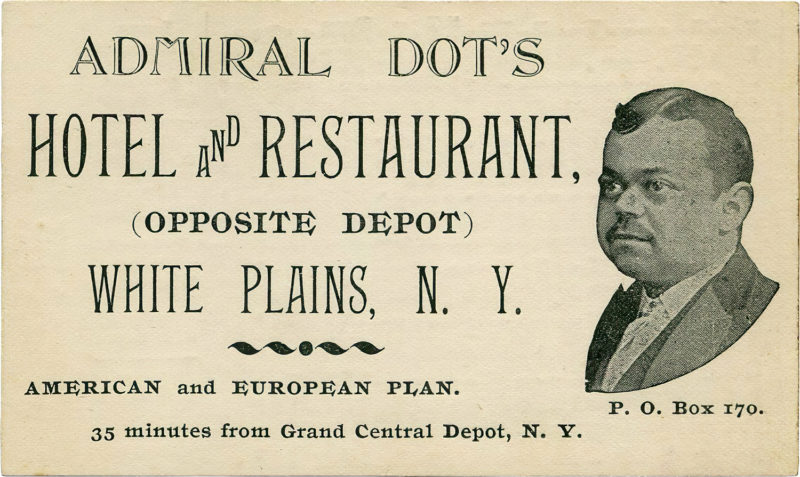

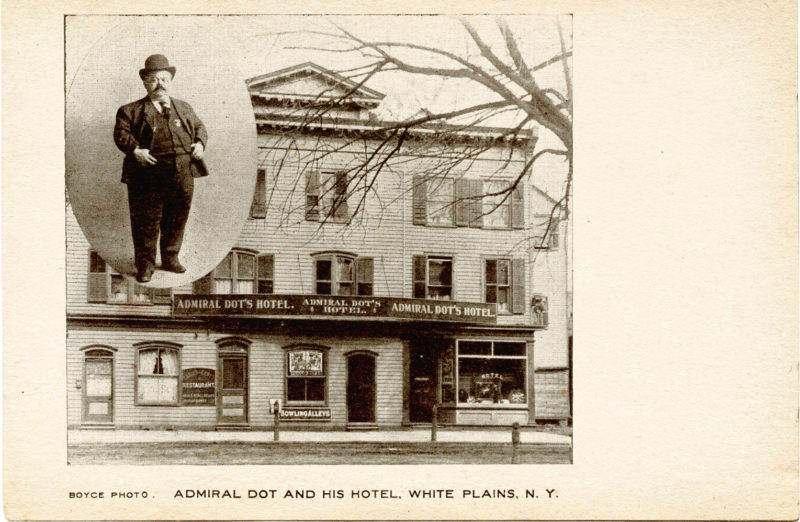

No prominent railroad town would be complete without an array of hotels for weary travelers to lay their heads. Surrounding the depot at White Plains were several, including the Union, the Orawaupum, as well as Admiral Dot’s Hotel.

Owner and operator Leopold Kahn was a quasi-celebrity, previously exhibited as a circus oddity along with several other “midgets” with similar military-esque monikers. The Admiral Dot appellation was given to Kahn in his youth by showman P.T. Barnum himself. Although from a modern lens such “freak show” exhibitions seem ethically problematic, at the time displaying such abnormalities for amusement and profit were commonplace. Dot, who at age seventeen was said to only weigh twenty pounds and was just over two feet tall, was shown alongside “Siamese twins“, a horned woman, and a “man monkey,” among many others.

Though many came simply to gawk at someone they found strange, Kahn actually enjoyed performing, and would sing, dance, and play musical instruments. Outside of the circus he performed as part of an acting troupe comprised of others with dwarfism, where he met his wife Lottie. Soon after their wedding in 1892, Kahn retired from “showbusiness” and took the small fortune accumulated from the circus (a quarter million dollars, equivalent to almost $7.5 million today) to settle down and open a hotel along Orawaupum Street.

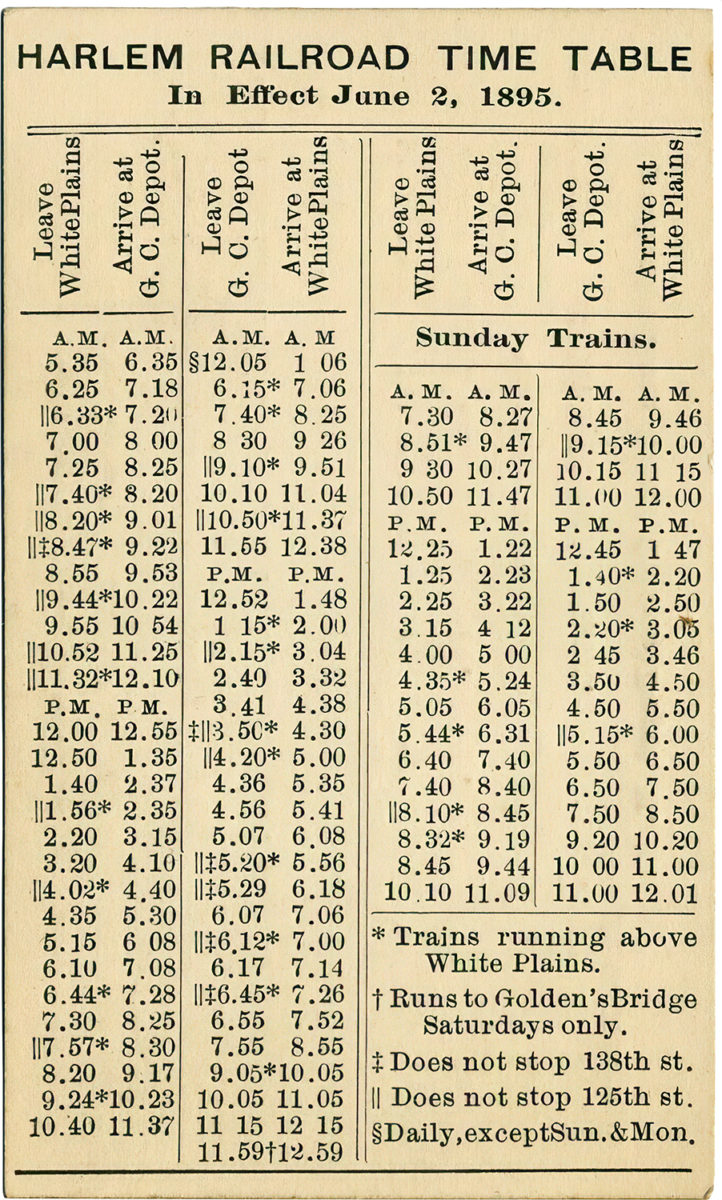

Admiral Dot’s Hotel was just a short walk from the train depot, and even advertised by printing unofficial railroad timetables. A family affair, the couple maintained the hotel with nephew Major Atom (who was also in the circus), who worked as the night clerk. Along with the hotel, which was comprised of 48 guestrooms, a bowling alley, ballroom, and restaurant, Kahn also operated Lexington Hall, a banquet hall and concert venue behind the hotel where the Excelsior Orchestra performed every Wednesday night for dancing. Both survived until February 1911 when they burned to the ground in a fire along Orawaupum Street. As a firefighter with Independent Engine Company #2 Kahn was one of many that fought the fire, but was unable to stop it from destroying several businesses, including his own.

A New Rail Station Rises

Befitting the ever growing city of White Plains, a new monumental station was planned to replace the old, and completed in 1914. Designed by two of Grand Central’s architects, Warren and Wetmore, the station was one of the most notable along the Harlem Line, and a twin to the station built at Poughkeepsie. It boasted a large waiting room (the largest in Westchester County) with six long, double-sided chestnut wood benches, a cafeteria where travelers could grab a meal, and an adjoining room for Railway Express. The new station was built on a pile foundation and featured a copper roof and exterior walls of patterned brick, adorned with terra cotta detailing. The inside was finished with brick and wood paneling, and used steam heating and as expected for a recently electrified railroad, electric lights. Similar to those found in Grand Central, chandeliers featured exposed bulbs, highlighting the use of electricity. Coupled with the large eastern-facing arched windows, the station was filled with light.

The station itself was at street level, but was connected to the raised tracks twenty-five feet above, with 600-foot-long wooden platforms and shelters available for riders to wait.

Despite the sturdy brick construction, the station lasted only 69 years, meeting the wrecking ball in 1983, finally killing off a decayed and graffitied shadow of its former self.

The Bronx River Parkway is Born

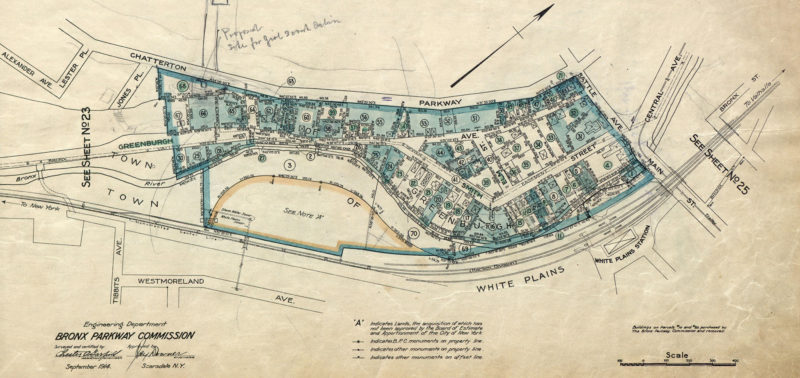

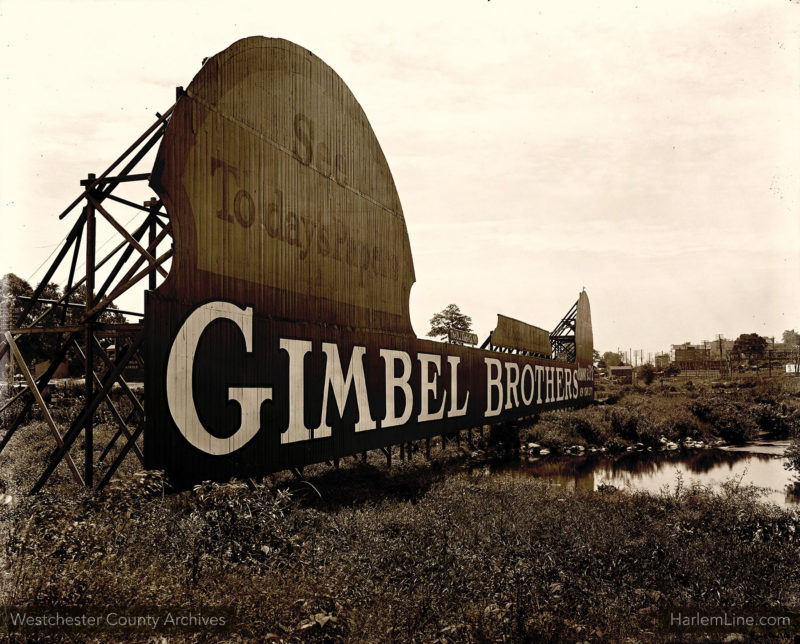

Years of factory waste and the direct dumping of sewage left the Bronx River a foul and polluted waterway, deemed a “serious menace to public health.” The Bronx River Parkway Reservation project, which began in 1906, had several major goals, prime among them to clean up the river and to create a modern and efficient roadway from which to enjoy the scenery. As the railroad paralleled the river in many areas, the restored vistas would be visible to those onboard trains as well. In fact, some of the perceived pollution were the miles of billboards erected on the banks of the river and facing the tracks, advertising directly to the captive audience of train riders.

Although the restoration of the river was an admirable goal, not everyone was thrilled with the idea of the project. Significant portions of land needed to be taken—about two thirds of property owners sold their land directly, the rest was claimed through the courts and condemnation proceedings. Project designers stated that much of the land was blighted and filled with dilapidated shacks that were better off removed, but in reality this wasn’t always the case. In White Plains a neighborhood of Italian Americans on the opposite side of the railroad tracks was ousted, with homes, businesses, and churches razed.

At completion, the reservation was approximately fifteen miles long, and varied in width from 300 to 1,000 feet, with 125 acres in the city and 900 in Westchester.

When looking back at the project through the lens of modernity, I think one can see that cleaning and preserving the river was a necessity. However, the final arbiters of what land was taken and what neighborhoods were razed seemed to have made exceptions based upon cronyism, or to benefit more affluent areas like Bronxville, and likewise introduced ethical issues. Eugenicist and “scientific racist” Madison Grant, leader of the Bronx River Parkway Commission, was likely overjoyed to wipe immigrant neighborhoods off the face of the map, as he saw “non-Nordics” such as Irish and Italians as inferior humans and corruptors of American society.

The Commision’s idyllic vision for the parkway did not include the heavy industry that had grown up around the railroad, and several ousted businesses did not survive after losing their sidings and direct links to the Harlem.

Each of these three tales prove poignant snapshots of the drastically different White Plains of the early twentieth century. As evidenced by Dot’s unofficial timetable, a person living in New York City may have actually ventured to White Plains for the purpose of entertaining themselves at the hotel, restaurant and concert venue, and may have taken the train to do it. At one point in time the core area of White Plains surrounding the train station was both walkable and filled with businesses and entertainment.

The rise and fall of the Warren and Wetmore station in the city proved to be a poster child for the movement of urban renewal. Something that was once beautiful had degraded into a broken down and graffitied shadow of its former self. Tearing it all down and starting anew seemed like the best idea to planners and leadership at the time. In some ways, the razing of a neighborhood for the Bronx River Parkway’s construction was almost like a dry run, foreshadowing the future actions to take place in the area near the station. Many municipalities across Westchester and beyond experienced the taking and razing of homes and businesses for the progress of parkways and interstates, but far fewer of them went through the drastic step of erasing their entire downtown in the name of progress.

It may not have been paradise, but it got paved over, and today there’s a heck of a lot of parking lots. Was the complete erasure of downtown successful in attracting businesses? Certainly. But it erased a community and turned it into an imposing car-centric quasi-office park. As the dilapidated White Plains mall crumbles, and the Galleria reaches its functional end of life, new ideas are needed to reinvent downtown, and bring back the people that have long been kept away.

Special thanks to Patrick Raftery, Librarian at the Westchester County Historical Society. Posts like these would not be possible without the excellent archival photography found at the WCHS, and in the collections of the White Plains Public Library and the Westchester County Archives.

The connection between Dot & White Plains makes me curious about something. Mystery writer Lawrence Block has a recurring character named Dot (possibly short for Dorothy in this case) who lives in White Plains. Now I’m wondering if this is an easter egg, or just a coincidence?

Very interesting history. Sad that the old station was allowed to decay and be demolished, from the pictures, it looked like a very handsome building. Unfortunately, in its last years the New York Central RR was losing serious money and could not afford to maintain its old grand station buildings, and the Penn Central was in even worse shape.

It should be noted that years ago urban renewal was seen as a great idea. Many of the old buildings and neighborhoods targeted for demolition were indeed in lousy shape. Bright and shiny modern buildings were seen as a welcome improvement, as an attraction to revitalize a neighborhood. Old buildings that were left standing were modernized with dropped ceilings, fluorescent lighting, and air conditioning. Old decoration and ornamentation were covered up. It wasn’t just planners and politicians, but most of the public in those days applauded it as well. That was the style back then.

I am trying to find out about a hotel and tavern called the Harlem hotel at 21 main st white plains near the train station. The hotel was owned by my great grandfathers brother donato nannariello around 1905-1920s any information or pictures I would be very great full.

hi Steve,

i like to know that too..that was my great grandfather as well..

thanks for asking