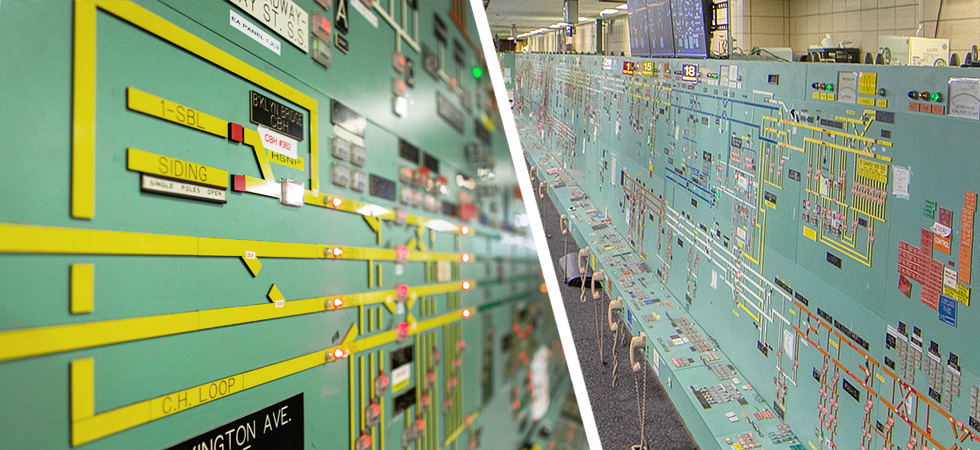

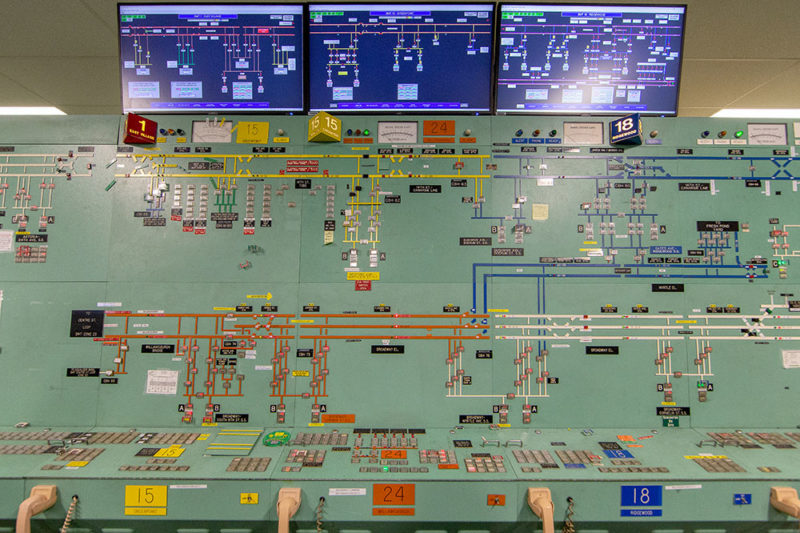

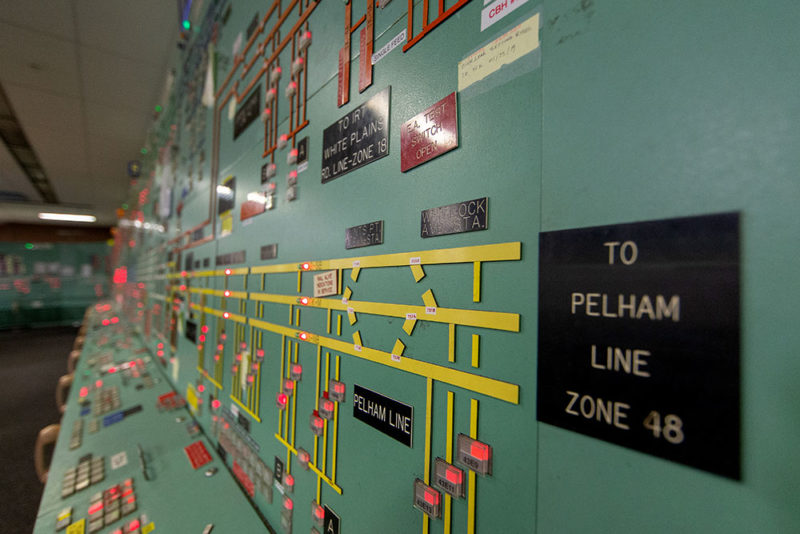

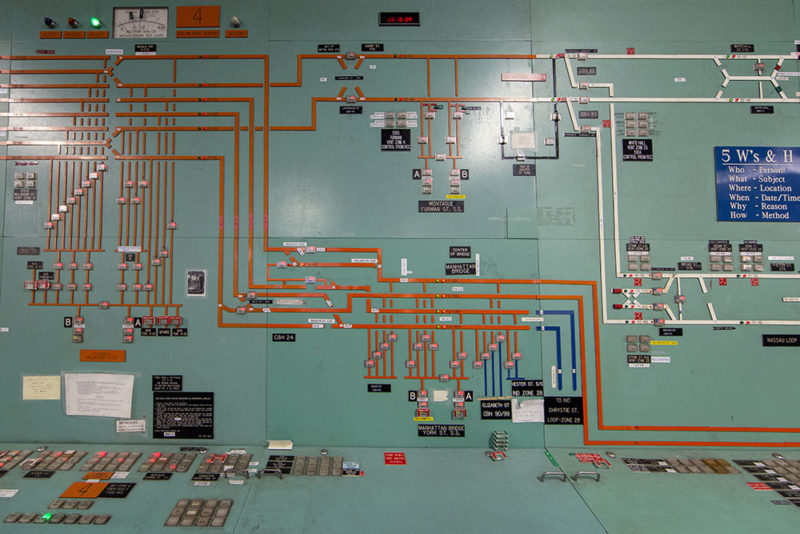

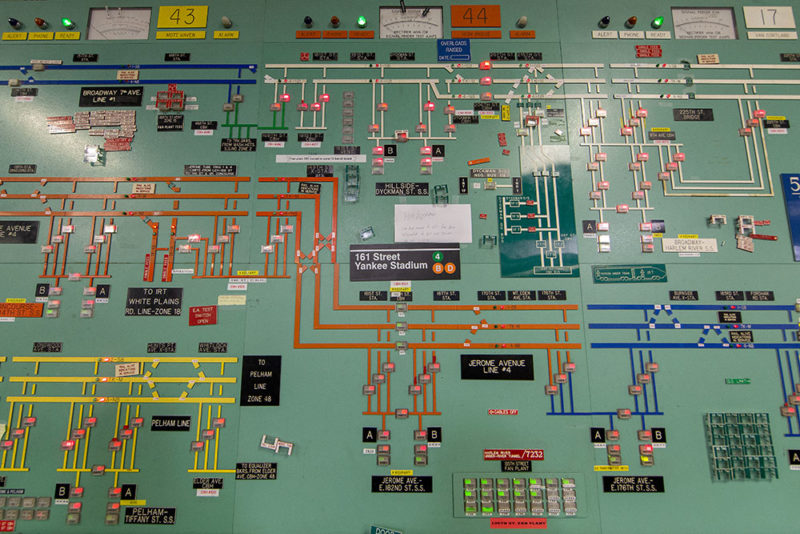

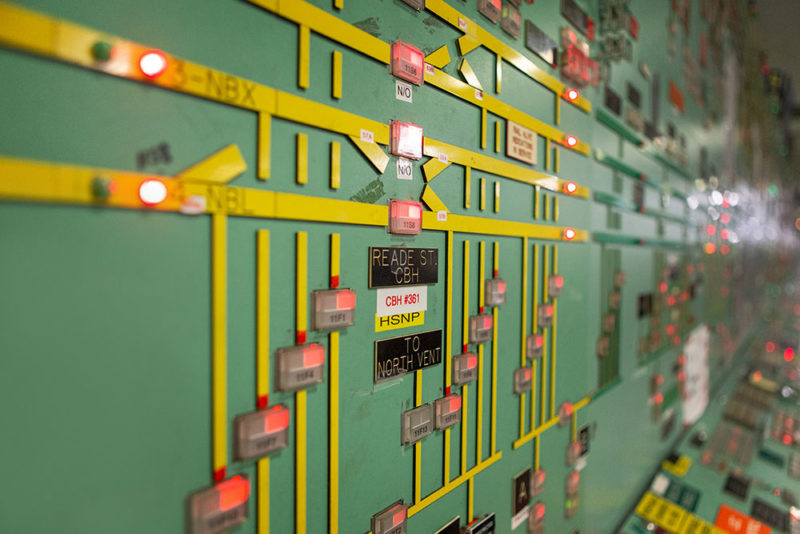

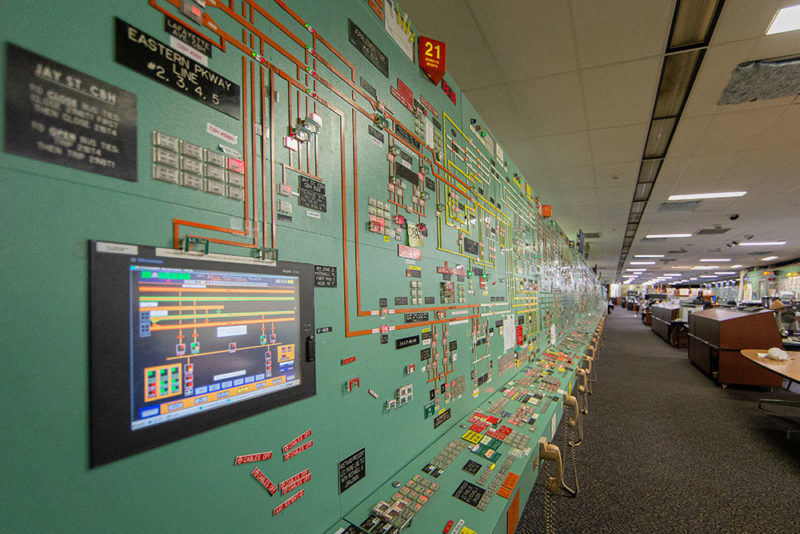

Throughout the city there are countless nondescript structures that garner little attention from passersby. Hidden within one of them is the Power Control Center of New York City’s subway system, which like many important pieces of infrastructure today tries to keep a lower profile. A venerable hive of activity, the Power Control Center occupies an enormous room with long rows of seafoam green control panels running its length. Clusters of desks are arranged in the middle between the panels, with a perfect sight line to monitor the flashing lights and relayed information. The PCC’s expansive control panels display a schematic of all of the subway’s lines, tracks, stations, substations, fan plants, circuit breaker houses, and other important pieces of the power system.

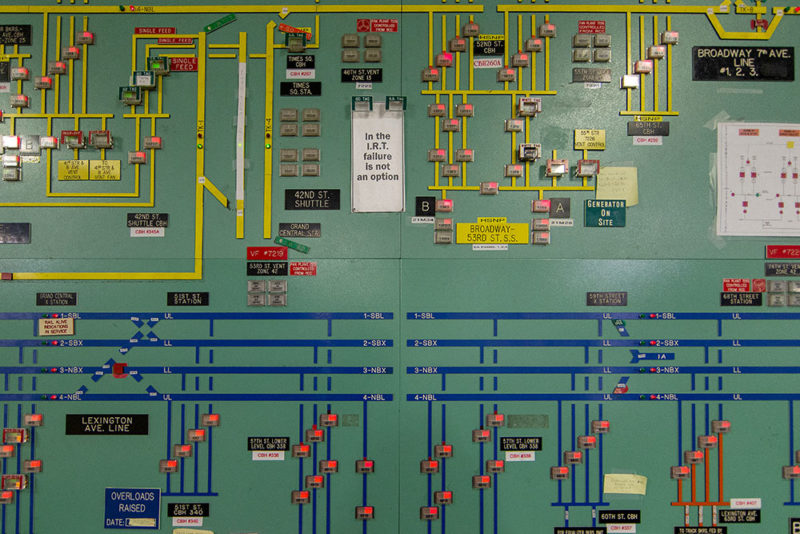

The Power Control Center oversees the operation of over 218 substations dispersed throughout the city. Information from these locations is relayed to the panels, giving operators the ability to see what’s going on and to control the subway’s power from a centralized location. For unexpected changes or ongoing situations, such as police presence, an array of magnets can be placed upon the board to keep everyone apprised (if there was a special cat-faced magnet for de-energizing the tracks for a feline rescue, I did not see it). Hidden within the collection of tracks and magnets are other tidbits, including the message, “in the I.R.T. failure is not an option”—assumedly a more down-to-Earth play on the fictional words uttered by the heroic operators employed in another green hued control room.

If you get a retro nuclear control room vibe from the seafoam green panels, that’s not surprising. Many control rooms—from the bridge of the Queen Mary 2 to the nerve centers of nuclear power plants around the globe—use a similar color scheme. Earlier subway control panels used white lines atop a black background, similar to the model boards found in old towers, but were upgraded to these green colored panels in the early ’80s. Design tastes and prevailing science often shift, and at the time such installations were considered optimal for readability, preventing eye fatigue and reducing glare. For nuclear applications dark colored backgrounds on Human-System Interfaces remain inadvisable (though a light gray seems to be the popular choice over dated seafoam today), but many railroads still use negative polarity color schemes in their control centers, and such “dark mode” schemes are popular with consumers. Ultimately, the best solution for readability depends heavily on ambient light, which is probably why Amtrak’s CETC dispatchers have long used black background interfaces in dark rooms.

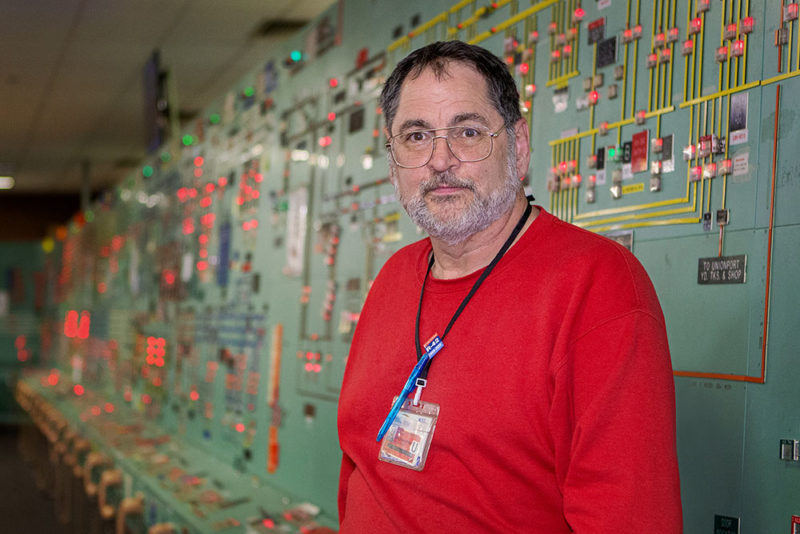

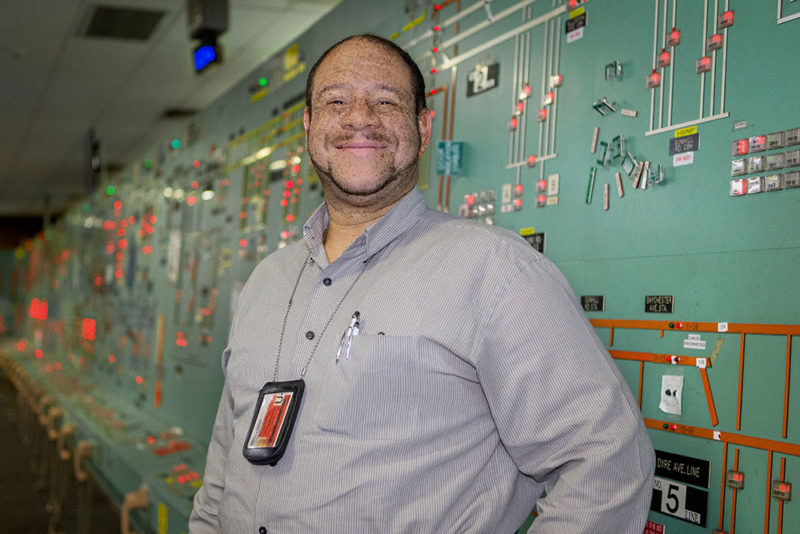

In the collection of photos I snapped while at the Power Control Center you’ll note that Loby makes a reappearance, in red and looking very serious, along with a much happier photo of Eric, who works in the PCC. Sometimes it is pretty easy to tell when someone really enjoys their work, and Eric says that he is very proud of the job done by all at the Power Control Center. With over 665 miles of mainline track and 472 stations, the employees of the PCC certainly bear a large responsibility to keep the lights shining and the trains running on a subway system that uses more power than the state of Vermont.