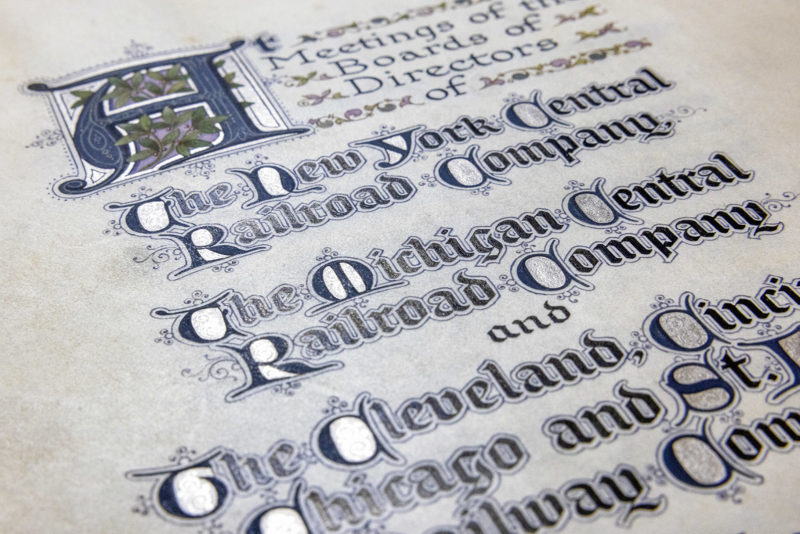

When someone brings up the topic of illuminated manuscripts, I tend to mentally picture an old monk sequestered in a monastery creating elaborate illustrations and fancy letters in a hand printed version of the bible. Yet in reality, the term “illuminated” simply refers to the incorporation of gold or silver leaf, or pigments, into the images and lettering. Plenty of different types of documents can be considered “illuminated”—and in the more modern era these are often ceremonial or formal documents, like diplomas.

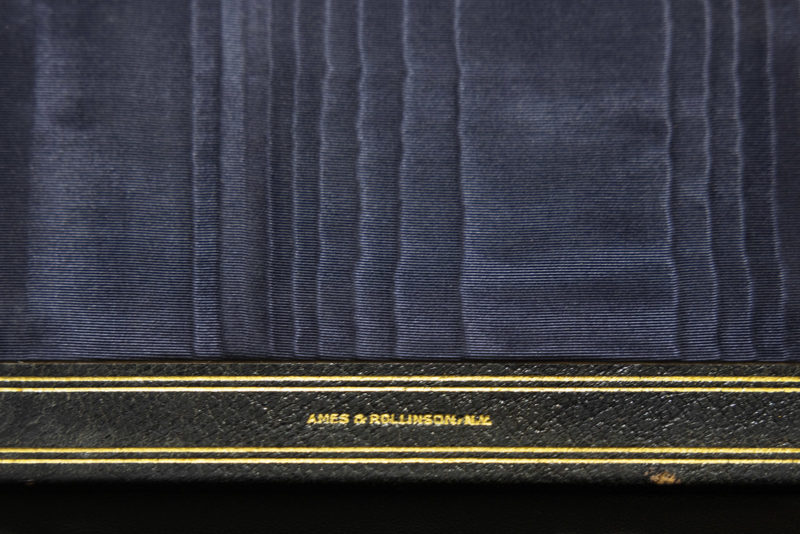

In New York City, the firm of Ames & Rollinson was noted for their work in the field. Around the 1930s, hand illuminated diplomas were their bread and butter—twenty-five artisans churned out over 10,000 diplomas each year, most of which were printed on traditional calfskin vellum. The company also produced many other unique and special documents, including the $25,000 prize check given to Charles Lindbergh from Raymond Orteig’s New York to France non-stop flight challenge, award certificates given to American Telephone & Telegraph Company employees that showed devotion by sticking to their posts during fires, floods, or gun battles, and an array of bound folders commemorating business executives upon their deaths.

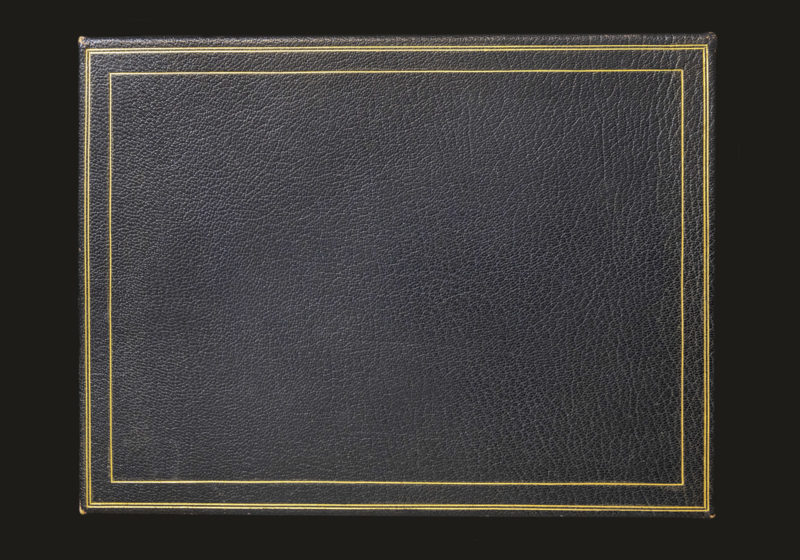

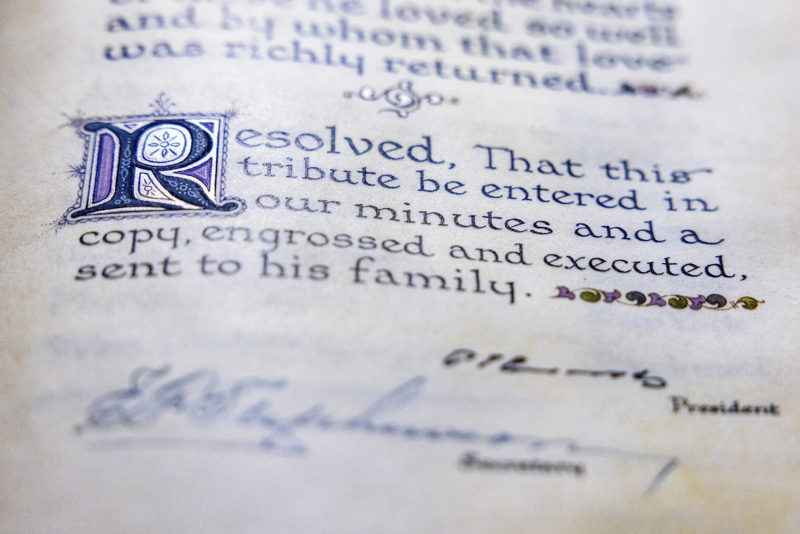

In lieu of any established name for said documents, I began referring to them in my mind as “death notes.” Typically, when an executive, president, or board member of a prominent company passed away, the board of said company recognized their efforts and achievements in the minutes of their next meeting. The transcript for that portion of the meeting was then sent to the artisans over at Ames & Rollinson, who produced an illuminated and bound copy to be presented to the next of kin. No expense was spared for these commemorative folders—they were bound in the traditional Moroccan style with a gilt tooled and dyed goatskin cover, a watered silk doublure, sheep or calfskin pages, and illuminated with either Italian gold or French platinum leaf. The resulting book would then be signed by a representative of the company before being sent off to usually the deceased executive’s wife.

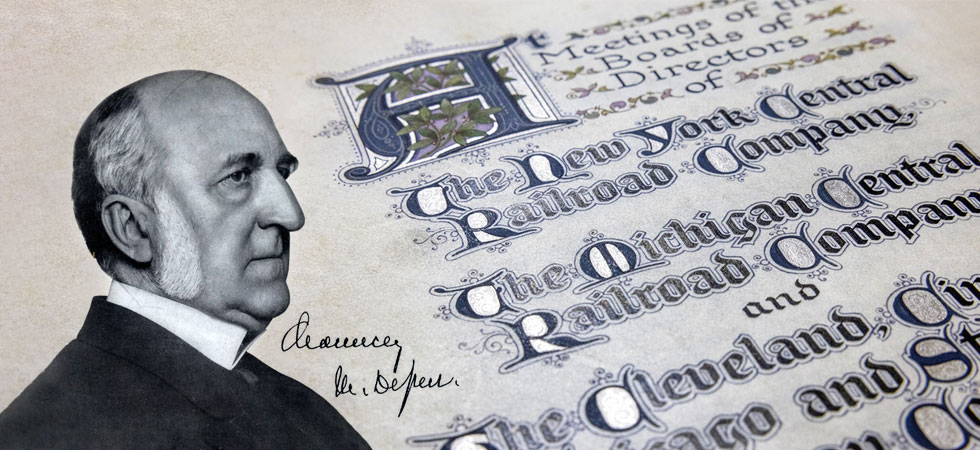

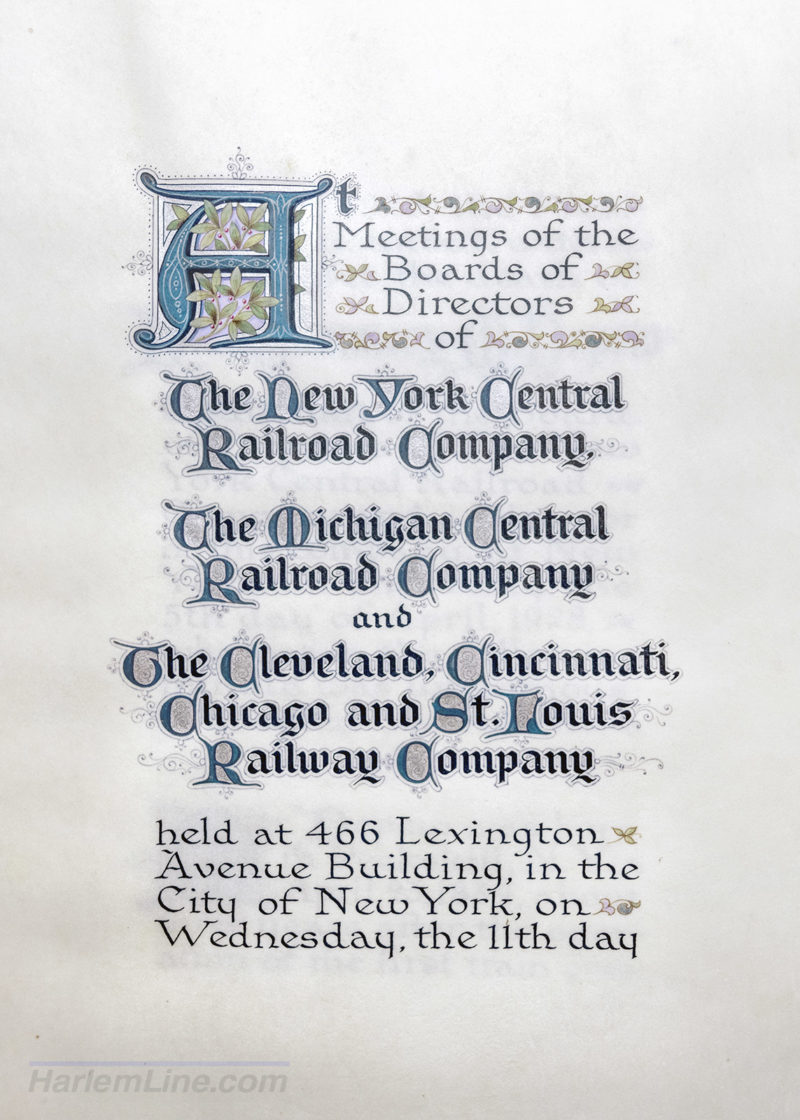

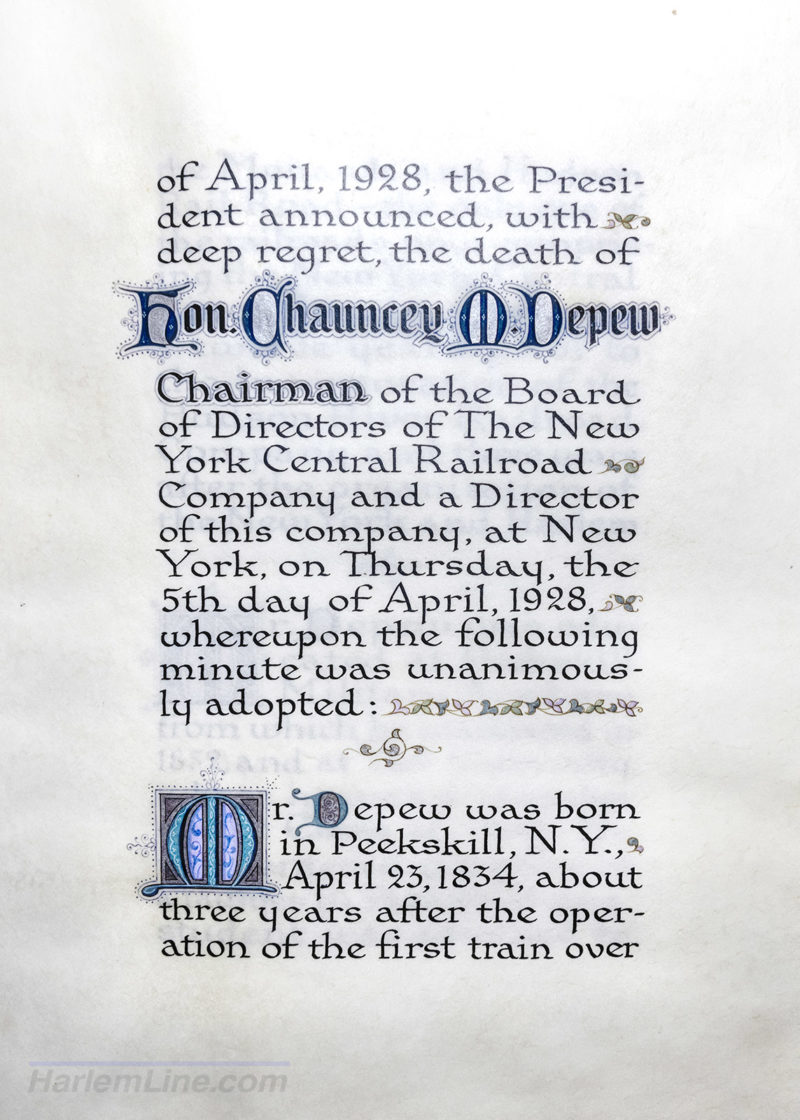

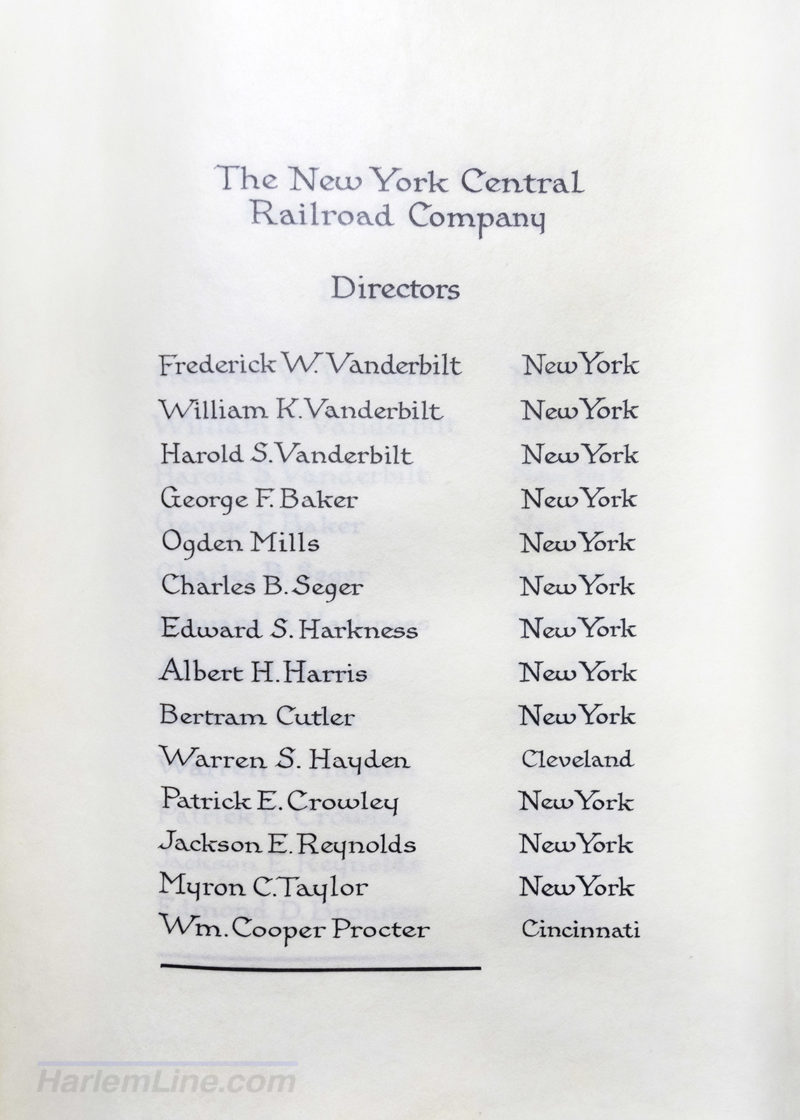

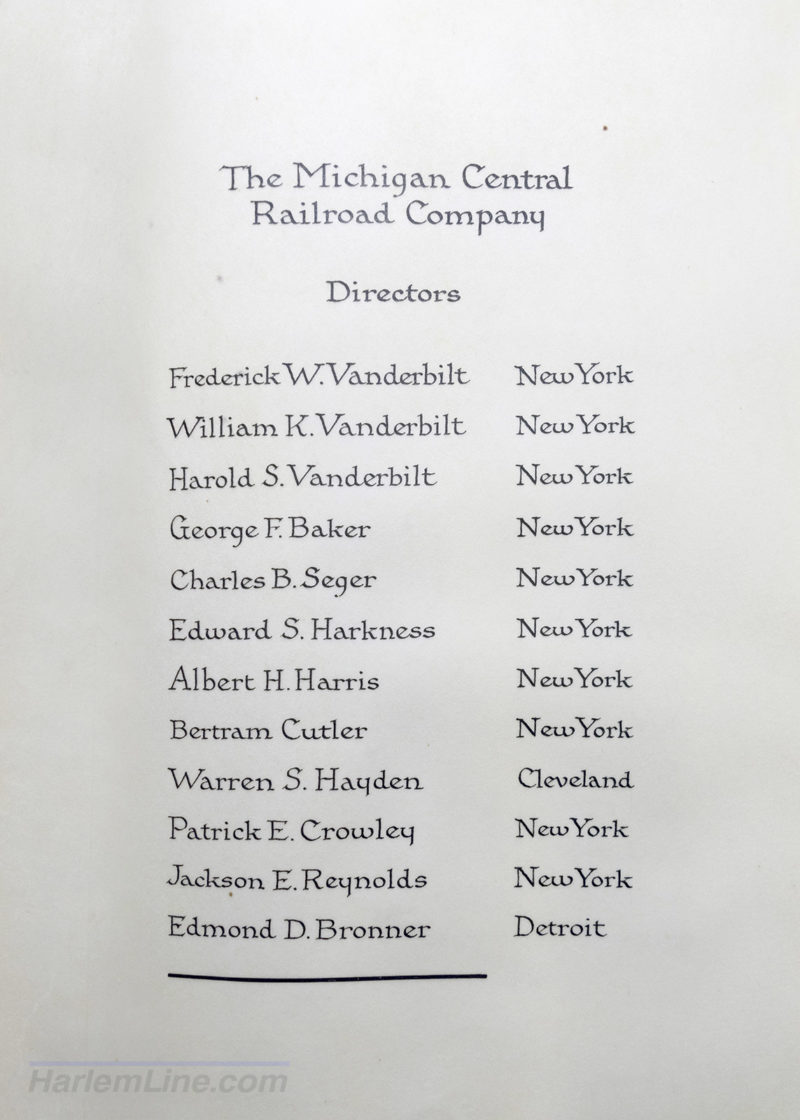

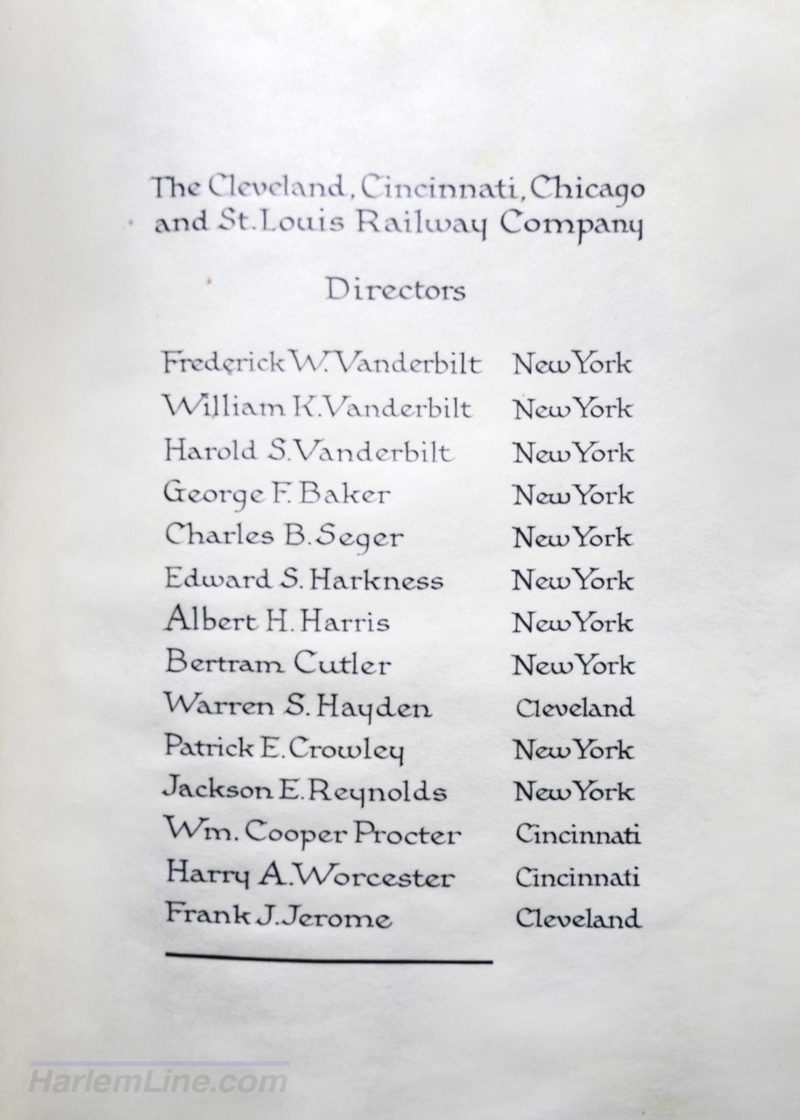

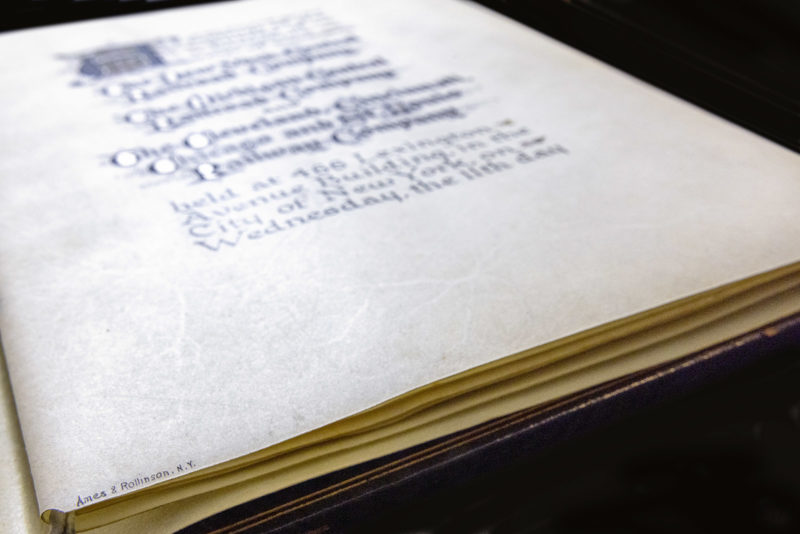

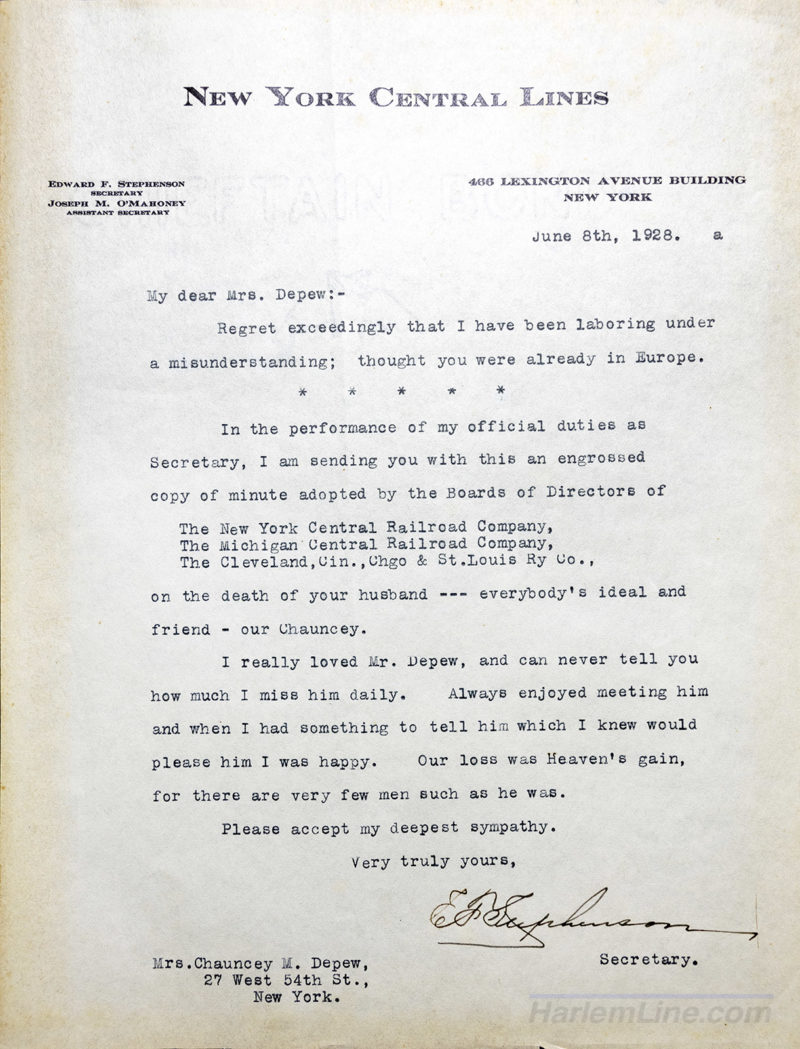

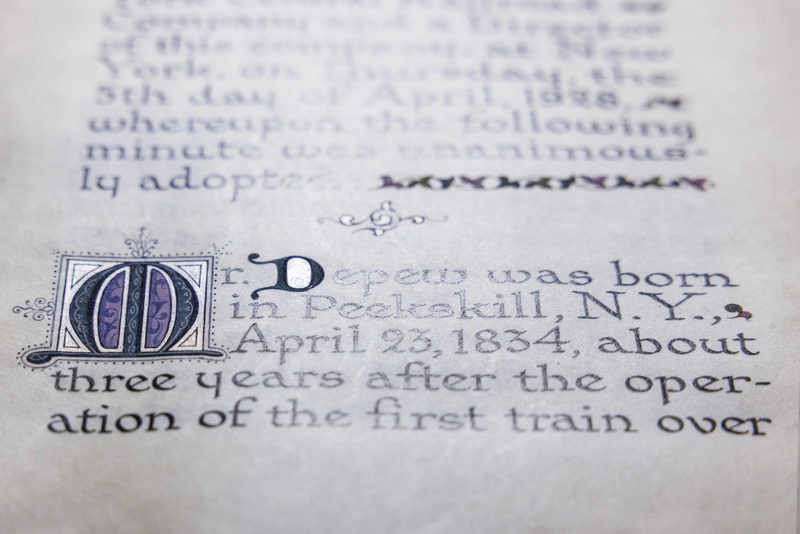

Ames & Rollinson created documents like these for a wide array of notable names, including Henry Morton Stanley, J. Pierpont Morgan, William Tecumseh Sherman, Walter P. Chrysler, George Pullman, and Chauncey Depew… whose original “death note” recently came into my possession. Commissioned by the New York Central Railroad Company, the Michigan Central Railroad Company, and the Cleveland, Cincinnati, Chicago, and St. Louis Railway Company, the ten page document provides a brief biography of Depew, along with a heartfelt tribute, and a listing of all of the board members for each of the railroad companies. Along with the folder is the original letter written by railroad secretary Edward Stephenson to Depew’s widow May Eugenie Palmer when the book was mailed to her.

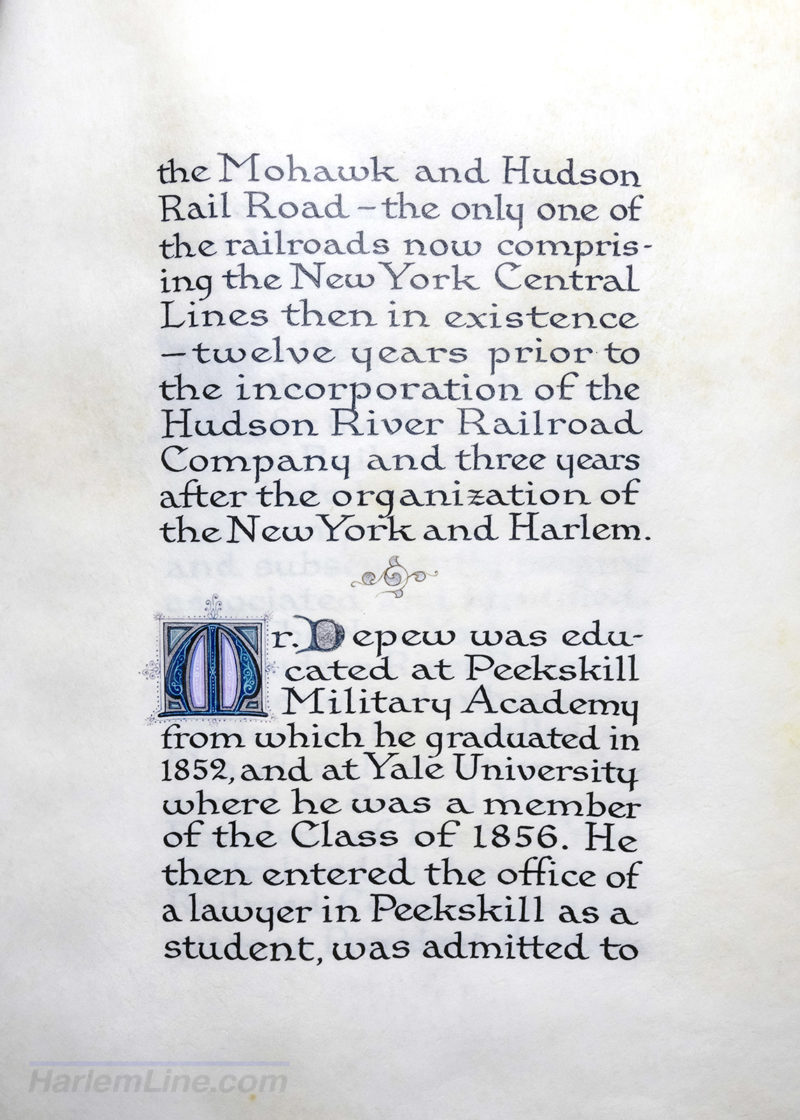

Born in Peekskill on April 3, 1824, Depew was a graduate of Peekskill Military Academy and Yale University. Admitted to the New York State bar in 1858, Depew operated a law practice in Peekskill. Around the time that Cornelius Vanderbilt came calling to offer him the position as attorney for the New York & Harlem Railroad, Depew had already been offered the position of US Minister to Japan. According to lore, when Depew told Vanderbilt about how the resident minister position offered better compensation, the brusque Vanderbilt retorted, “Railroads are the career for a young man; there is nothing in politics. Don’t be a damned fool.” And that is how Robert B. Van Valkenburgh became the US Minister to Japan, and Chauncey Depew became a railroad man.

When Depew started at the Harlem in 1866, Vanderbilt’s railroad holdings consisted of only around two hundred and fifty miles of territory. Ultimately, Depew would end up overseeing a massive railroad system of over twenty thousand miles as President and Chairman of the Board of the New York Central Lines. Depew’s legacy has been commemorated in the village of Depew in Erie County (where today you’ll find Amtrak’s station for Buffalo), several streets including Depew Place outside Grand Central and Depew Street along the Harlem in Pleasantville, and in a unique old manuscript, which I share with you today.

Beautiful and fascinating. I never knew any of this. Thank you for “illuminating” us all. :-)