As evening descends upon the Peruvian mountainside, I find myself aboard the lone evening Urubamba branch train, where I pepper our train’s conductor, Daniel, with questions. Sitting alongside the cab of this DMU, with its large front-facing picture window, I am granted a unique glimpse into the current limited operations of PeruRail’s Tramo Sur Oriente del Ferrocarril del Sur (Southeast Section of the Southern Railway).

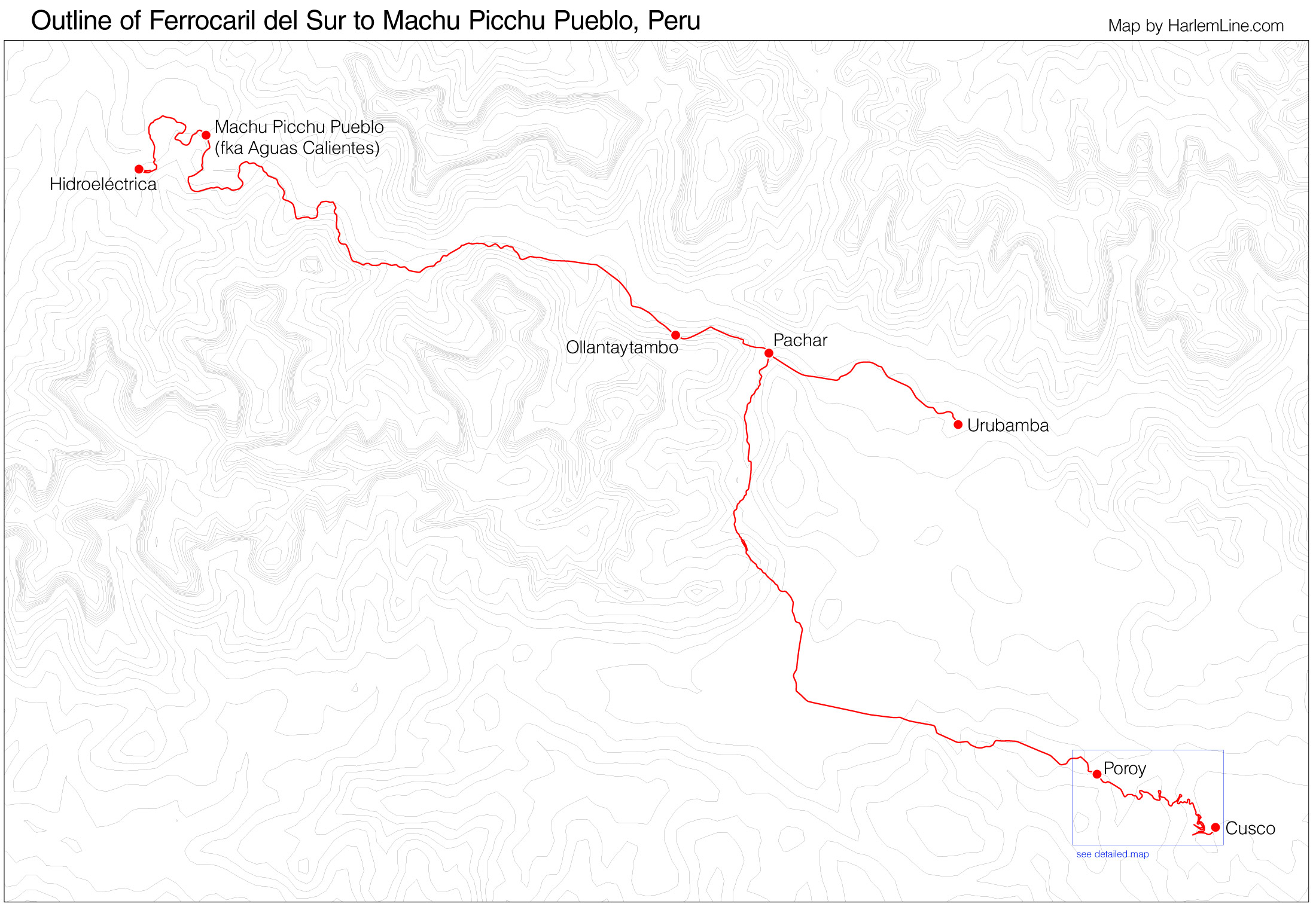

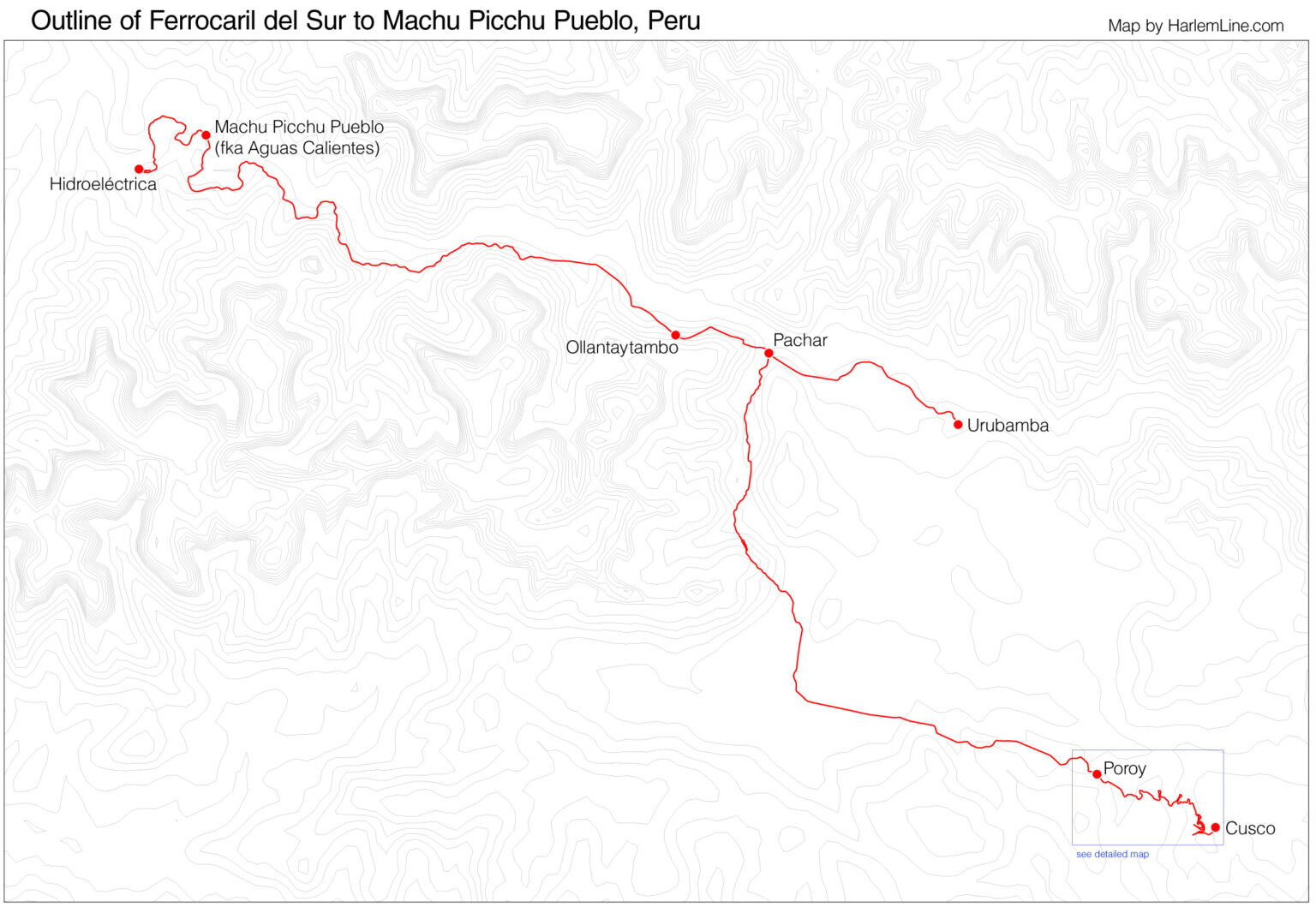

Connecting the main city of Cusco and the town of Urubamba to the inaccessible-by-car Machu Picchu Pueblo (formerly known as Aguas Calientes) the rail line serves as the primary gateway for access to Machu Picchu citadel. Ever since Hiram Bingham’s rediscovery of this 15th-century “Lost City of the Incas” in 1911, tourists have flocked to the site, and today it is Peru’s most visited tourist attraction. Construction of the rail line began around 1914, but was slow to develop—with the most mountainous portion between Cusco and Pachar taking nine years to build, with another six to reach Machu Picchu. Today, most of the trains are targeted to tourists, however a handful of heavily-subsidized local trains for Peruvian citizens operate daily, providing an important link between some very remote mountainside villages and the outside world.

Alas, during my visit “operational issues” have truncated all rail operations (with the exception of the five-times-per-week luxury Hiram Bingham train from Poroy) in favor of a bi-modal service: buses from Cusco to the road-accessible Ollantaytambo, then trains to the jungles beyond and Machu Picchu Pueblo. During normal times, service extends from the historic San Pedro station in Cusco (elevation 3410m) and slowly traverses an array of switchbacks and horseshoe curves to ascend nearly 280 meters before a slight descent into the Poroy station on the outskirts of the city (elevation 2487m). From there the line continues to descend into the Sacred Valley of the Incas.

The Urubamba branch, which extends from the Tambo del Inka hotel in Urubamba (elevation 2851m, and yes, of course I stayed at the hotel that had its very own train station!), joins up with the line at Pachar (elevation 2813m), a stone’s throw from the main midpoint station of Ollantaytambo (elevation 2804m). Then mirroring the path of the Urubamba River, the line traverses a series of tunnels before reaching Machu Picchu Pueblo (elevation 2080m). Most service terminates here, although a few trains daily carry passengers further to the end of the line at Hidroeléctrica (elevation 1794m, historically the line continued northward to Quillabamba, but was abandoned due to landslides).

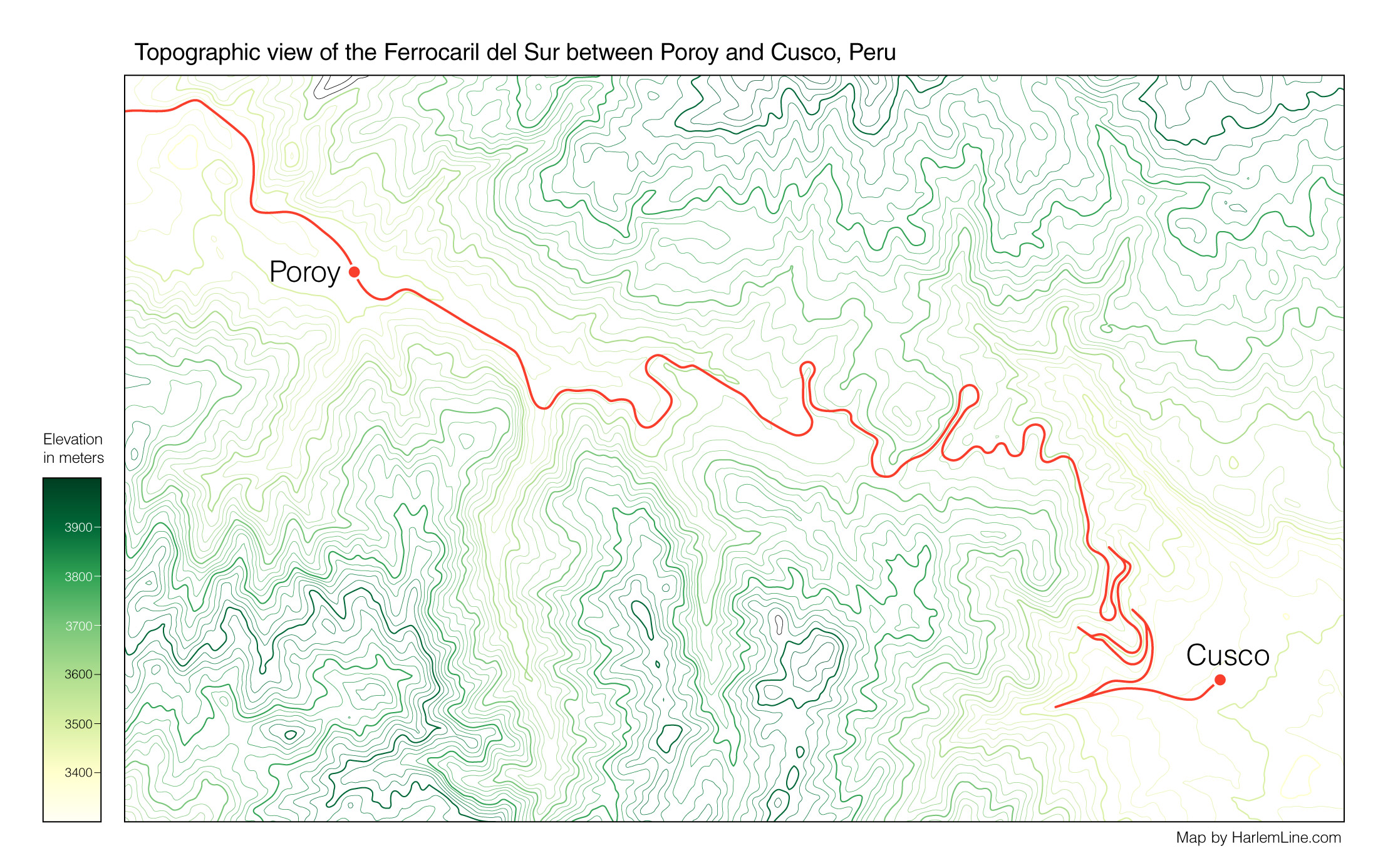

Contrary to what one would assume, Cusco—surrounded by an array of peaks, including the snow-capped Vilcabamba range—is situated at a higher elevation than Machu Picchu. Thus the railroad’s only notable elevation changes occur early on in the trip, with an average 4.9% grade to the first switchback and ultimately topping out around 3686 meters, as the train snakes its way out of Cusco and into Poroy. Both this ascent and skirting the middle ground between higher mountains has dictated the route, resulting in a rather frenetic-looking line on a map. Eventually, this wild line evens out, and the remainder of the route is relatively straightforward as it hugs the banks of the Urubamba River.

“Do people intentionally leave their animals near the tracks so they get hit?”

Through a combination of observations and chatting with Daniel using my limited Spanish, his limited English, and Google translate, a picture begins to emerge of this narrow-gauge train operation through the Andes.

Daniel chuckles when I ask about the animals. I tell him that this would surely be some sort of scam that someone would run at home, before getting lawyers involved in the hopes of a payout. But he assures me that the people are just looking to graze their animals, and due to Peruvian laws if an animal were to be hit, they wouldn’t be getting anything from the railroad. Nonetheless, the sight of so many animals tied down close to the tracks is jarring for me—notably the cow whose tether appeared to be fastened directly to one of the running rails.

Daniel describes in rough terms how the railroad operates, drawing a single track line and a few passing sidings across the back of one of his papers. I haven’t seen a single signal along the route, nor have I seen any lights, bells, gates, or other warning devices at any of the grade crossings we’ve passed. For that, they have a real live human guard to herd people away, at least in Machu Picchu Pueblo. But for the former, trains are instead given authorization via radio and recorded by form to access the territory.

To be a railroader is to expect the unexpected, but here one must really take the adage to heart. Whether it be the tough environment—there’s an “in case of minor landslides” shovel next to the cab—or the near-constant darting of people and pets across the tracks in front of our moving train—one must always be on their toes.

One crazy dog zigs and zags in front of us, eventually disappearing into my blind spot. Just when I was certain he was a goner, he reappears to the right of the tracks, running off to safety. Alas, I later spot a doghouse topped with a cross right next to the tracks near Pachar, and I can only imagine that it marks the spot where someone’s beloved friend was not so lucky.

Stationary objects also become hazards, as people leave all sorts of things close to the tracks. Even though the maximum speed of the line is only 45-kilometers-per-hour, dusk shrouds an errant motorcycle and we’re unable to fully stop in time before sideswiping it at low speed. Someone’s going to have some explaining to do…

Meanwhile, Daniel is constantly getting on and off the equipment to hand throw the switches along the route. As we near our final destination of Urubamba, he gets off yet again—this time to yell at a driver whose car is fouling the tracks. I watch the unfolding drama onboard, along with a gaggle of onlookers that have gathered around the tracks. Apparently the car cannot be moved because the keys have been locked inside. We all watch as the driver and his friends attempt to snag the inner door handle with a lasso of rope through the partially-open window. Even Daniel steps in to help, and before long the car is gone and we’re free to continue on our merry way. Our conductor has saved the day, and we all got a little taste of the unexpected along these rails.

Beautiful photography and very interesting reporting. A very different world. Thanks for sharing.