Every now and again I think back to my time in art school and some of the more interesting classes I attended while there. All students were required to take classes in disciplines like drawing, photography, painting, printmaking, design, and sculpture, but we were also able to choose more advanced classes in those areas as well. Sometimes I would pick things that just sounded cool, like metal casting (who wouldn’t want to start the forges, dress up in shiny silver colored heat protective suits and work with molten aluminum?). As fun as it was, I recall a review session where the professor lamented, “you’re probably really good at graphic design, but you’re not very good at this.” She was definitely right, though at that time I recall being rather disgruntled with the commentary.

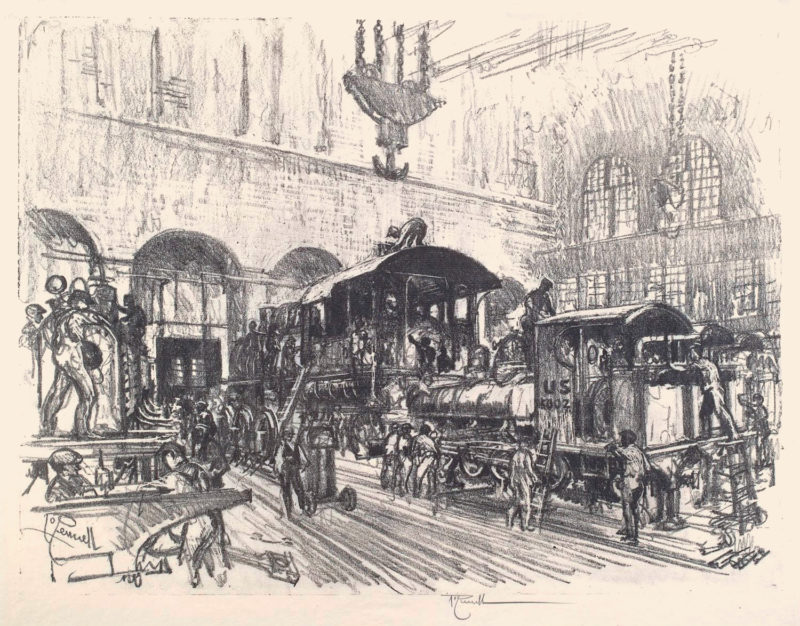

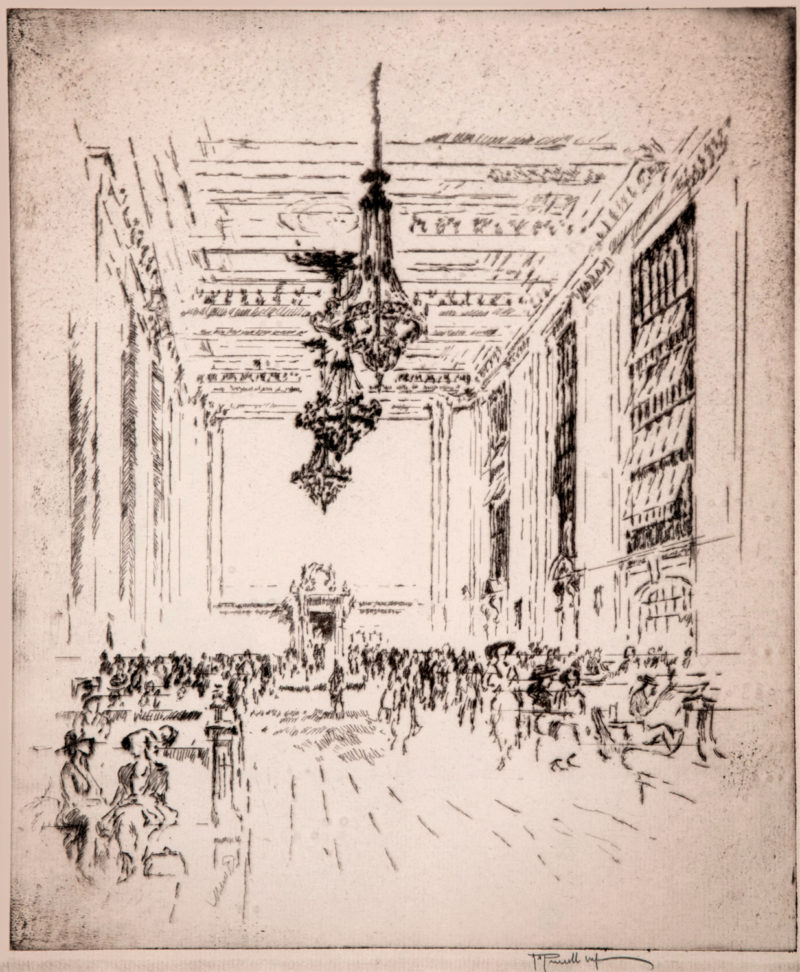

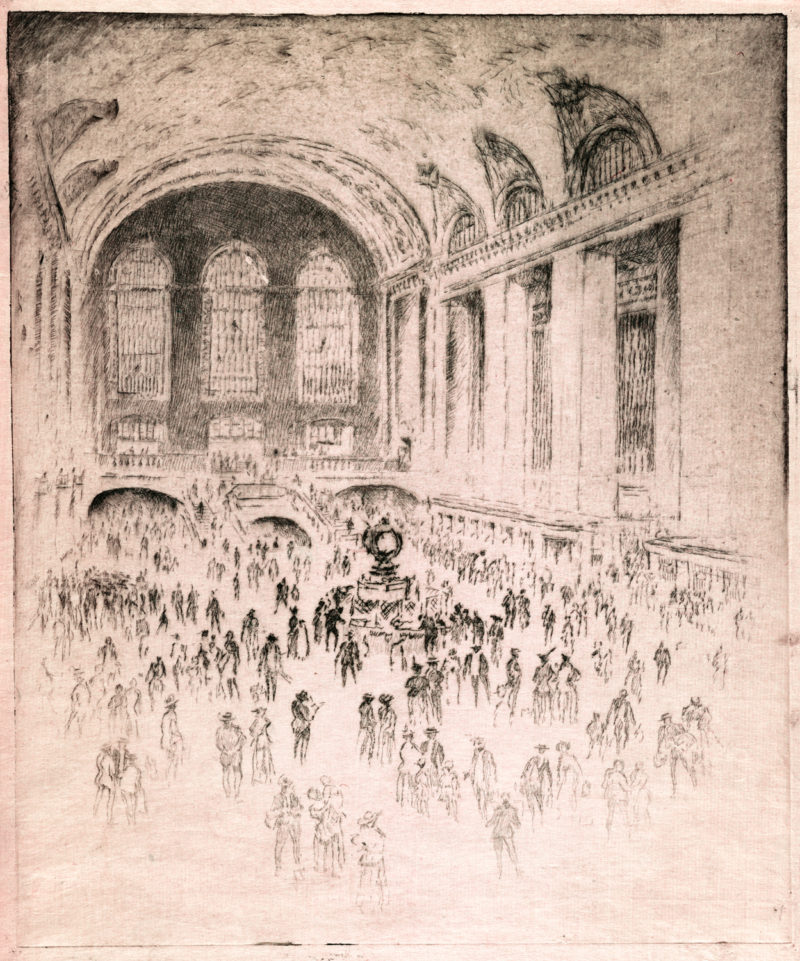

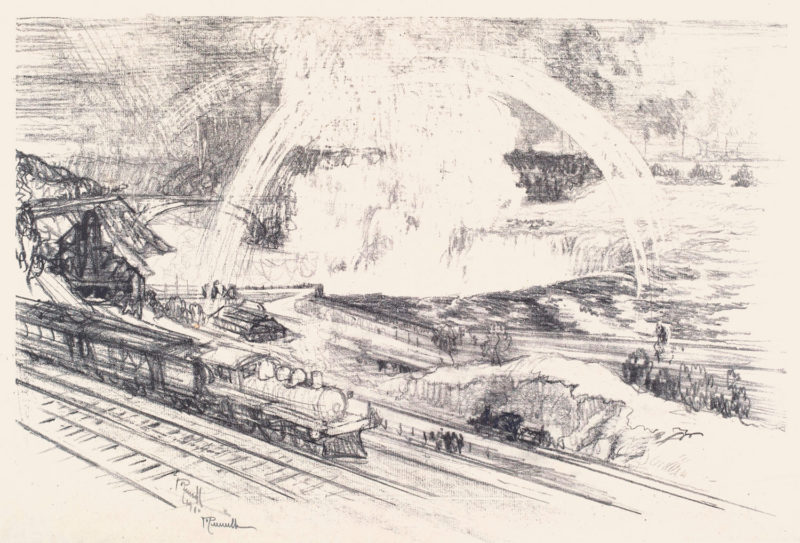

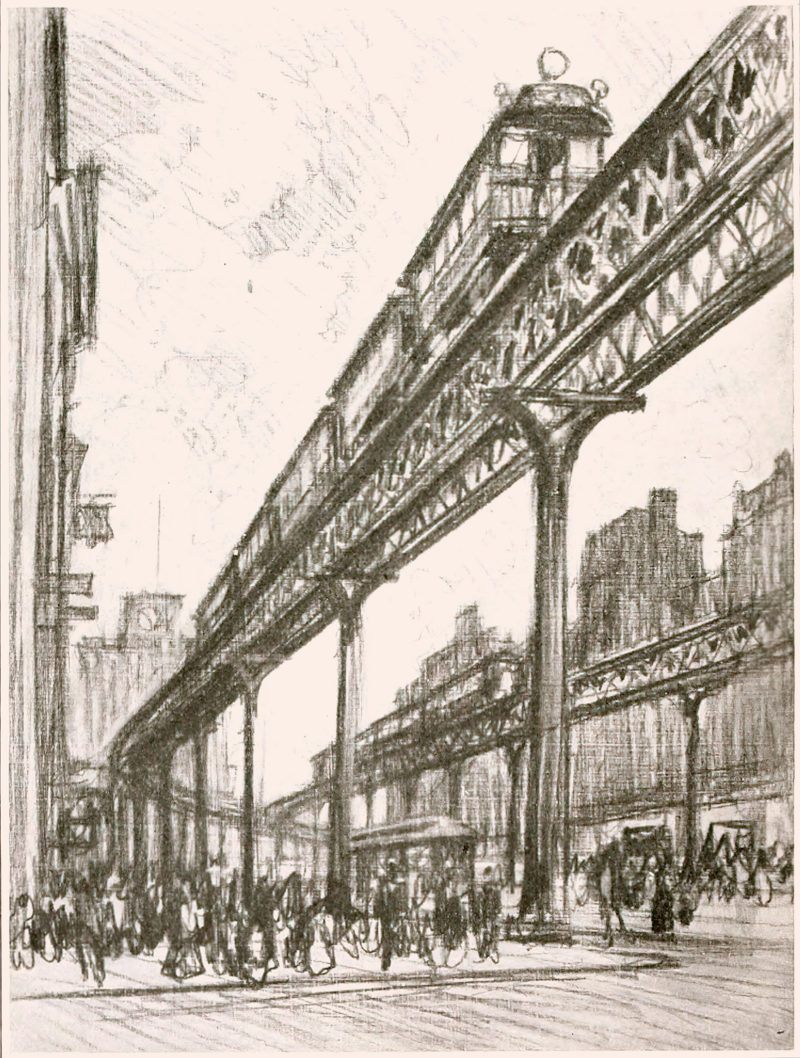

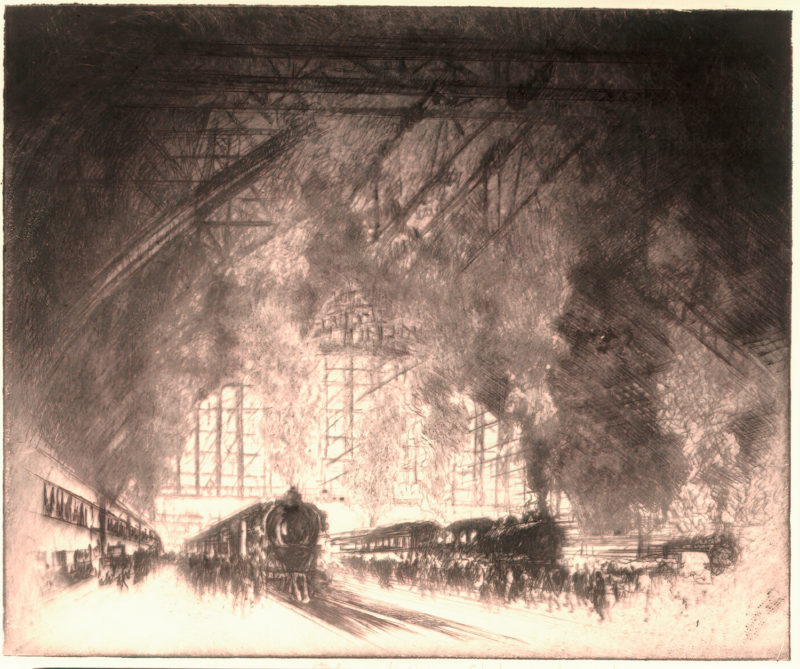

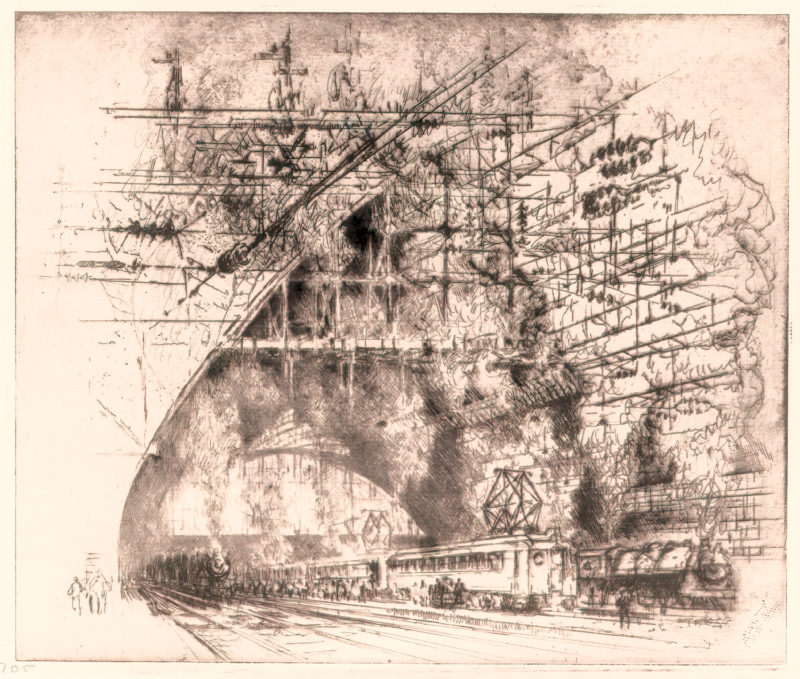

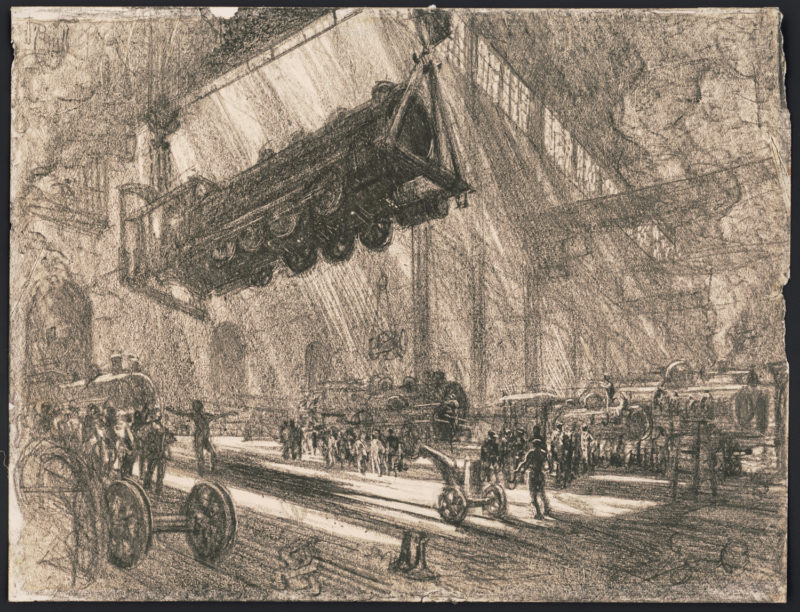

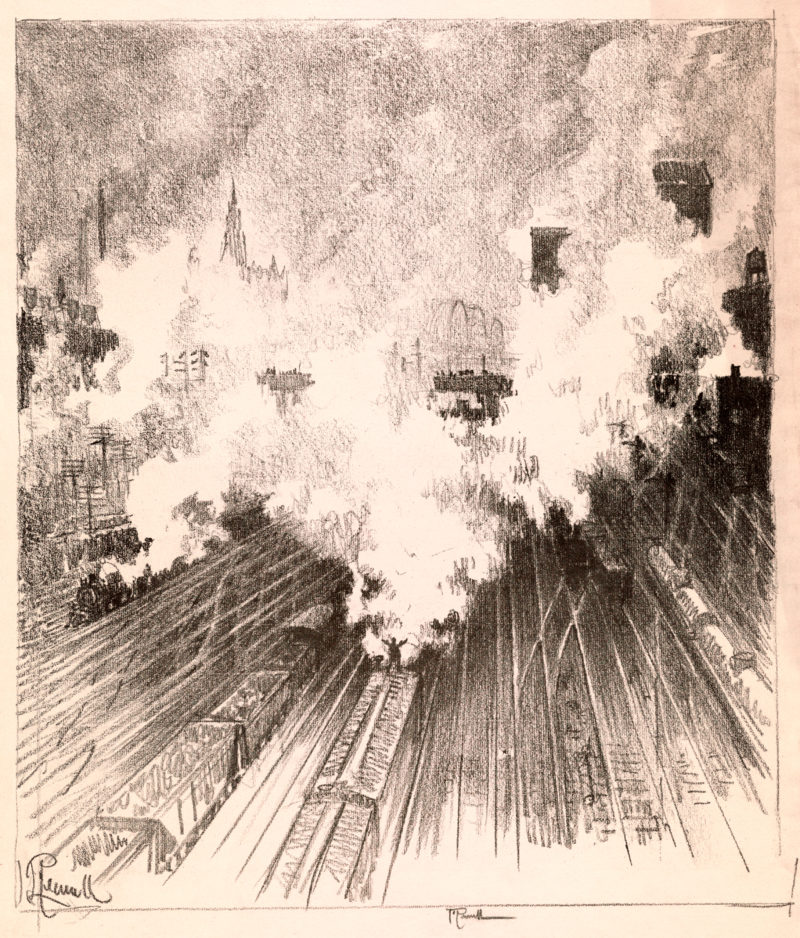

I was equally terrible at printmaking, yet found the process enjoyable, and could often be found in the print shop dropping acid—that is metal plates into acid baths to etch them for printing on an old timey press. Despite my lack of abilities, I think learning the process gave me a special appreciation for the craft. There is just something exceptionally lovely about the emotion that a print can convey, especially in the realm of railroading. From the light that filters through a massive train station window to the belches of smoke erupting from a locomotive, the subject matter provides a veritable playground for the skilled printmaker.

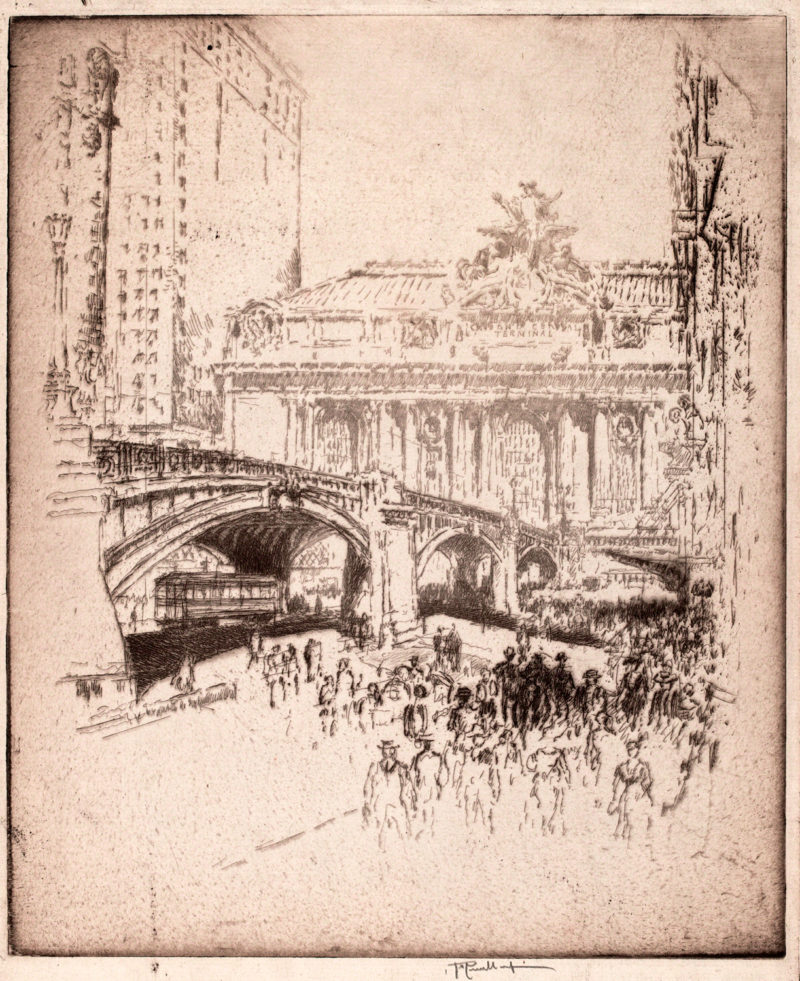

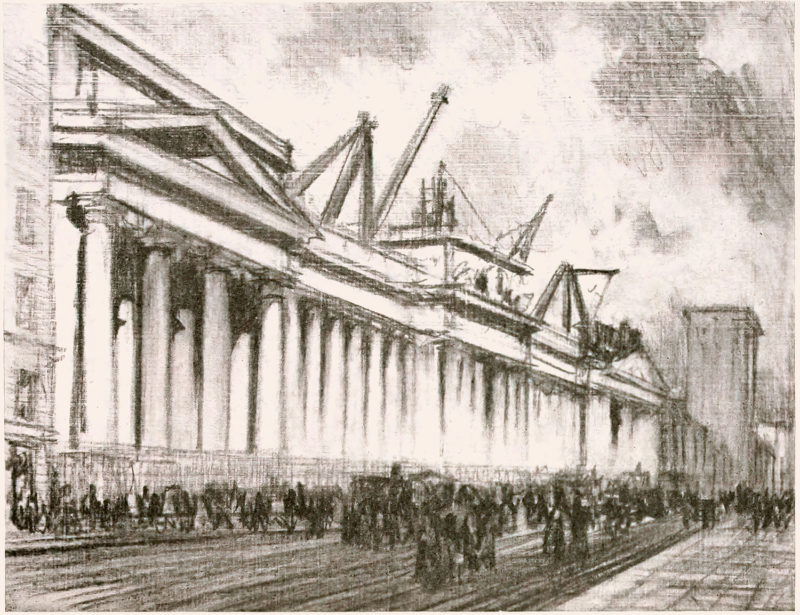

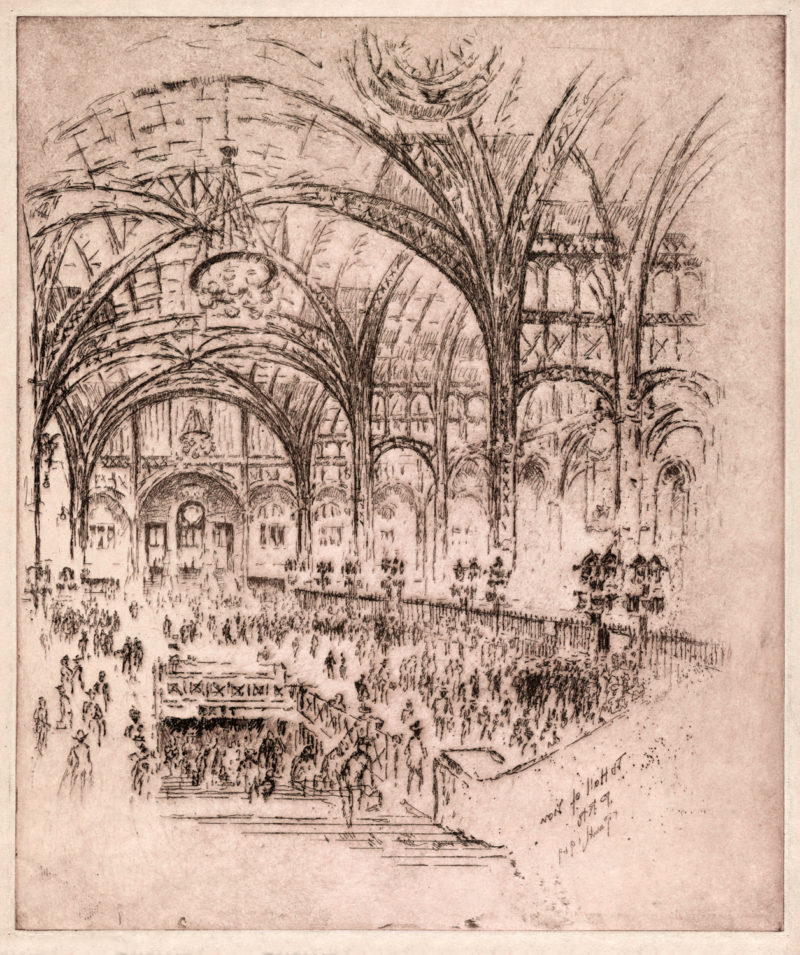

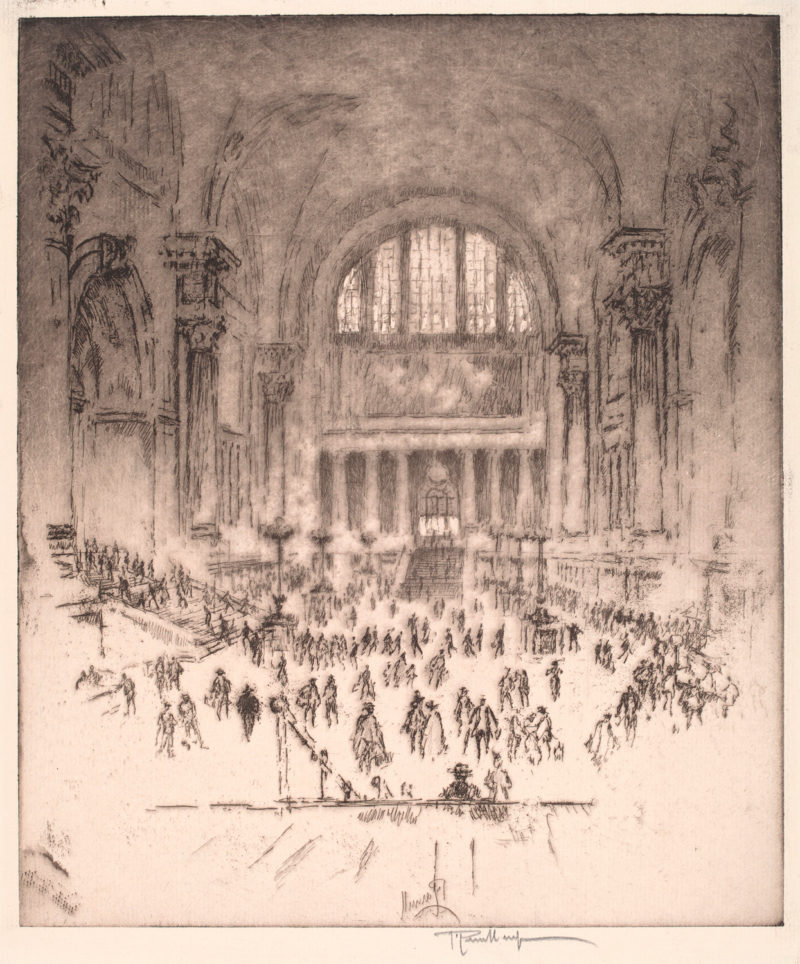

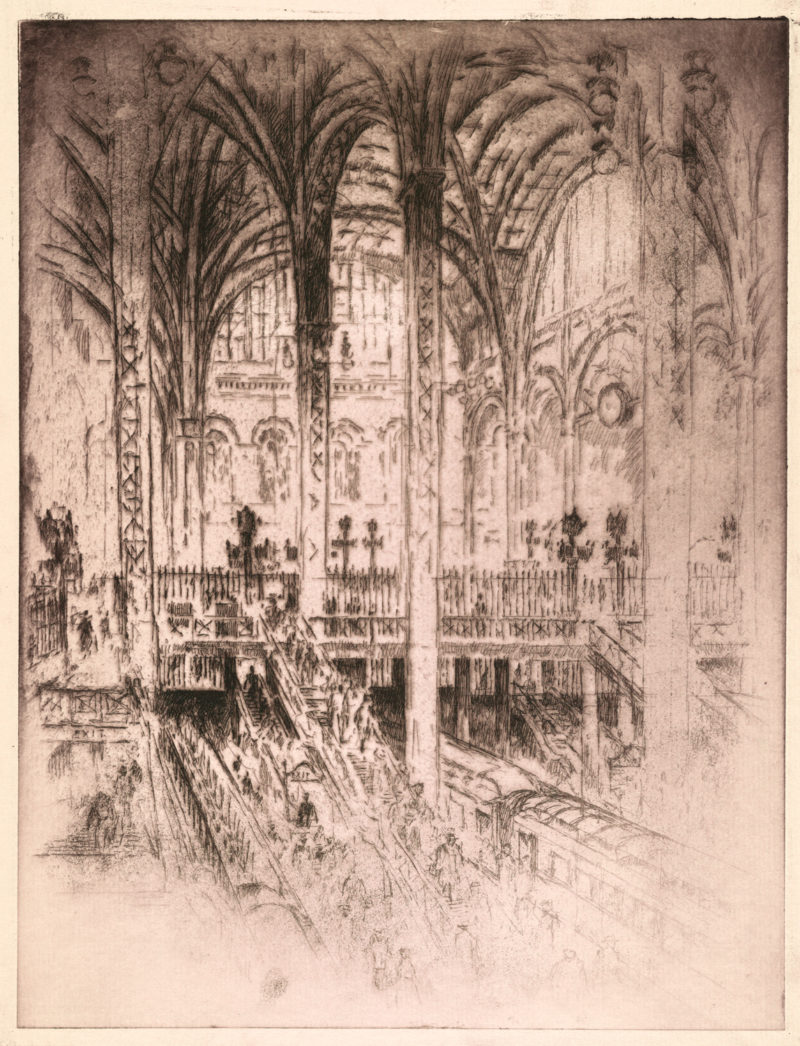

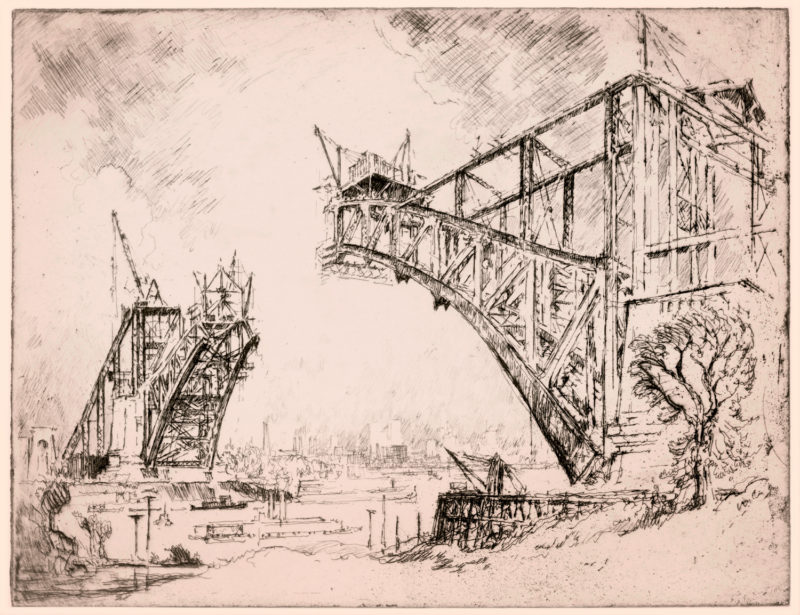

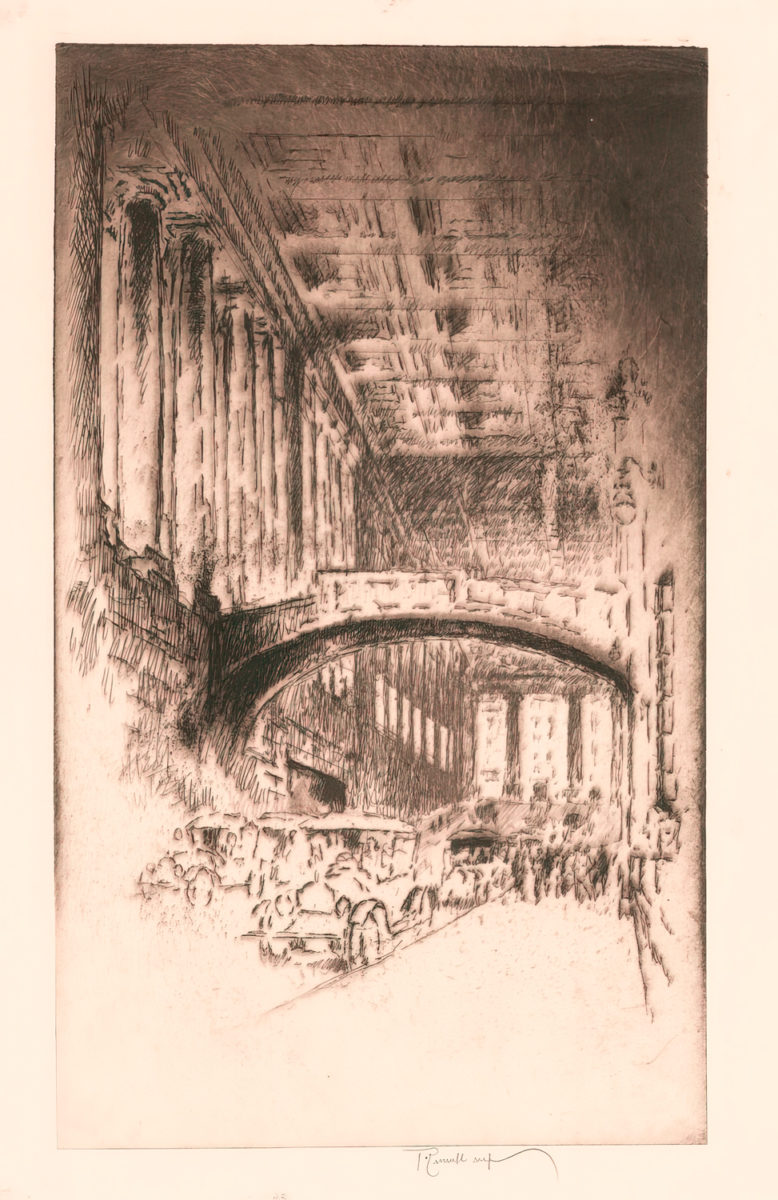

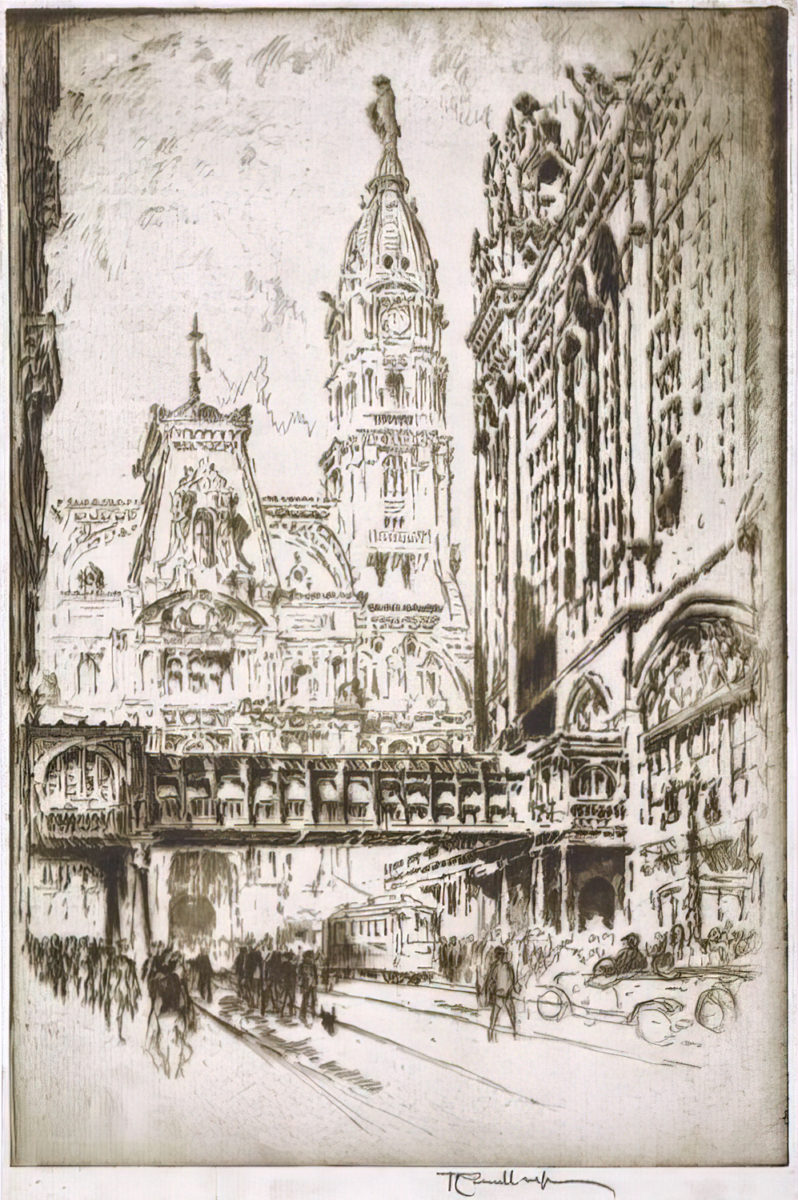

Enter Joseph Pennell. More than just skilled in the arts of printmaking, he was a master of the craft. Although his work illustrating articles for Harper’s and The Century Magazine took him around the world, his prints of railroading subjects in Pennsylvania (his home) and New York (the city that inspired him and eventually became his home) are especially memorable. Working mainly in the techniques of intaglio, aquatint, and lithography, his body of work captures notable moments in American railroading history—from the construction of New York’s Pennsylvania Station and Hell Gate Bridge, to lovely views of Grand Central Terminal, and Philadelphia’s long-gone Broad Street Station.

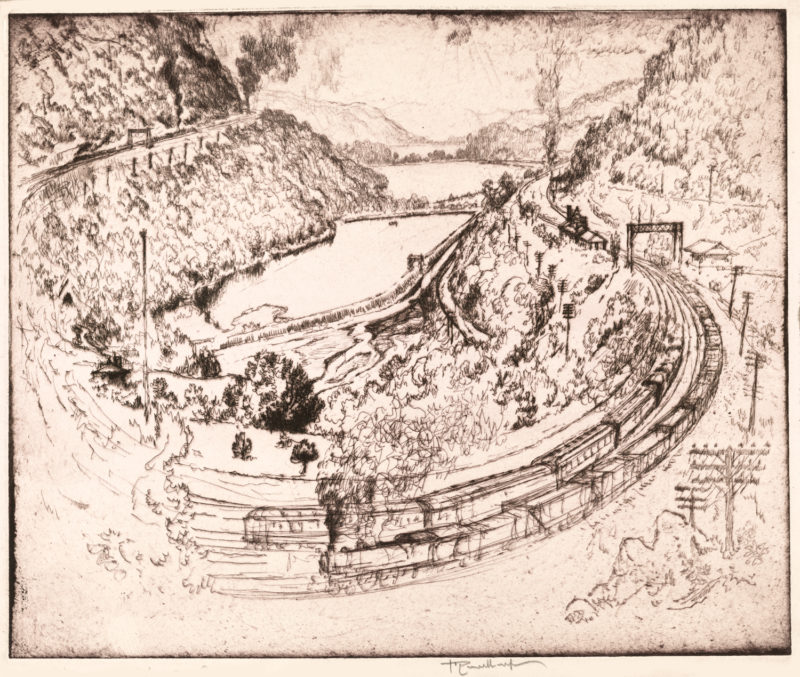

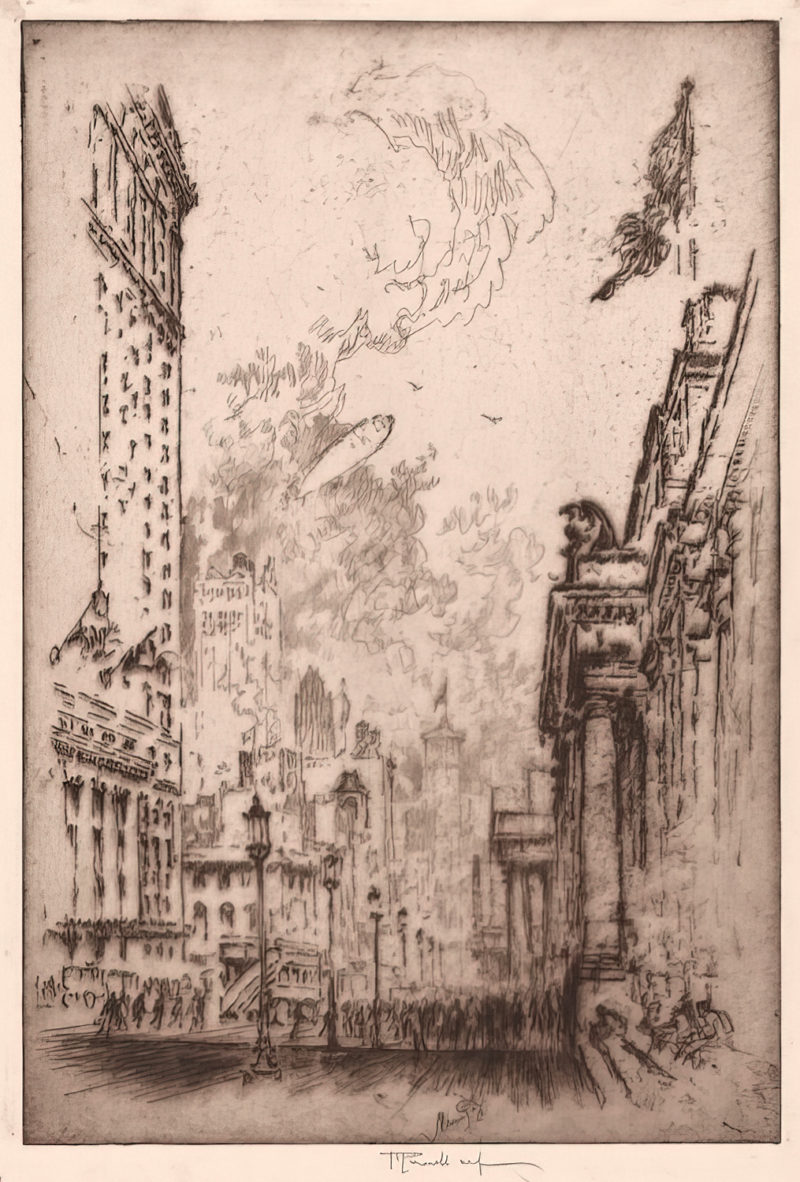

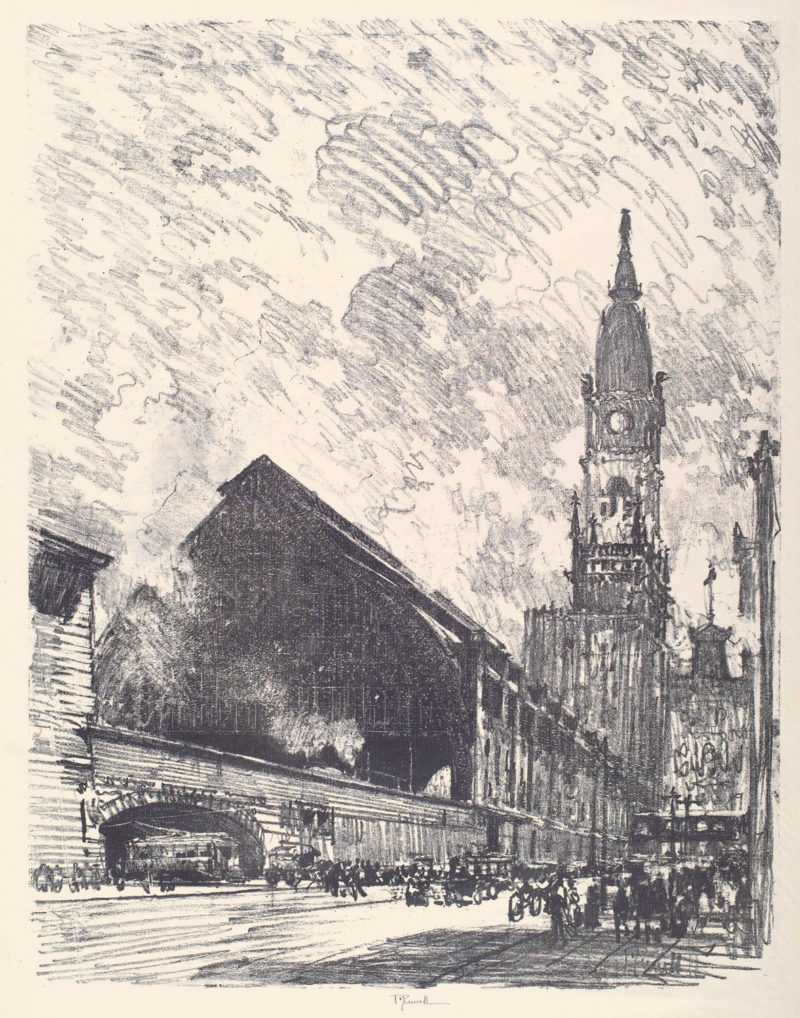

So what exactly goes into a print? For intaglio [above left], the process consists of coating a metal plate with a waxy substance, and then etching lines (backward, as the print is a reverse of the plate) with sharp tools into that wax. From there, the plate is placed in an acid bath, where the exposed lines are “bitten” into the plate. The wax is later removed, and the plate can be coated with ink and printed through a press to yield a version on paper. Aquatint works similarly, but allows for gradations in tone on the metal plate beyond the linework of intaglio. Lithography [above right] is a departure from the previous processes in that the artist uses a waxy crayon to draw an image onto a stone plate. Acid is likewise used, but here it creates a surface on the stone through a chemical reaction which will either hold or repel ink from which a print can be produced. While the acid process of intaglio requires drawings made of thin lines and points, lithographs are not constrained by this, and each technique can be used to evoke a completely different mood in the final print.

Pennell’s early printmaking work was predominantly in the technique of intaglio, but he later came to prefer the process of lithography. No matter which technique he used, Pennell had an incredible talent of conveying textures and emotions through his artful linework. He zealously attended to detail and was quite the perfectionist—trusting no one but himself to pull prints from his plates, and subsequently destroying his own plates after 50 printings to prevent the possibility of anyone finding them and attempting to print degraded images from them later.

Although Pennell’s work holds both artistic and historic merit, from today’s lens the man himself held many ethically problematic opinions. In fact, were he alive and working today, it is quite possible that he would have been rightfully “cancelled” for his racism. Yet in the time period in which he were alive, Pennell’s opinions were likely commonplace. As such, I think it is important to view his work in historical context. He was one of a long line of men who felt that art institutions should solely be the space of white males, and in his autobiography, The Adventures of an Illustrator, describes the admittance of Henry Ossawa Tanner to his “white [art] school” as “the coming of the n—–.” After detachedly recounting the time when Tanner was dragged out onto Broad Street and mock crucified to his easel (which Pennell may have been an active participant in), Pennell opines, “curiously, there never has been a great Negro or a great Jew artist in the history of the world.” Apart from the noteworthy moments he captures in his prints, Pennell’s work also encapsulates a sentiment of a world that we continue to strive to move beyond.

If you enjoyed this article, consider making a donation to the Friends of the Tanner House, the organization looking to restore Henry Ossawa Tanner’s house in Philadelphia.

Very interesting post. Excellent research.

I enjoyed learning about various printing technologies, seeing the railroad artwork, and learning about some unpleasant aspects of life in a different time. Thanks for sharing it.

P.S. While Broad Street Station in Philadelphia is long gone, nearby underground Suburban Station is still a busy commuter hub. City Hall (standing behind it) still stands as the municipal center of the city. The tower, with its statue of William Penn, remains a city landmark. The city’s two subway lines (Broad Street and Market-Frankford) meet underneath it. For many years, tradition had it that City Hall was to be the tallest building in the city, but eventually other buildings exceeded it.