Milk has long been a staple of the American diet, and since the New York and Harlem Railroad was founded up until the 1950s, it was also a staple commodity carried by rail. Early in New York City’s history, dairy cows were kept and milked in the city proper near distilleries. Often sick cows were kept in cramped conditions, and fed the byproducts of whiskey making – resulting in a blue tinted “milk” that was lacking in cream content and dangerous to drink. Unscrupulous businessmen used additives – including water, sugar, molasses, egg, and even plaster of paris – to give it the appearance of fresh milk and sell it to an unwitting public. This tainted milk led to an increased infant mortality in the city, and was coined the “Swill Milk Scandal” when exposed in the periodicals of the day. The scandal eventually led to regulation of the milk industry, and a push for “pure milk” from dairies far outside the city. Stepping up to transport this milk were, of course, the railroads.

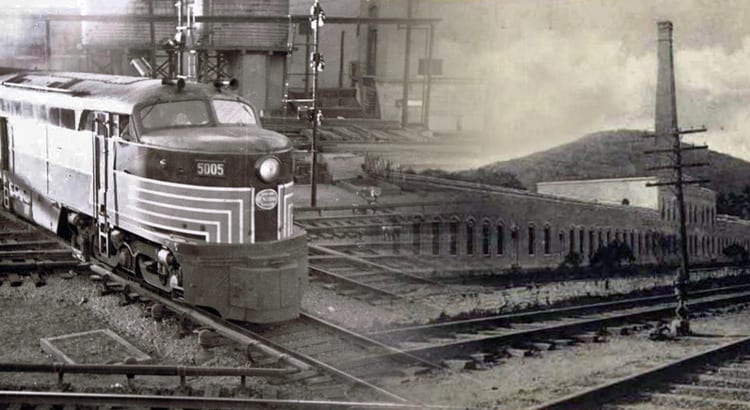

The famous “Rut Milk” train passes through Mott Haven in the 1950s. The milk trains were eventually replaced by trucks. Photo by Victor Zollinsky.

Milk depots were established at many train depots, and local farmers could bring and sell their milk, which was then transported to the city. One of the Harlem’s most famous freights was the Rutland Milk train, which brought milk to New York City from Vermont – transferring from the Rutland Railroad to the Harlem in Chatham. Every day a swap would occur where a train full of milk changed hands at Chatham, exchanged for the previous day’s empties.

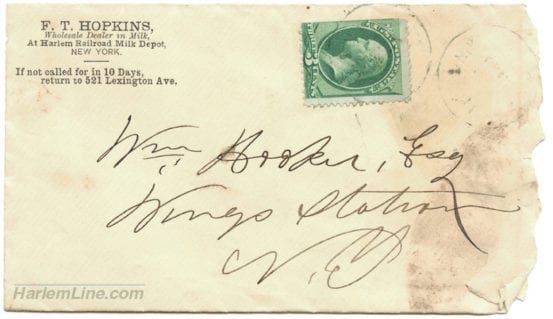

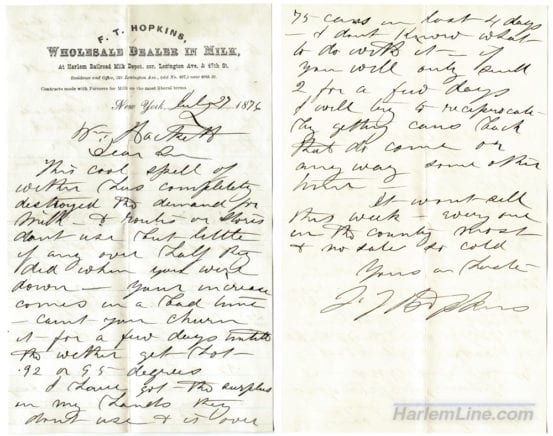

Today’s random tidbit from the archive is a letter from F.T. Hopkins to William Hooker. Hopkins was a milk dealer who operated the Harlem Railroad Milk Depot in New York City. The letter is addressed to Hooker at Wing’s Station – an earlier name for Wingdale.

Borden on the Harlem Line

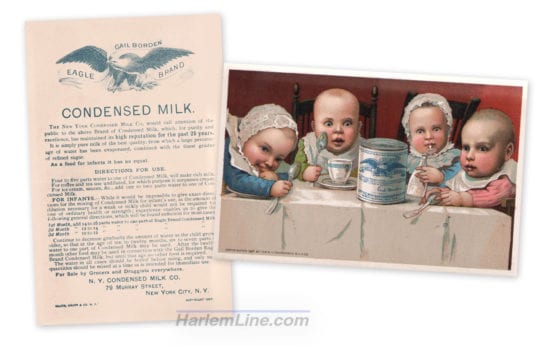

New York Condensed Milk Company / Eagle Brand condensed milk promotional card.

Even if the milk transported by train to the city was considered “pure” and not of the “swill” variety, it did not last very long before spoilage in the days prior to refrigeration. Condensed milk stored in cans, however, could last for years without spoiling. Not only was condensed milk transported along the Harlem, it got its start here.

There are many ways to describe Gail Borden Jr.: a perpetual wanderer, deeply religious (anecdotal evidence suggests that he bought bibles for placement on the Harlem’s trains), eccentric inventor (he scared his friends by taking them on a ride straight into a river in a self-invented amphibious wagon – the “terraqueous machine”), an endlessly stubborn optimist that never gave up. All of those traits led him from his birthplace of Norwich, New York to Kentucky, Indiana, Mississippi, Texas, Connecticut, and ultimately back to New York and the Harlem Railroad to launch his most successful invention – condensed milk.

For some time Borden had been interested in preventing food from spoilage. One of his first food related inventions was a meat biscuit, made from rendered meat and flour or potato and baked into a cracker, which could be eaten as is, or crushed into boiling water to make soup. He also experimented with preserving and concentrating fruit to make juices, and making coffee extract which took up far less space than regular coffee. Despite winning prizes for the meat biscuit, none of those endeavors were commercial successes. After debts forced him to give up on the meat biscuit and sell some of his property to pay creditors, Borden wholeheartedly pursued his milk preservation idea in Connecticut – starting a factory in Wolcottville. He eventually ran out of money and that factory closed, later replaced by a different factory in Burrville. Unfortunately, the Financial Panic of 1857 marked the end of that venture as well.

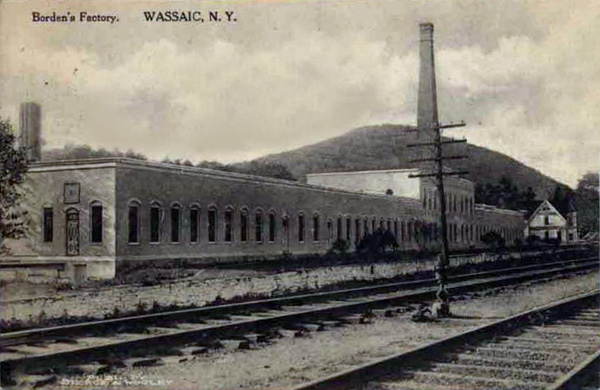

The first successful condensed milk factory, Wassaic, New York

The original Borden factory today, now occupied by the Pawling Corporation, which manufactures architectural products.

A chance encounter on a train ride, however, brought Gail Borden and financer Jeremiah Milbank together, and Milbank found promise in Borden’s idea. With Milbank’s money, Borden founded the New York Condensed Milk Company in Wassaic, New York, right next the the tracks of the Harlem Railroad. Borden’s tenacious spirit had finally paid off this time around, as his product became a commercial success. Another factory was constructed along the Harlem in Brewster to keep up with demand – and condensed milk became a staple for members of the Union Army during the Civil War.

After Borden’s successes he moved back to Texas, but upon death was returned by train to New York. He forever remains next to the Harlem Line, buried in Woodlawn Cemetery with a large monument that bears the following quote:

“I tried and failed. I tried again and again and succeeded.”

These stories are great. My grandfather was a conductor on the Harlem Div (he lived in Chatham). He passed when I was young. As old newspapers are scanned and made searchable on the web, I’ve learned more about his railroading, as he occasionally shows up in stories about the railroad.

Good info and interesting.

Thanks

F. T. Hopkins, IV lives nearby the Harlem Line in Southeast. He’s my Brother-in-Law. After F. T. Hopkins, II was born, the family moved to Somers. Their home is Muscoot Farm, now a Westchester County park.

My wife and I live in the Sheffield Farm house in Pawling. The milk plant in the village of Pawling was associated with Sheffield Farms. The farm had its own siding on the Harlem Line. The end bumper is still visible at the Appalachian Trail parking area on the east side of Route 22.

Is it possible to visit the Borden’s and Sheffield sites? I write about them in my history of milk, Nature’s Perfect Food, but have not seen these places. I didn’t know they still exist!