Reading all about the history of the Harlem Line intrigues me. It was New York City’s first railroad, chartered in 1831, and an early example of a rail horsecar in the United States. As in every story, there are always intriguing characters. People like Cornelius Vanderbilt certainly stand out. But for me I think one rarely mentioned woman stands out the most. Her name is Lettie Carson, and she fought to prevent the closure of the Upper Harlem, a David against Penn Central’s Goliath. As we all know that the Harlem does not extend to Chatham anymore, unfortunately her plight failed, but her story still captivates me.

Lettie Gay was born in Pike County, Illinois in 1901, the youngest of nine children. On the family farm she helped raised livestock of every variety. It may be this upbringing that gave Carson her independent attitude. At age eight she would drive a horse and buggy fifteen miles to the train station to pick up her brother. In the early 1920’s she moved east to the New York area, and in 1924 married Gerald Carson. She held various jobs, including as food editor of Parents’ Magazine. She and her husband had a weekend home in Millerton, along the Harlem Line, which they retired to and became permanent residents in 1951.

If you’re on the north end of the Harlem Line you may be aware of Lettie Carson’s work without knowing it. In 1958 she helped create the Mid-Hudson Library System, which today has more than 80 member libraries across five counties. Brewster, Dover Plains, Mahopac, Patterson, Pawling, Poughkeepsie, and Chatham are a few of the towns whose libraries are members. Carson served as president of the Mid-Hudson for two years, and was on the board for eight.

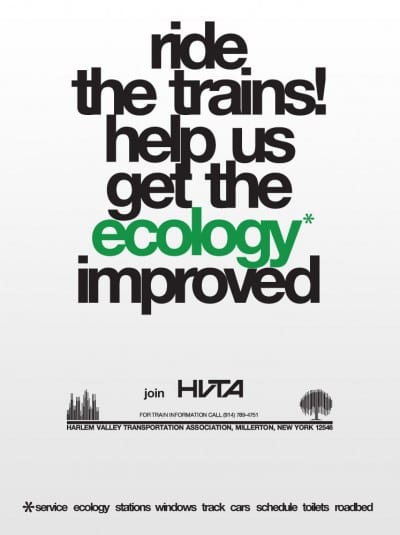

Lettie Gay Carson later became associated with the Harlem Valley Transportation Association, as vice president, and then as president. The organization was formed in the early 60’s when the New York Central threatened to abandon passenger service on the Upper Harlem. When Penn Central took over they too wanted to end passenger service north of Brewster. The HVTA fought them for many years through demonstrations, public hearings, and in the courts. Ultimately the passenger service was abandoned north of Dover Plains in March of 1972, though the HVTA continued to fight for freight on the line. Eventually that too was abandoned, and the track was ripped out.

Through my research I managed to unearth some of the HVTA’s old documents: papers, posters, surveys and more. I’ve digitally restored some of them for posterity. Below are four of the HVTA’s early posters, as well as their logo and letterhead.

Later in life Carson moved to Pennsylvania, where she too attempted to protect rail service in and around Philadelphia. She died in March of 1992, at age 91.

Thanks for a great story!

As much as I enjoy rail-trails (and I was biking on the one in my backyard just yesterday) I can’t help but think they’d be better utilized with trains running on them again. Maybe someday? In the meantime, get up here and enjoy the Walkway Over the Hudson. It’s featured in the new Ulster County Tourism video:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cYyoYM0CNwM

As for the Mid-Hudson Library System, its inter-library loan system is terrific. I request a book online, it’s delivered to my local library, and I get an e-mail notice telling me it’s ready for pick-up. Thanks Lettie!

Wow that is some tight spacing there on the posters.

An understatement! As much as I would have loved to fix that up, I kept it true to the original.

I just saw the “you may also like” reference to this post. At the risk of responding to a 15 year-old post, I’d like to mention…

Thanks for sharing this. Very interesting.

Ms. Carson was a remarkable person. I had the honor of meeting her during her work to improve Philadelphia area transportation. Really sharp and super nice. Didn’t hesitate to speak out.

It’s a shame they couldn’t save the upper Harlem Line to Chatham. I understand traffic congestion in the area is bad thanks to growth and the railroad would be useful today.

I don’t know if this is true, but I heard the Penn Central was so anxious to kill the line that as soon as they got court approval they immediately stopped service in the middle of the day. That meant commuters who took the train to work in the city had no way to get back home.