As a photographer, explorer, and now-New Yorker I’ve found myself curiously drawn to the work of Angelo Rizzuto. Anthony Angel, as he called himself, was a street photographer who captured the city from the late 1940s until his death in 1967. His body of work was largely overlooked by the fine art world, seen more as snapshots from a madman with a camera than any sort of photographic art. Yet from a historical perspective, the images resonated with me.

Angel created a nearly 60,000 image strong visual time capsule of New York City—his photos of the old Pennsylvania Station, of Mott Haven yard, and of the dismantling of the elevated structures carrying subways over Manhattan show how things used to be. I am intrigued by the little details of streetscapes and of people waiting for trains, and wonder how he reached some of his lofty vantage points—he must surely have managed the cupola of the New York Central Building to capture the top of Grand Central before the Pan Am building was constructed, and scaled public housing projects in Marble Hill to photograph the old station there.

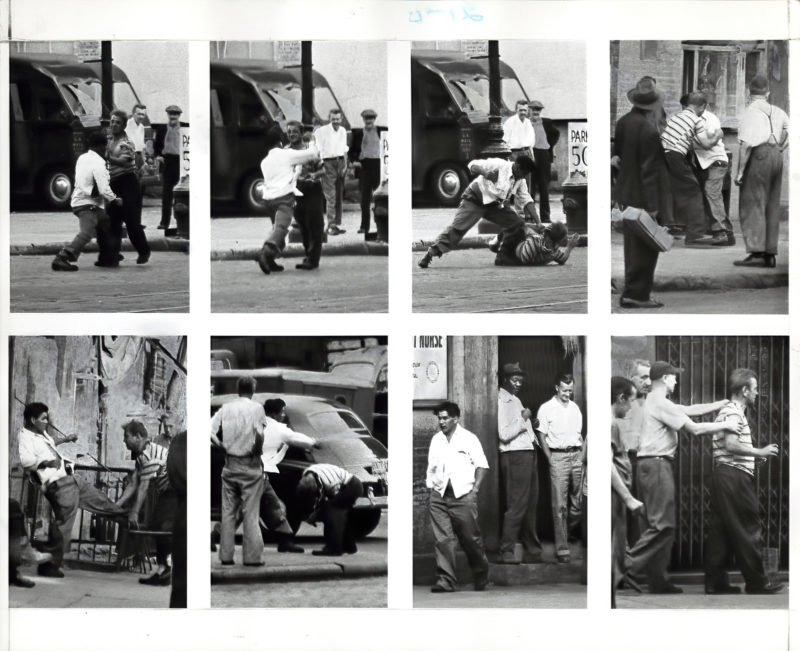

Angel also seemed captivated by humans in unsuspecting or even vulnerable positions, and there were times that I, as the viewer, was slightly distraught in gazing upon the voyeuristic images, moments that perhaps should never have been captured at all. From men gazing through peepholes at live nude shows, passed out individuals being unceremoniously hefted into paddywagons, or women tearfully attempting to hide from the world, Angel captures an underbelly of New York that I am unaccustomed to seeing.

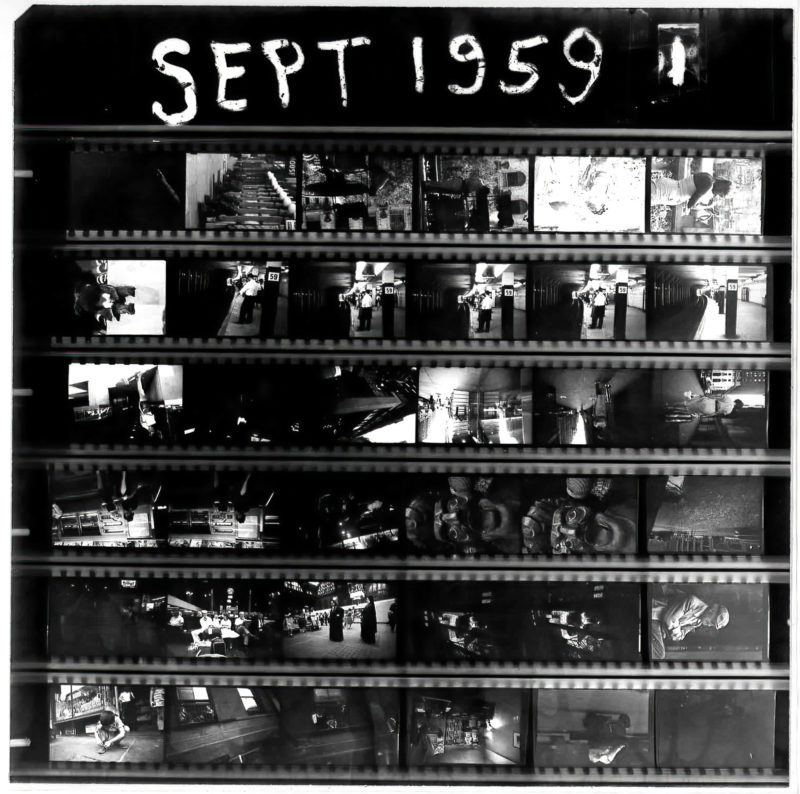

A contact sheet of photographs from September 1959. Photos include the 59th Street subway and Pennsylvania Station.

That dark line of thought becomes even murkier when one learns more about the man himself. It is hard to deny that Anthony Angel, although clearly an intelligent and talented individual, suffered from mental illness. Institutionalized for a suicide attempt and later discharged from the army for medical reasons, Angel was found by both to suffer from delusions (“dementia praecox, paranoid type” may have been diagnosed today as schizophrenia). He was ritualistic—only venturing out from his apartment at 2 PM every day to capture his photos, later returning to process film and haphazardly generate contact sheets. Despite his obsession with chronological organization, the finer details—removing the dust and hair from the negatives, or even making sure they were not backwards or upside down, were lacking. When he wasn’t out photographing, Angel was creating patent applications for commercially useless inventions, or writing hateful, often antisemitic, letters to governors, senators, supreme court judges, and even the FBI. He believed that the communists, perverts, corrupt judges, or whatever demon du jour was out to get him—paranoid delusions fully on display.

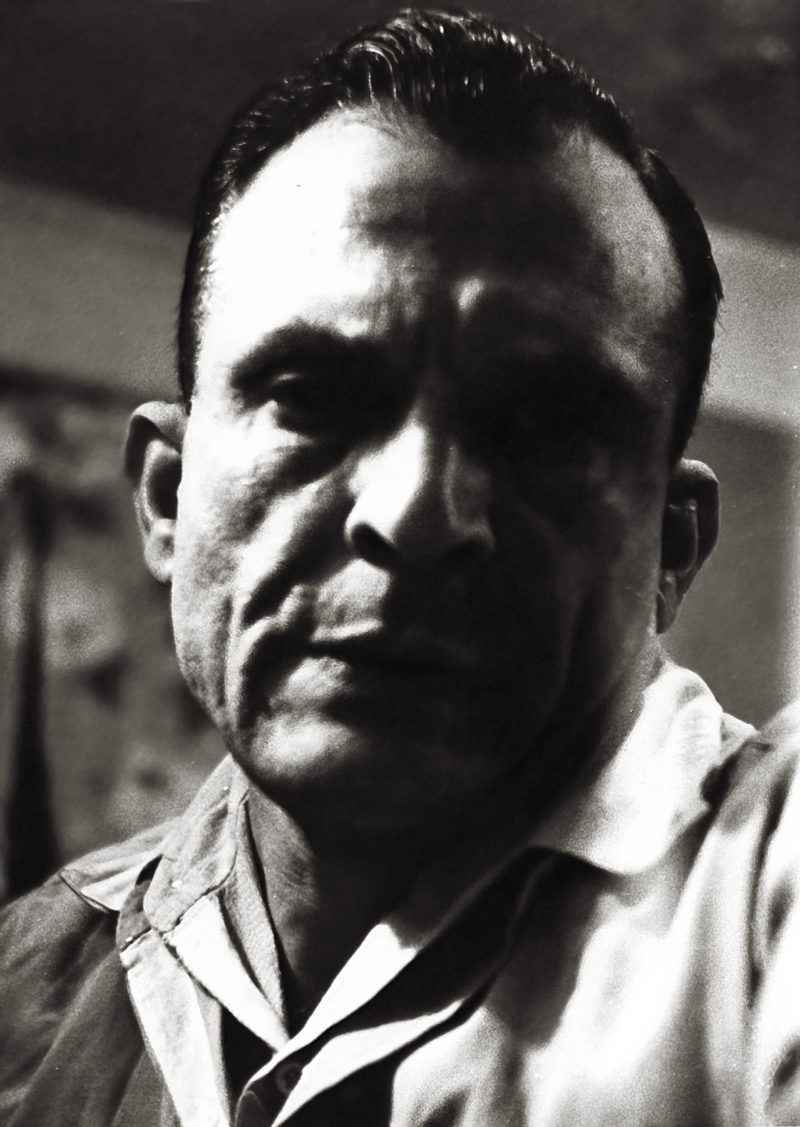

Although photography may have been an outlet for these delusions, Angel’s work reflected his often neurotic mindset. His surreptitious captures of women and of people from afar mark him as an awkward outsider, a recluse unwilling or simply unable to genuinely interact with others, yet inserting himself into their sometimes private moments. His comic-strip-style printed sheets of image sequences seem more cinematic than photographic, with Angel playing the scene director, completely detached from the mayhem of the street fight in front of him. Even his array of self portraits, often captured at the end of each roll of film, reflect the inner turmoil of his psyche—alternating between goofy to serious to pained and even enraged.

Self portraits of Angelo Rizzuto, aka Anthony Angel

Despite the problematic nature of the individual, Angel’s captures are undeniably valuable for those wanting a glimpse of New York nearly seventy years ago, especially the railroading infrastructure that appeared in so many photos. But what exactly was it that drew him to these places? Were his visits to Grand Central and wanderings along Park Avenue simply a byproduct of living in close proximity? Was it only fortuity that Angel’s paranoid letter writing spree coincided with the final years of Pennsylvania Station, which he stopped to photograph while on the way to his post box across the street? Or was there some genuine interest in the subject matter—a recollection of his youth where his father served as a construction contractor for the Union Pacific railroad? Beyond his stated intentions to publish a modern day sequel to Stokes’ Iconography of Manhattan Island, any further insight into his motivations or artistic intention were taken to his grave.

A small fraction of Angel’s work has been digitized by the Library of Congress and can be previewed online. Much of the credit for this work coming to light belongs to Michael Lesy, who encountered the images at the LOC decades ago and compiled the majority of the information we know today about Angelo Rizzuto.

Special thanks to Barbara Orbach Natanson and Jan Grenci at LOC’s Prints and Photographs Division, who were kind enough to share some of the contact sheets from the collection as I hunted from railroad images not yet digitized.

Are we sure “men at peep show – 1949” aren’t just looking at some construction going on behind that fence?

Fascinating post, Emily, thank you. Happy new year!