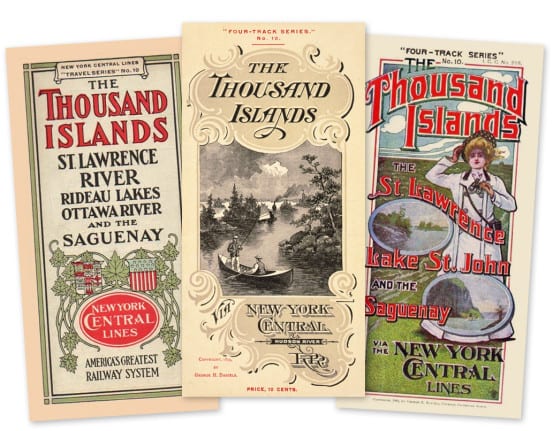

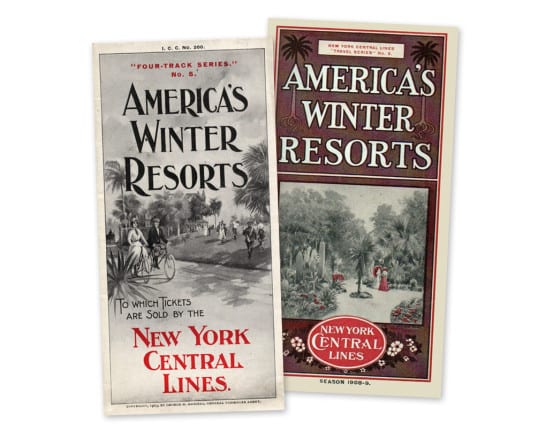

Much of Daniels’ promoting came down to a persistent tagline – “Send a stamp to George H. Daniels.” Any soul that would send off a letter to the man in Grand Central, and enclosing a two-cent stamp – of any country, in fact – would be returned travel-related literature pertaining to their specific interests. Perhaps a businessman would get a map of global trade lines, undoubtedly featuring the fine rails of the New York Central and its connections stretching across the United States. A science-minded fellow would find descriptions and diagrams of mighty steam locomotives in use by the railroad, or the newest technology found in use on the road. And a sportsman might find a guide to fishing in upstate New York, complete with photos of the varied fish found within each body of water. Daniels and his team created a litany of brochures for just about any interest, railroad or not. For the more philosophical, there was the reprint of Elbert Hubbard’s “A Message to Garcia” – of no relation to the railroad, yet complete with a map of the line as a reference point. Certainly one of his most prolific publications, it can only be argued that after being printed by the railroad the story went “viral” – and Daniels promised to print as many copies of it as were desired, even if it took a century to do so. The story was subsequently made into two different motion pictures, sold over 40 million copies, and was translated into 37 languages, largely due to Daniels’ influence.

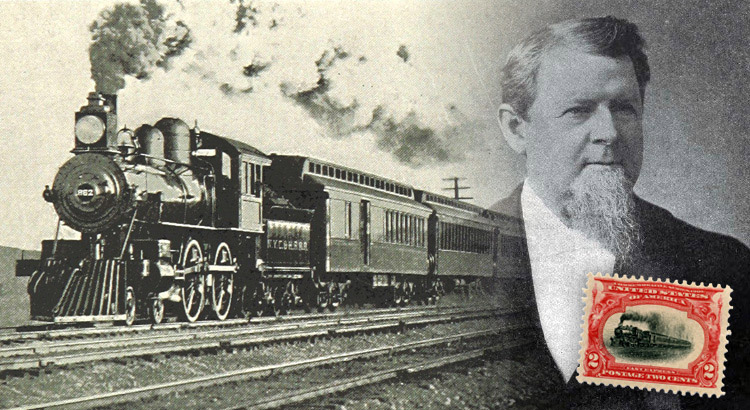

One of the early publications by Daniels for the Chicago & Pacific, and his photo from 1889

Born in 1842, George Henry Daniels grew up on the farms of Hampshire, Illinois, not far from the border with the territories of Wisconsin and Iowa. Daniels landed his first railroad job at the age of fifteen for the Northern Missouri Railroad, one year before that road completed its main line from St. Louis to Coatsville. Fifteen years later when that road fell into financial difficulty, Daniels made the jump to the Chicago & Pacific Railroad, as a general freight and passenger agent, landing an office in Chicago. In between those years, however, Daniels’ labor of love was contributing local news to a newspaper in Chicago. He continued his writing while in the employ of the Chicago & Pacific, using it to promote the railroad. He published a historical account of the road in 1873. He spent eight years at the Chicago & Pacific, before returning his previous railroad company, which had by then been absorbed into the Wabash, St. Louis and Pacific.

Daniels later moved on to hold positions as the commissioner of the Iowa Trunk Line Association, and further out on the frontier as the commissioner of the Colorado Traffic Association not long after that territory was granted statehood, and the Utah Traffic Association when it was still a mere territory. By 1886 hw had become the commissioner of the Central Passenger Committee, which later became the Central Traffic Association, of which he was elected vice-chairman. He then rose to the chairmanship of the Chicago Eastbound Passenger Committee, which attracted the interest of the New York Central, who offered him a position as the General Passenger Agent of the railroad in New York City.

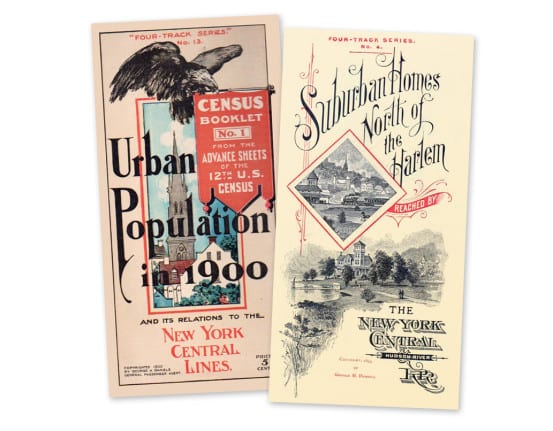

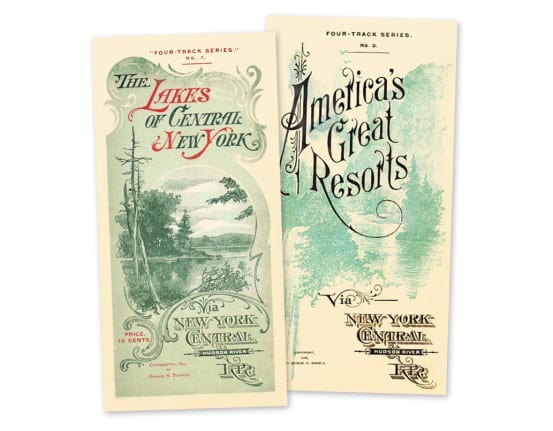

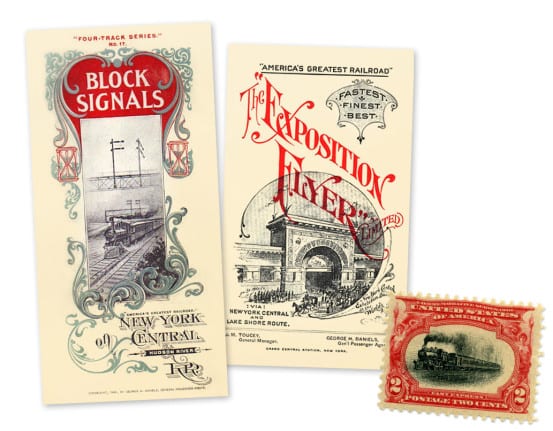

Brochures published by Daniels during his tenure as General Passenger Agent, and the special stamp featuring the Empire State Express

Though one could hardly imagine that a single man out of an office in New York could effect the prunes of California, the apples of Oregon, or the mail from Australia, Daniels’ influence was both far and wide. Commanding both the trains of the Central and the power to spread a news story, Daniels served up prunes and apples – carrying them by freight to the east coast in conjunction with the Southern Pacific, having them served in all train dining cars, and promoting their superiority in the news. As for Australia’s mail, how exactly did a letter mailed from Australia, bound for London actually arrive in the year 1899? Using the Central’s trains to set a record, mail traveled by ship to the west coast, was transported by train to the east coast, and then sent yet again by boat to its final destination – a grand total of 32 days. In instances like these Daniels felt he was not only a promoter of the railroad, but of the entire country of the United States – showing the world the mighty steam trains and other products of American ingenuity.

Harlem Division timetables that bear the name George H. Daniels

Pull any timetable from the era printed for the New York Central, and on the bottom you’ll likely find Daniels’ name. In addition to the brochures he printed touting travel destinations, Daniels launched a full blown travel magazines from Grand Central Station, naming it the “Four-Track News” (the Central’s moniker at the time, the “Four Track System,” was coined by Daniels, highlighting its history as the world’s first four tracked railroad). That magazine operated in some capacity until 2003, under the names Travel and Travel Holiday. He also coined the name “Empire State Express” in 1890, and was tasked with promoting the Central’s newest train that made the trip from New York to Buffalo in just over six hours, making it the fastest scheduled passenger train in North America. Later on, he further promoted the Empire State Express with the locomotive 999’s 112.5 MPH speed test, specifically targeted to get people’s interest on the Central in time for The Chicago World’s Fair in 1893, where the record-breaking locomotive was placed on display. Daniels even managed to get the US Postal Service to print a commemorative stamp featuring the locomotive, one the first stamps printed in the 20th century. Arguably, however, Daniels’ most notable achievement was the concept and launch of the “20th Century Limited” – the New York Central’s most famous train.

Retiring from his position as General Passenger Agent in 1905, Daniels became the director of the New York Central’s new advertising department. He served in that capacity until 1907, when he retired permanently, living his final year split between Buffalo and Lake Placid, before passing away in 1908.

Note: Wikipedia and other sources claim that Daniels was at one time a patent medicine salesman, or that he once worked on steam boats, however his contemporary biographies, and various obituaries make no mention of this. The only sources I can find for this claim were newspaper articles written more than 50 years after Daniels’ death, of which I am interpreting as erroneous.

A collection of brochures published by Daniels during his tenure as General Passenger Agent