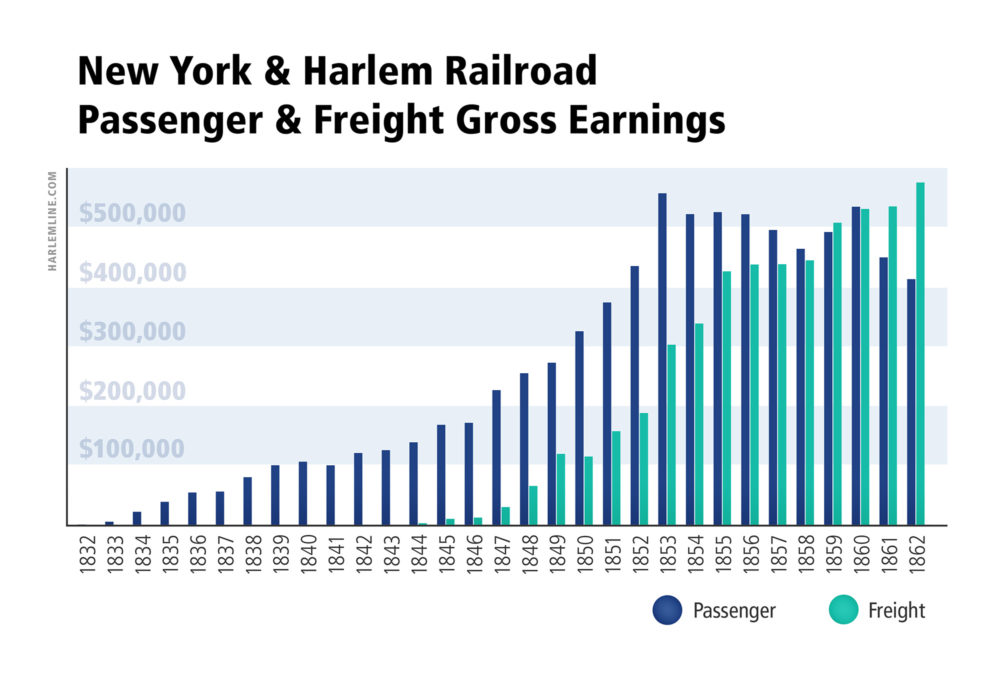

The earliest days of the New York and Harlem Railroad were ones fraught with hardship. As one of the earliest railroads in the United States, it was a guinea pig of sorts, a case study in the feasibility of roads of rails to be laid for the carrying passengers and goods. There was a technological learning curve to determine what worked, and what didn’t—from the type of rails (granite and wood were both early attempts), all the way to the techniques used to build it—including how to bore a tunnel before the invention of dynamite. This “figure it out as you go” approach led to exorbitant costs, almost dooming the road from the start. Newspapers of the day estimated the cost of the line through the northern part of Manhattan at $137,500 per mile (around $5.5 million in today’s dollars), due to the expensive tunnel at Yorkville, making it one of the most expensive “highways” ever built at that time in America (official figures put the cost at $104,375 per mile through Manhattan, but does not differentiate between the north and south end of the island). To put that cost into perspective, the average cost to build from the Harlem River to Williams Bridge was only $38,475 per mile, and from there to White Plains $11,277 per mile.

Beyond such high construction costs, the railroad’s stock was also prone to manipulation, and one of its presidents even went on to defraud investors with phony stock, absconding to France after being caught. It got bad enough that the Harlem’s stock certificates were seen as bearing little value beyond than the paper they were printed on. Add on the dangers of the road—safety too was one of those “figure it out as you go along” things—and you end up with a company with an absolutely abysmal reputation with the public. Thus when Cornelius Vanderbilt commenced his takeover, it was generally well perceived, with the Commodore’s shrewd business reputation restoring credibility to the beleaguered Harlem. Though Vanderbilt gets much of the credit for the early success of these rails, there was another man in the background who deserves some credit in how the Harlem truly came to be, and even how the rails are aligned to this day—Gouverneur Morris, Jr.

Gouverneur Morris, Jr.

Born in Morrisania in 1813 into the influential Morris family, Gouverneur’s uncle was a signer of the Declaration of Independence, and his father was one of the authors of the Constitution. The family owned much of what is today the Bronx, then the Manor of Morrisania in Westchester County. Only a toddler when his father passed, young Gouverneur was sole heir to nearly half of the original manor’s landholdings. It was under his ownership that the land would transition from sparsely populated farmland to a town of thousands. Morris envisioned a center of heavy industry, and with access to deep water, a vast network of shipping by sea and by land.

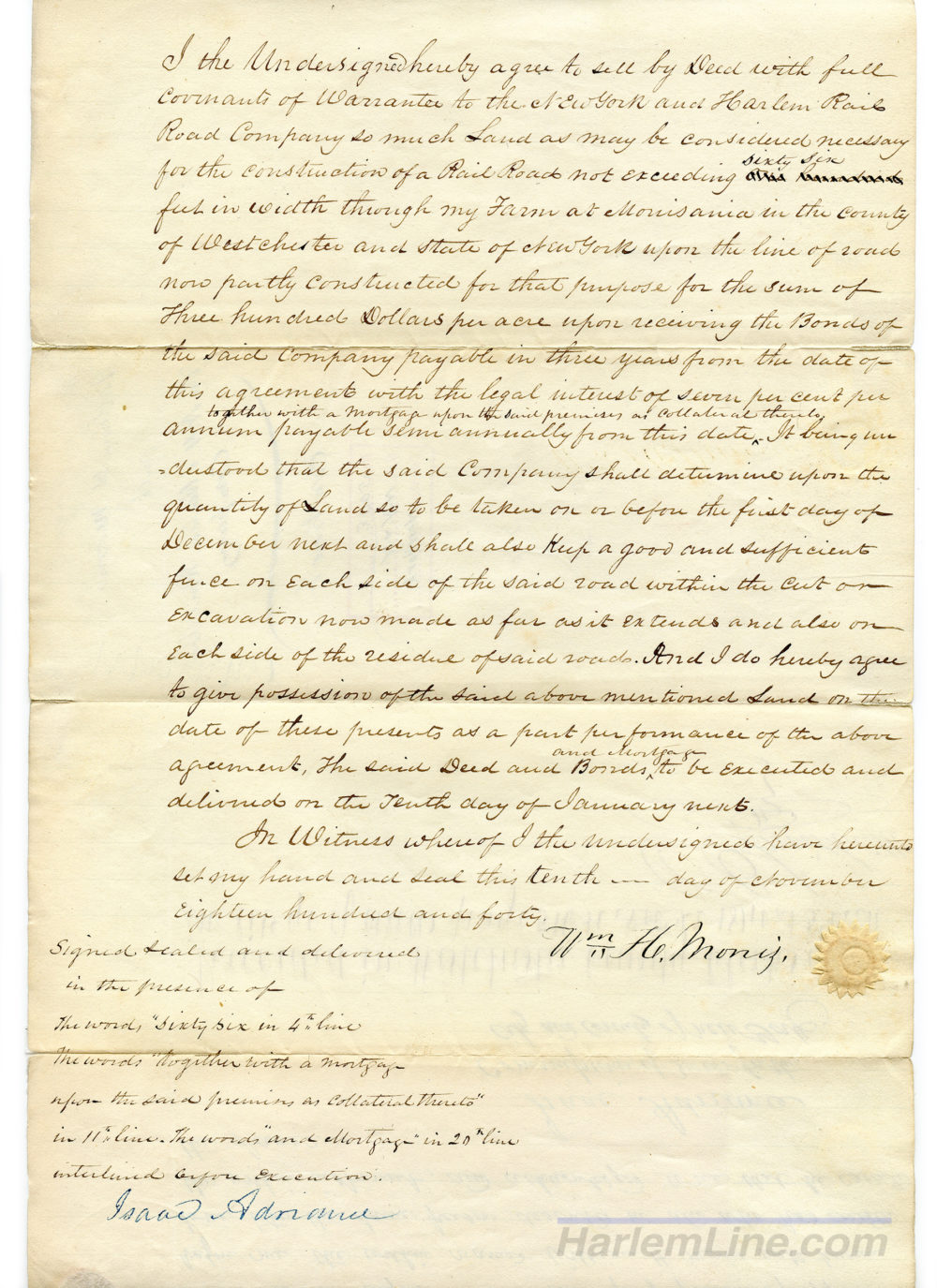

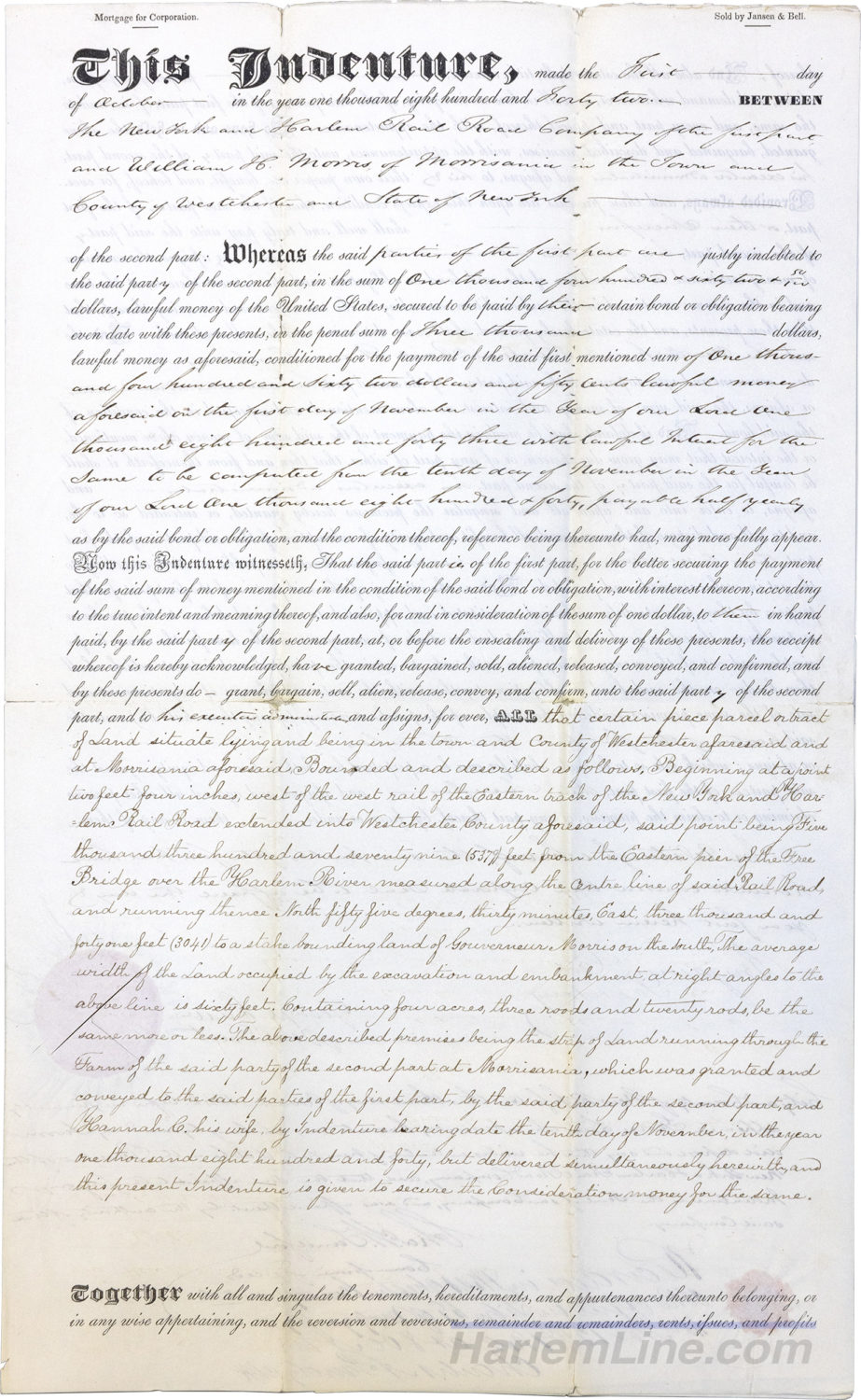

Morris was convinced that a railroad was integral to these dreams. He was an early backer of the New York and Albany Railroad, the road that the New York and Harlem was supposed to join up with at the banks of the Harlem River. But when the New York and Albany failed to materialize, Morris threw his support behind the New York and Harlem, which was eventually granted the charter to expand northward where the other had failed. Wielding significant power due to his family’s ownership of an existing bridge over the Harlem River, Morris facilitated the rights for the Harlem to use it to cross into what was then Westchester, and he, along with several of his family members, made deals with the Harlem for land to build ever northward.

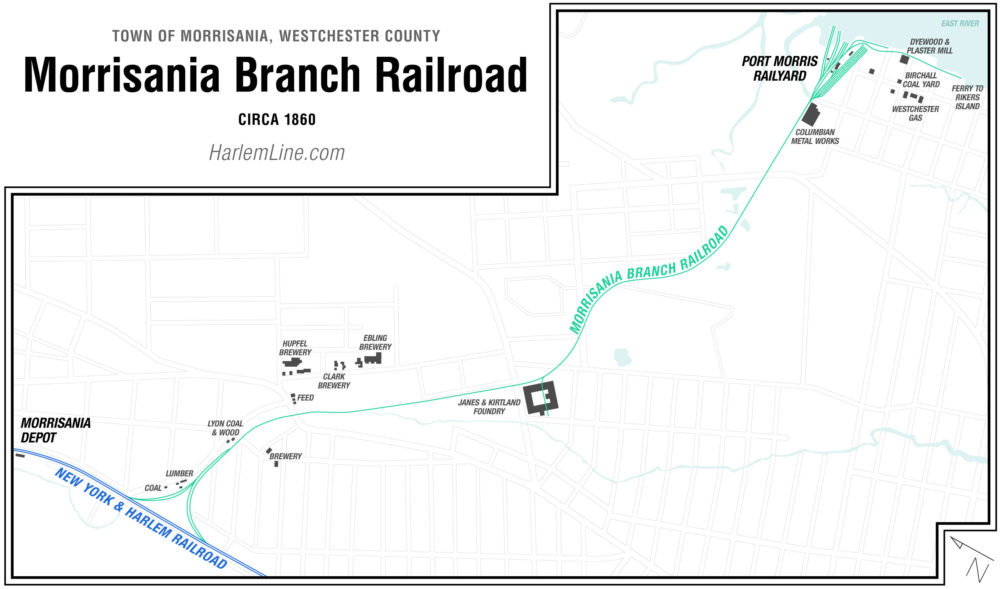

The Harlem reached Williamsbridge in 1842, and shortly thereafter Morris opened a private rail line across his estate, connecting to the newly arrived Harlem near what is now Melrose. He referred to this line as the Morrisania Branch Railroad, and the first commodity it carried was milk from the dairies on his farmland to the city. During the swill milk crisis, Morris and several other nearby dairymen including Thompson Decker (whose business would eventually become a part of Sheffield Farms through merger) were proponents of “pure milk” and lobbied the Harlem and other railroads for additional milk trains through upper Westchester and beyond. For decades milk remained an important commodity of the Harlem, with the famed Rutland Milk, or “Rut Milk” train, and shipments to Sheffield Farms’s expansive gravity milk plant near Melrose Junction.

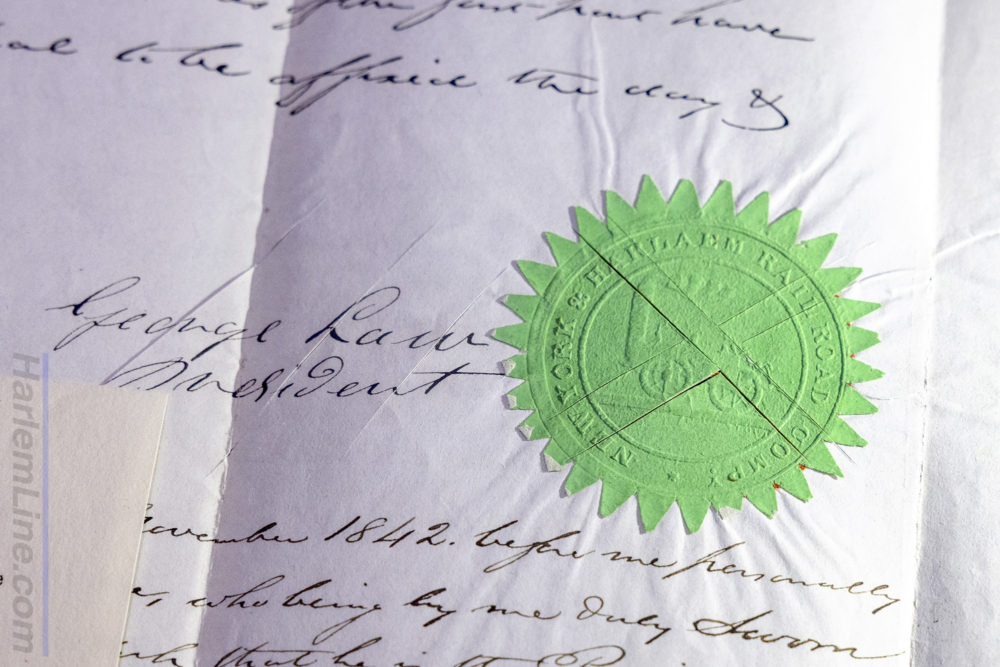

Land agreements between Morris family members and the New York and Harlem Railroad.

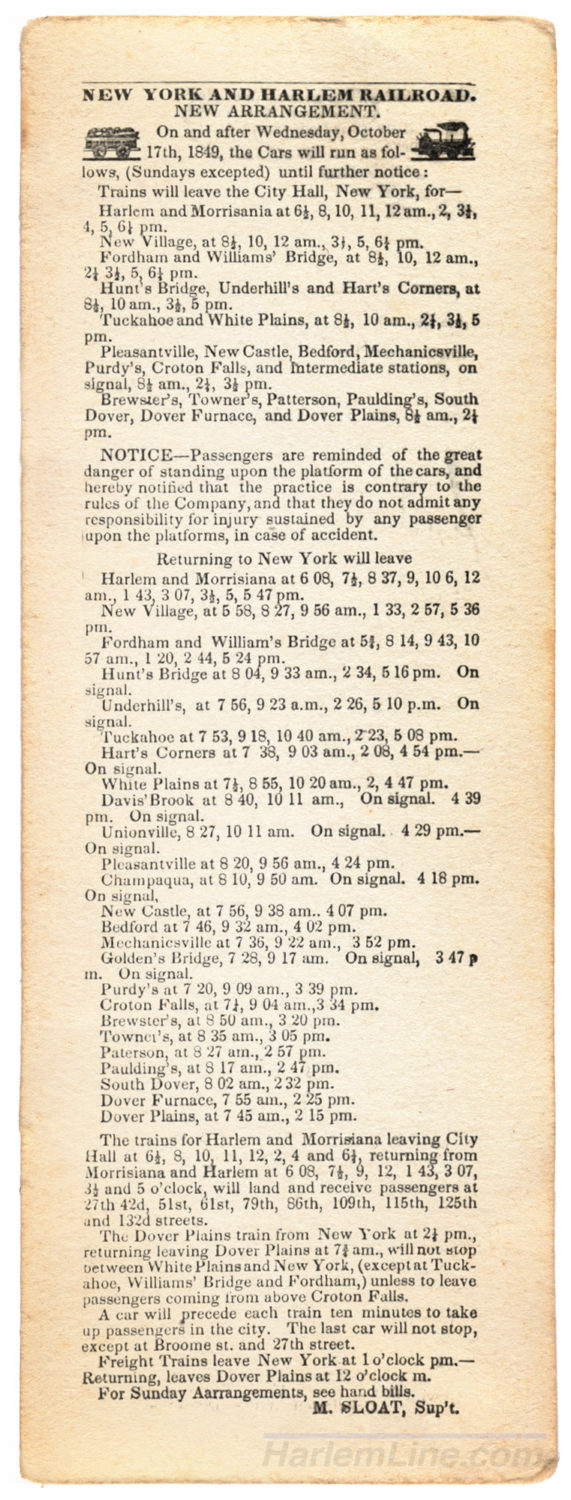

Founding Morrisania

By 1848 New York City was continuing to grow, and many men dreamed of escaping tenements and landlords, for a land they owned themselves. The Harlem’s expansion opened a new opportunity for such men—the ability to remain at their city jobs, but to likewise own their own homes in the “country.” A committee of families sharing such sentiment was formed at Military Hall in the Bowery, and led by Jordan Mott (who had previously purchased land from the Morrises to build his foundry in the area now named for him, Mott Haven), secured the purchase of 200 acres from Gouverneur Morris. After planning a grid of streets and reserving a piece of land for a rail depot, school, and public square, those 200 acres yielded 167 plots of land. At a subsequent committee meeting cards with each of the numbers 1 to 167 were placed in a box. The men each drew a card, and the number shown indicated their order in picking from the array of lots. These men in their New Village, eventually to be named Morrisania, were the Harlem Railroad’s first suburban commuters. Their new train stop saw fifteen trains a day, and the yearly price of commutation was $37.50 to ride any train, or at a discounted $30 a year to be restricted to ride one specifically designated commutation train in the morning and evening. Within several years a depot proper was constructed, and George Tremper was appointed the first Station Agent.

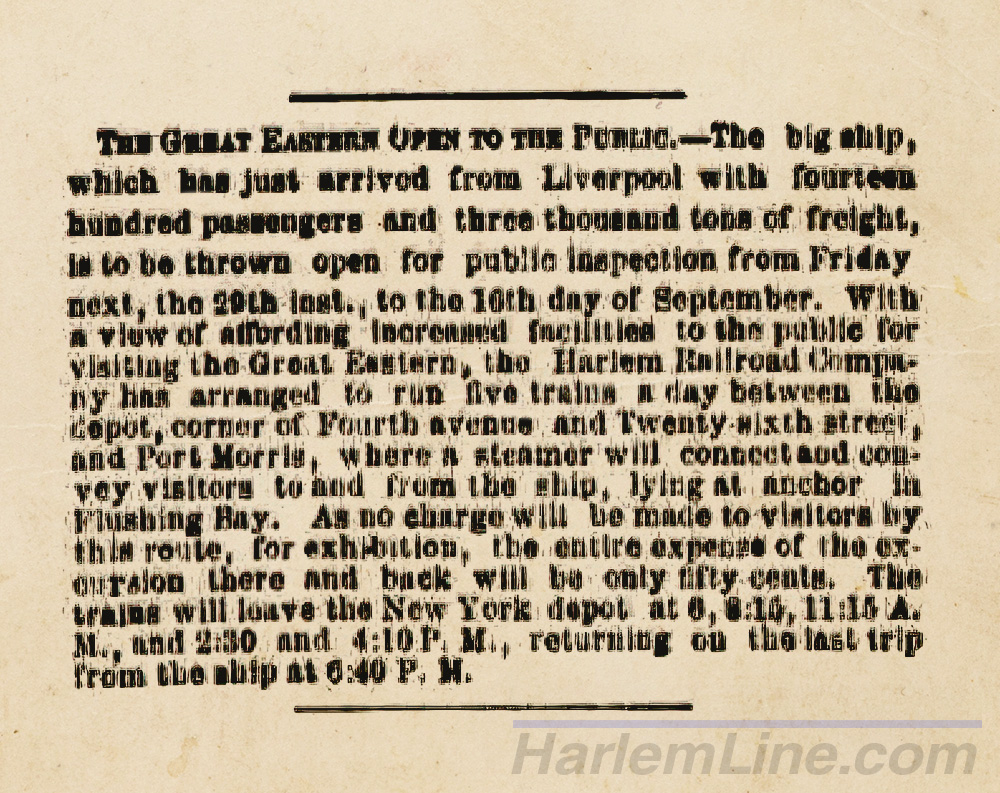

Gouverneur Morris would continue to sell off portions of his estate, and the town of Morrisania, and the villages like Melrose, Port Morris, and Claremont within would all continue to grow. Within the first year 68 homes would rise, and within two decades of Morris’s first sale to the committee in the Bowery there were 2,356 homes. Many heavy industries did pop up in the vicinity of Port Morris—beyond the coal and lumber yards German immigrants established a handful of breweries, and by the turn of the century pianos were rolling along the rails from an array of factories—but the dream of being New York City’s primary deep water port never materialized. Noteworthy ships such as the steamer Great Eastern did approach its waters, and the Morrisania Branch provided excursion passenger service for those curious to catch a glimpse of it.

In his History of Morrisania, resident and local historian Myron Finch’s colorful recollections of living adjacent to the Harlem mention a yard of six switches and a turntable at Melrose Junction, with four passenger trains a day over the branch to Port Morris with a connection to the ferry to Rikers Island, although this service was likely short lived. Meanwhile, the Harlem proper, although an integral part of their commuter village, was simultaneously seen as a “slaughter ground” by residents due to the derailments, collisions, and death it brought. Mishaps were unnervingly frequent, from trains colliding into the rear of another while they discharged passengers, to near misses of almost careening off the open drawbridge on the Harlem River. While aboard one train that derailed in the Yorkville Tunnel, Finch recalled:

![]() Cars [were] thrown across both tracks in a zig-zag direction, from under which we were compelled to crawl out as best we could, in pursuit of daylight! It was an exciting scene in the darkness of that tunnel and one well calculated to make us feel how providentially we had been preserved from a horrid death.

Cars [were] thrown across both tracks in a zig-zag direction, from under which we were compelled to crawl out as best we could, in pursuit of daylight! It was an exciting scene in the darkness of that tunnel and one well calculated to make us feel how providentially we had been preserved from a horrid death.

These accidents led to new rules regulating speed, signaling, and the offloading of passengers—an early example of the old adage that every railroad rule is written in blood.

Morrisania Branch to Port Morris Branch

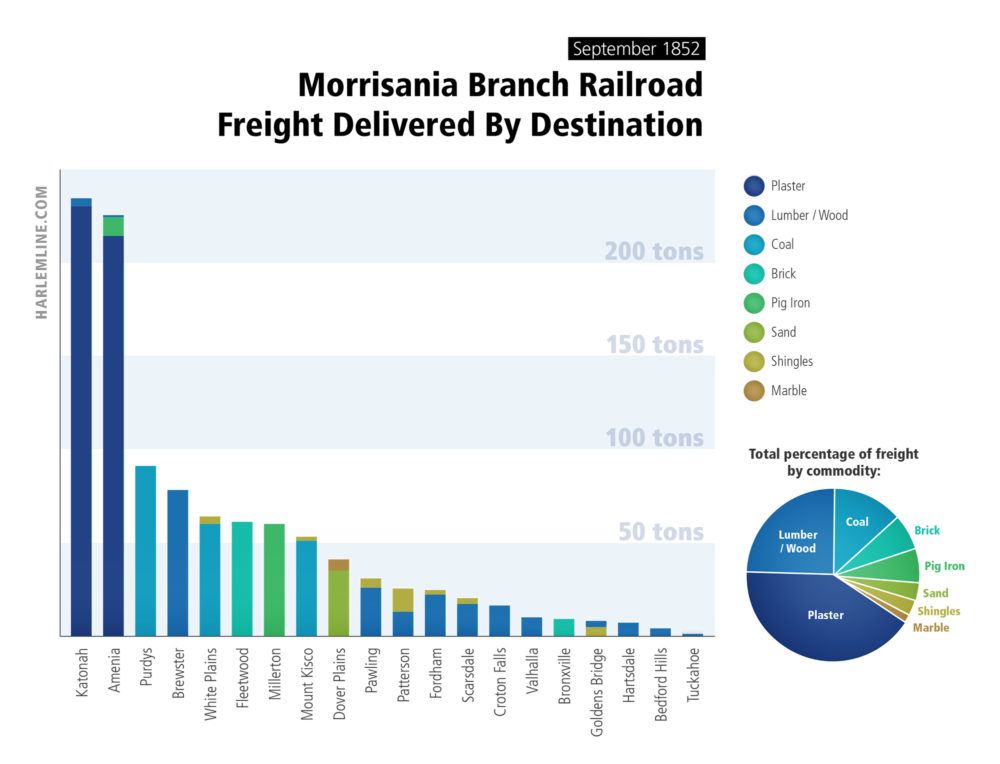

The Morrisania Branch Railroad quickly grew beyond shipments of milk and began carrying freight from the industries popping up around Port Morris. Marble, plaster, wood, and coal were all commodities moving across the branch, heading to locations along the New York and Harlem and beyond. A large grain elevator would eventually be constructed near Melrose, and the line would add two more yards to handle all of the traffic. Specially designed cars with oak frames and hinged trap doors on the bottom were ordered to carry coal. Even the foundry that produced the grand iron dome for the United States Capitol building could be found along the branch. According to lore, the iron for the dome was loaded onto railcars at the Janes & Kirtland Foundry’s industry track, taking a short jaunt down to the port to be loaded onto a ship for the longer journey to Washington DC.

Morris sold the his branch to the Harlem Railroad in 1853 for $118,000, where it subsequently became known as the Port Morris Branch. The original routing to Port Morris was at surface level along the perimeter of the Mary’s Park estate (the future St. Mary’s Park), but was upgraded during the railroad’s massive electrification project around 1905. At that time all remaining grade crossings were eliminated by sinking the track below the streets, and a tunnel was constructed to take the line underneath St. Mary’s Park. A massive power house was constructed by the waterside at Port Morris, twin to the one that still stands at Glenwood. This plant provided the power for the newly electrified Harlem Division. At its height, the branch had three yards—one at each end in Melrose and Port Morris, and another smaller yard at the approximate center along Westchester Avenue.

Ultimately, the branch’s unwieldy zig zag orientation as trains switched from the Harlem to the Hudson at Mott Haven, coupled with drainage issues and low height restrictions as a result of the 1905 track sinking would lead to its demise. The last trains would operate over the line in the late 90s, with the Oak Point Link superseding it upon opening in 1998. The derailment of a 125 car freight bound for Port Morris just a month before the Link opened highlighted the problematic nature of the branch—snarling traffic near Mott Haven blocked all three lines of Metro-North from accessing Manhattan. Simply antiquated, the branch unable to meet the needs of the modern era, and as-is was detrimental to the area’s burgeoning passenger traffic. The Port Morris Branch was officially abandoned in 2003, a final end to over 150 years of freight service.

These days, freight of any sort is a rarity on the Harlem. The final customer in the Bronx receives a shipment of a single carload around every three months, serviced by CSX.

Vanderbilt’s Ruse

Gouverneur Morris Jr. served as a Vice President of the New York and Harlem Railroad for several years, and was a partner in the firm Morris, Miller, and Schuyler, which built the Harlem’s “Albany Extension” from Dover Plains to Chatham (while Morris and Miller both had rail stops named for them, Schuyler was the aforementioned crooked president who sold phony stock, and thus missed out). Nearly two decades after selling his Morrisania Branch, Morris played an integral part in Cornelius Vanderbilt’s plans to link the Harlem with the Hudson River Railroad by chartering the Spuyten Duyvil and Port Morris Railroad (contrary to popular belief, the Port Morris Branch was never a part of the SD&PM). The move was designed to raise little suspicion, as Vanderbilt had not yet taken over the Hudson River Railroad, and if the Commodore himself had made moves to preemptively connect it to the Harlem, it would have gotten people talking! Thus Gouverneur Morris played an important role in bringing the Hudson into Grand Central through Mott Haven, an orientation that continues to this day.

Throughout his life, railroads remained one of Morris’s primary endeavors, and he served on the boards of several roads, as well as holding the presidency of the Vermont Valley Railroad. Although proud of the workingman’s village he helped create, Morris never saw himself as a city dweller, and was reportedly disappointed when Morrisania was annexed by New York City in 1874. He retired to Bartow-on-the-Sound, which was then a part of Pelham, now known as City Island (it too was annexed, albeit after Morris’s passing). Despite his accomplishments to railroading, Morris’s New York Times obituary consisted of 168 words about himself and his offspring, with a further 214 words devoted to his more famous father. Yet without Gouverneur Morris Jr., the New York and Harlem Railroad may never have crossed the banks of the Harlem River, nor reached Columbia County. Thus more than a century later, his indispensable contributions to the Harlem, and to the Bronx, are duly noted upon this page.

I hope you’re enjoying our recent series of posts covering the history of the Bronx. I had intended for this article to be published quite a while ago, but managed to get an appointment to view Gouverneur Morris Jr.’s papers at the New York Historical Society. His meticulous records provide some of the interesting tidbits found in today’s post, including the data on the types of freight carried and where they were delivered.

The Port Morris Branch has been a topic of interest for me for quite a while, likely because there seems to be so little written about it. I’ll be continuing with the theme of the history of the Bronx, and focusing on the Port Morris Branch, along with the real story of the Spuyten Duyvil and Port Morris Railroad, in the next few posts—so stay tuned!

interesting how things got started. it was a good article, lots of work and creatifity.

I really enjoyed this – thank you for your research and for writing this.

Had the air quality in NYC not degraded, I’d have ridden from Brewster today, for a day trip to the city for BusFest.