The last three decades of the 1800s were an interesting time for railroads running through the Bronx. With the Hudson River Railroad making moves to finally enter the east side of Manhattan, along with the rerouting of the Spuyten Duyvil and Port Morris to make it happen, things were beginning to align more closely with what we’re familiar with today. Also almost completely within this timeframe, a little rail line called the Jerome Park Railway was born and died. Although privately owned, much of the service was contracted out to the New York and Harlem Railroad, thus making it a de-facto branch of that line. Since I find many of these stories rather interesting, and likewise not extremely well known, I thought it would be fun to delve into these decades of history in the Bronx in the next few posts… starting off with the tale of that little line that everyone seemed to hate, yet would ride anyway…

Today’s Botanical Garden station has the honor of having the most name changes of any station along the Harlem. Although there are a few stations that have had two different names, Botanical Garden has had four within its 150 or so years of existence. Initially starting off with the name of Jerome Park, the station served the race course of the same name, which opened September 25, 1866. The course was a popular venue, hosting the first Belmont Stakes in 1867, and the first outdoor polo match in the United States in 1876. Upon opening the closest station for rail access was Fordham, but the Jerome Park station was established shortly thereafter, providing at least a walkable trip to the course.

Nonetheless, the walk from Jerome Park was still uphill and about a mile in length, so the establishment of alternate methods of access were considered for several years. An initial attempt to build a railway connecting the Harlem to the racetrack failed in 1876 due to litigation regarding the chosen route. A second attempt was made in 1880, this time successful, and the 1.67 mile road was constructed in a total of 34 days, opening on May 29th. President Leonard Jerome took fifty well-to-do invitees on a special opening excursion on the road that morning, departing Grand Central at 11 AM, and arriving in time for a fancy lunch at the course’s clubhouse.

The new partially elevated tracks ran to a small depot that had not yet been completed behind the track’s grandstand, with a wooden bridge connecting the two structures. For the opening of the line, a simple platform greeted the esteemed guests. After a lunch filled with toasts to good health and the celebration of the new line, the guests returned to their train for a 2 PM departure. All-in-all, it seemed to be a rather chaste celebration in comparison to the boozy excursion that marked the opening of the line to White Plains.

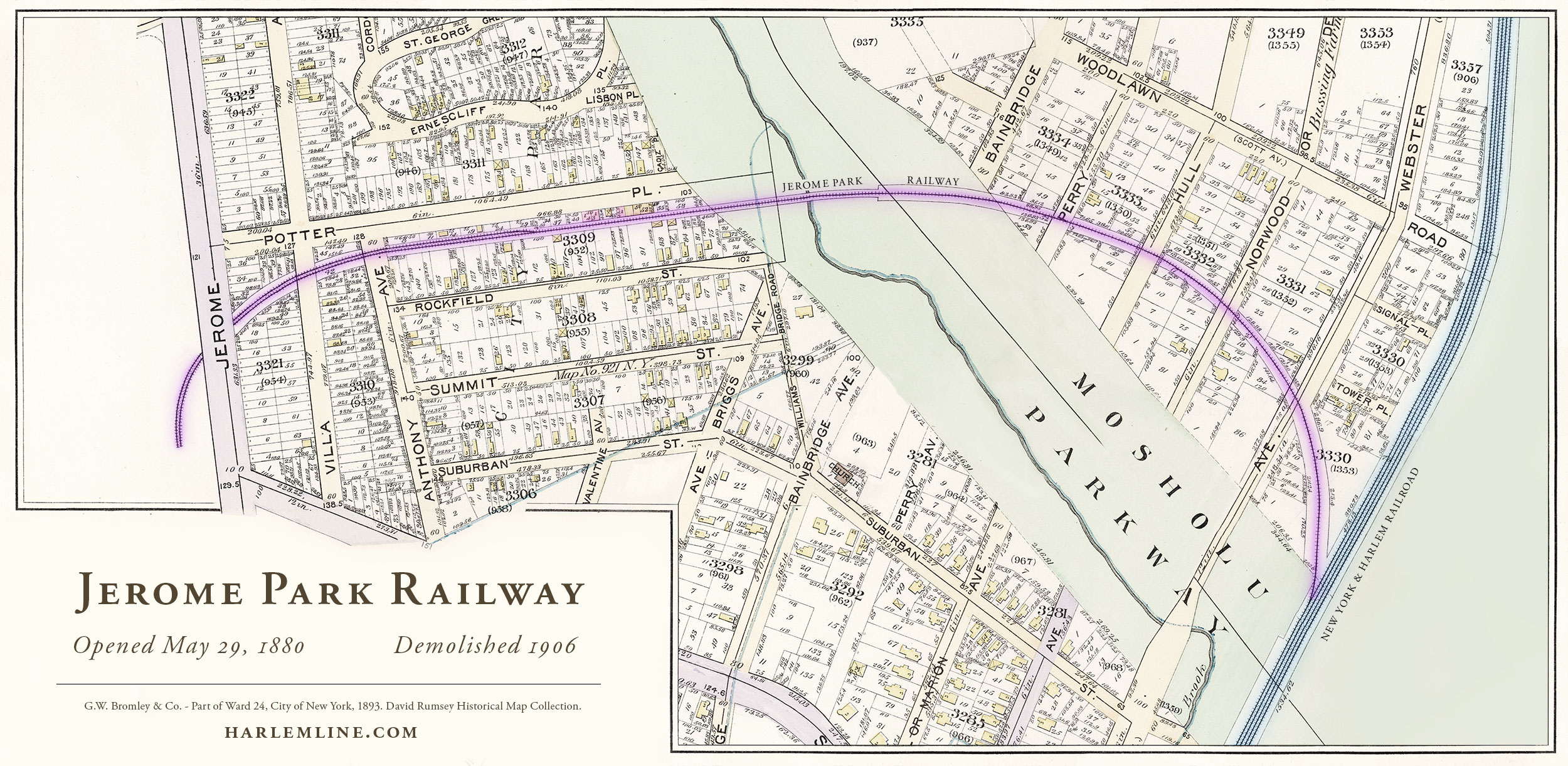

Map of the route of the Jerome Park Railway, highlighted in purple, extending from the Harlem just beyond the current Botanical Garden station.

Race day through trains were operated from Grand Central Depot with a fare of 60 cents round trip (20 cents more than a round trip to Jerome Park on the Harlem proper). Decoration Day (referred to as Memorial Day today) was an extremely popular day for the races, and over ten thousand people crammed Grand Central Depot to board trains, with two-thirds of them going either to Jerome Park, or to pay their respects at the Woodlawn Cemetery. The crowd at the depot was so large that extra police were summoned, at one point barring further patrons from entering. The two main ticket offices had lines that were so long, a third impromptu office was set up to sell tickets, but even that was not enough to accommodate the throng. Over 4,500 tickets were sold for the 1:45, 2:10, and 2:30 through trains to the raceway, and many other tickets were sold to Fordham for those who could not get onboard one of the specials.

This first day of opening to the public essentially set the tone for the just over one decade of existence of this branch. It was extremely popular, yet generally reviled due to the massive crowds and the inability of the infrastructure to accommodate them. 4,500 tickets were sold on those first specials, yet across the three trains there were only 2,160 seats. A less-than-happy rider recalled that on one trip “[people were] packed into the cars until they were so uncomfortably crowded that ladies and even strong, robust men almost had the life crushed out of them.” People would get extremely irate, write angry letters to both the editor and to the Commodore, yet would forget about these troubles in the off-season and be back to ride the trains again in the spring. All this despite lines extending from ticket booths all the way out the depot, onto the sidewalk, and around the corner, massive throngs of people, and late trains that sometimes even missed part of the races. As one letter writer concluded, “Commodore Vanderbilt does not care in the least what anybody says about his management while he is comfortable in the certainty that they can do nothing.”

Although some of the blame realistically could be placed on the Harlem for their operation of the trains, especially in regard to on time performance, there was much outside their control. Initial plans for the Jerome Park Railway called for a double tracked line, though it was never constructed this way. A second track only existed at the end of the line near the depot for the racetrack. Without additional tracks to run on, it was largely impossible for the Harlem to increase the amount of service and end the overcrowding problem that plagued the line from its inception. Complaints were plentiful enough that an announcement was made in 1887 that work would soon begin to double track the line and create more sidings near the track to allow for additional service, but these plans never came to fruition. As time ticked on, it became increasingly obvious that the Jerome Park Racetrack would not be around much longer.

The beginning of the end for the Jerome Park Railway was the closure of the raceway as the new site for a new reservoir for the city. The site had been identified as the best place for the reservoir around 1886, yet was subject to negotiations for the acquisition of the property. The race track finally closed after the 1894 season, and became property of the city on January 1, 1895. The railway branch was eventually leased to John B. McDonald, a contractor that had worked on the building of the IRT subway, and was hired to work on the excavation of the area around the reservoir. McDonald used the line, along with an extra four miles of temporary trackage that he constructed extending over the Harlem’s tracks out the area near Parkchester, to fill in the marshlands for development.

Images from the excavation for the Jerome Park Reservoir, utilizing the tracks of the Jerome Park Railway.

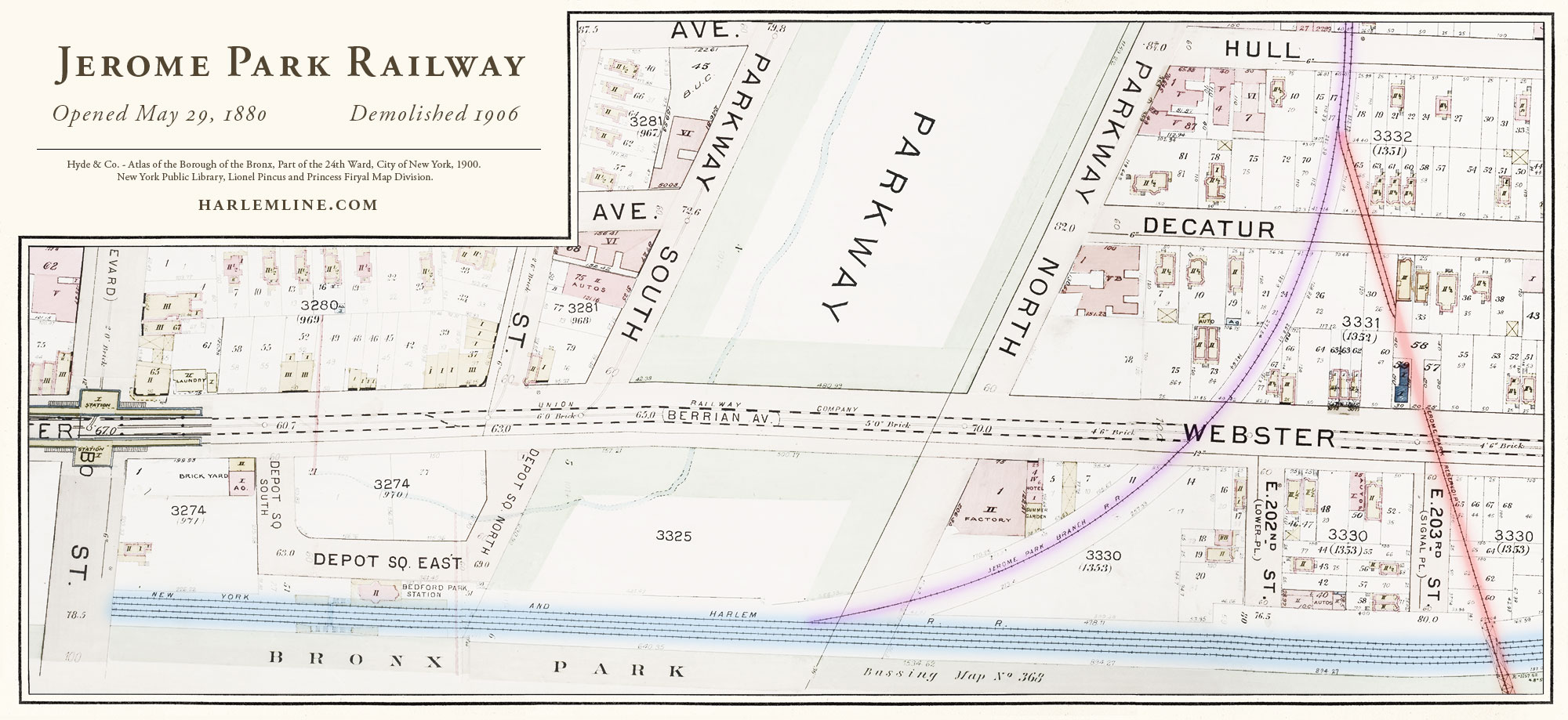

Highlighted in red, part of the temporary line that John B. McDonald constructed for the dumping of excavated material. This line extended four miles through Bronx Park and following along the Pelham Parkway to the marshlands.

Lying disused for several years, Bronx Borough President Louis Haffen ordered the remainder of the branch’s tracks to be torn up across Webster Avenue on May 6th, 1906, and expected the section between Willow Avenue and Bronx Park to be removed the day afterward. Haffen had accused some “mystery opposition” of stopping previous plans to remove the tracks, and fully expected the Harlem to object to the removal… yet no further objection ever came. Just 26 years after its construction, the Jerome Park Railway was officially dead.

As for the station along the Harlem proper, around 1887 Jerome Park was renamed Bedford Park after the neighborhood it was located, likely due to confusion with the branch itself. Just a few years later it was again renamed to Bronx Park, reflecting the recently opened park alongside it, where the Botanical Garden was established. Timetables often included a notation that Bronx Park was the location of the Botanical Garden, and eventually it just became easier to outright rename the station yet again to its current iteration—Botanical Garden.

Thank you for writing about this. I didn’t even know this one existed. I had thought the Morris Park Racetrack had been the only racetrack to be served by its own spur.

Interestingly, if you use Google Earth (or Maps with the Satellite layer), there is a building/space close to the corner of Jerome Avenue and East 204th Street that still shows the curve.

Speaking of horse racing, NJ Transit announced a promotion for its 2023 train service to Monmouth Park.

https://www.njtransit.com/monmouth-park

NJ Transit announced special rail service between Hoboken and Far Hills to transport customers to and from the 103rd running of the Far Hills Race Meeting on Saturday, October 19, 2024. see:

https://www.njtransit.com/press-releases/nj-transit-announces-special-rail-service-far-hills-race-meeting-3